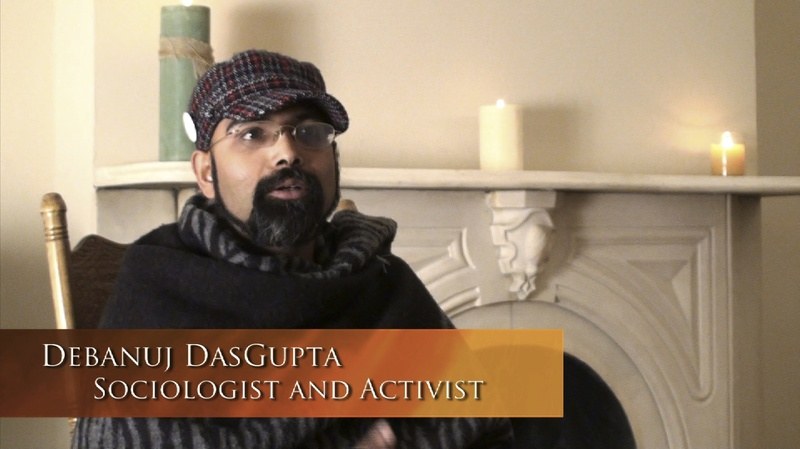

Debanuj DasGupta’s current activism and research travels take him through India, UK and the US focusing on issues of national security, migration, and embodied justice. A Doctoral Candidate in Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at The Ohio State University, Debanuj co-founded the first HIV and AIDS prevention project among men-who-have-sex-with-men and gay men in Kolkata in 1994. Debanuj has received several awards including the Association of American Geographers National Awards in Disability Studies, The Space, Sexuality, and Queer Research Group of the Royal Geographic Society/Institute of British Geographers International Travel Award, and has been one of the key members of the ‘Lift the Ban Coalition’ which effectively removed the HIV ban on travel and immigration to the US in 2010. He serves in advisory capacities for several philanthropic, research bodies, and policy formations.

TARSHI: Can you tell us a little about your work in immigration rights and how you got interested in this area of work?

Debanuj DasGupta: Thank you for thinking about my academic/activist work related to migrant justice. The issue of immigration, the ways immigration shape diaspora as well as families in countries of origin is personal. My parents’ families were uprooted from (now) Bangladesh during the partition of Bengal. The partition of Pakistan and India, subsequently the secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan operates as a form of haunting in our families. My father remains silent about their paternal house in the Noakhali district of now Bangladesh. The stories from the partition, and mass migration across the borders remain as ghosts in our family closets. In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s my aunts (mother’s sisters) were married to professional men migrating to the United States. This newer chain of international migration to the US through routes of marriage and merit informs the present generation within our families. My interest in immigrant rights work stems from histories of migration, uprooting, and re-rooting within my family.

Secondly, my own life-trajectory and immigrant rights activism in the United States is largely informed through the experiences of my friends, the immigration reform in 1996, the passage of HIV Ban on immigration to the US in the early 1990’s, and post 9/11 national security practices. I began by helping friends with their asylum applications, and got connected to the (now defunct) Asylum Research Project at the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, and the immigrant rights working group at the AudreLorde Project in New York City. Since then, I helped co-found the Queer Immigrant Rights Project, and was awarded a Ford Foundation funded New Voices Fellowship to work with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and HIV+ immigrants in New York City. My fellowship provided me with opportunities to conduct research related to the relationship between sexuality, AIDS, and immigration laws in the US. Further, my work around lifting the travel/immigration ban on HIV positive people in the US brought me in contact with international organizations, national HIV and AIDS policy organizations such as the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Action AIDS, and the International Organization on Migration (IOM). I began to make connections between my personal life experiences with larger socio-economic trends.

TARSHI: Queering Immigration may sound a little novel to many of our readers. How would you explain this?

DD: Perhaps a different way to think about queering immigration is to ask, “How are bodies regulated through immigration laws?” Immigration policies related to reunion of family rely upon normative ideas of the family. The nuclear family model (husband and wife, and now increasingly gay and lesbian domestic partners) are privileged through laws which allow US citizens, or permanent residents with high income to support their partners for immigration benefits. This leaves single people, unmarried people, or those surviving domestic violence with severe predicaments. Further, immigration laws seek to regulate gender presentation. In the United States immigration officials have historically barred men and women with diverse gender and sexual presentations (Canaday, 2009). Margot Canaday writes about immigration officials taking pictures of bodily parts in order to decide if the migrant was perverse and pathologically unfit to be allowed entrance to the US. Similarly, there were moral character examinations: a ban on homosexuals in the US till 1990 and a ban on those living with HIV and AIDS to enter the US or apply for immigration till 2010. Queering examination requires interrogating these norms related to ‘normal’ bodies and the ways such norms shape immigration law as well as the lives of immigrants. In the context of the India and Bangladesh border, several Hijras work within the human smuggling trade since police are reluctant to body search them. Non-governmental organizations involved in working with Hijra, Kothis, and Kinnars report higher levels of violence upon Hijra, Kothi people who cross the borders in search of better livelihoods. Queering immigration requires an examination of policies, laws, and norms which work to construct certain bodies as undesirable for inclusion inside the nation state. Queering immigration requires a call to social action, which helps nurture a livable life for all kinds of unwanted bodies.

TARSHI: How does a person’s gender, sexual orientation or sexuality matter when they try to immigrate? Is a person required to reveal this identity, and how does that affect their chances of immigration?

DD: I think questions related to marital status, health status, income, and education disproportionately impact people from working income backgrounds, or those living with chronic illness and other forms of debilities. The militarisation of borders throughout the world, check-posts within places such as the Kashmir valley, the Pakistan and India borders impact women, Hijra and transgender people differently. The way you walk, present yourself at borders and airports draws attention to your gender presentation, and potentially sexuality. One doesn’t have to overtly reveal sexual or gender identity, some of the codes of conduct are informal. However, in overt cases such as tracking and recording health related information, finger printing, conducting moral turpitude related interviews, those living with chronic illness, previous records of drug use, histories of sex-work, and/or transgender identities are treated differently and often end up being excluded from the gates of different nation states.

TARSHI: What are some of the legal concerns for the government of the country they are trying to immigrate to? What barriers do they impose because of these concerns?

DD: Let me be a bit specific and share an example. People living with HIV and AIDS face several restrictions in mobility across international borders. There is a fear that they will spread the virus, and drive up the public health costs within destination countries. I have argued the HIV-related travel restrictions as a queer issue in my academic/activist work (DasGupta, 2012). In 2010, HIV travel and immigration restrictions were lifted in China, USA, India, and South Korea. (The Global Database Project). Although the restrictions have been lifted, South Korea still requires HIV testing of foreign nationals working in the country. In the US, while the federal ban has been removed, several states have laws against people living with HIV and AIDS. If you fail to inform your sexual partner about your HIV status, you can be arrested as a felon. Felony charges impact your ability to naturalize your status as a citizen, since this is considered moral turpitude. Stigma against those living with HIV is interconnected with criminalizing behaviors and bodies of those living with HIV and AIDS. Mobility restrictions operate not only as travel/immigration bans but also regulate the intimate lives of those living with HIV and AIDS. Criminalizing those living with HIV further marginalizes people from accessing treatment and halting the spread of the virus as soon as someone is detected living with HIV.

TARSHI: Do you work specifically with people from the Global South migrating into the US or do you work with people from other countries, and on reverse migration as well? Are the challenges different? If so, how?

DD: I work with people migrating from the Global South as well as Eastern European nations. In my recent research I am documenting activism mounted by Russian LGBT asylum-seekers, transgender asylum-seekers from countries such as Guyana, as well as farm-workers from Ecuador, and Mexico. I have recently started documenting life-stories of those who are returning to India and Brazil. Return migration creates a different set of challenges. How do those returning to India create their communities? There is a tremendous sense of loss while deciding to leave the US. Issues related to transfer of assets, reorienting to a different socio-political landscape, negotiating new laws and bank procedures are all a part of the everyday lives of those engaged in return migration.

I am interested in chain migration. There is cross-border movement from Bangladesh into India by workers in the service industry. Queer and women migrants often work in the service sector within the migrant labour market. I work with people who are part of a chain migration network. Young men and children running away from family violence and poverty in small towns from Bangladesh, and smaller towns around large Indian cities attempt to migrate to larger global cities such as Doha, Bangkok, London or New York. In my next project I am beginning to work with young runaway boys who cross the Indo-Bangladesh border in search of a livelihood.

TARSHI: What unique challenges does the LGBTQ immigrant community face as immigrants? Are they more vulnerable than the native LGBTQ population in the country, and why is it important to talk about their rights?

DD: Several unique challenges come to my mind. First of all, immigrant LGBTQ communities especially those marked as non-white have to deal with racism within their destination countries. Immigration laws privilege higher income coupled status immigrants over single and poor immigrants. LGBTQ migrants who are not skilled professionals or married are the most vulnerable for becoming undocumented. Vulnerability takes many forms, from being detained and deported to being denied access to housing, health care etc. Activism geared towards the rights of LGBTQ immigrants needs to be a priority within the global migrant rights movement, since many LGBTQ immigrants lack family as a safety net and live in a precarious state. I think there are different kinds of vulnerabilities for racialised LGBTQ people within the US (where I live). There is an epidemic of violence and police brutality upon transgender people of colour in the US. Poor homeless LGBTQ people and those living with AIDS are increasingly struggling with housing as Medicaid and AIDS housing is being reduced.

Governments across the world are cutting back on public budgets. This impacts the most marginalised people. Often, poor LGBTQ people, disabled people, and immigrants are the ones who are most vulnerable to these budget cuts. Immigrant rights activism needs to articulate these vulnerabilities through the language of human rights. Further, activism needs to centre transformative strategies, beyond legal rights to address the vulnerabilities of LGBTQ immigrants.

TARSHI: Is it common for persons who identify as LGBTQ to seek immigration or even asylum, because of restrictive laws, cultural stigma in their own countries? And if so, what are some of their expectations from the country they immigrate to? How often are these expectations met with?

DD: Applying for political asylum is a very tedious process. Some of the most vulnerable LGBT immigrants apply for political asylum based on sexual orientation. The process is very bureaucratic, with the entire pressure of proving past persecution on the immigrant. In the US one has to apply within one year of entering the country, which is hard for queer immigrants, since many of them live isolated the first few years and don’t know of the asylum provision. The US Department of Homeland Security does not release statistics related to success rate for all asylum applications. However, from my experience I can say asylum applications are difficult. The asylum seeker needs to frame their narrative as a victim seeking protection from the US Government. Asylum officers interrogate every aspect of the persecution. If you are suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, the entire process can be very emotionally triggering. If you are granted asylum you are unable to return to your country of origin, all of which create psychological trauma, a sense of disassociation from your country, communities of origin within the asylum seeker.

TARSHI: How does same sex marriage relate to immigration? What are the challenges for same sex spouses seeking immigration visas?

DD: In the US, the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) has for the longest time barred same sex married couples from accessing federal benefits including sponsoring their immigrant spouses for immigration purposes.

The Supreme Court upheld that Section 3 of DOMA is unconstitutional in July 2013. Since then the USCIS (US Citizenship and Immigration Services) has required that married gay and lesbian couples be recognized for immigration purposes. Couples marrying in states which recognize gay marriage including Washington DC are applying to sponsor their immigrant spouses.

TARSHI: How hard is it for a transperson to change their gender identity when on an immigrant visa? What challenges would they face?

DD: Quite difficult.One needs to have access to health insurance for the gender reassignment surgery and hormone therapy. If you are on an immigrant visa and do not have access to private health insurance, your access to surgery is extremely limited.

Finally, while applying for permanent residency (undergoing change of status from temporary visas to permanent resident status) one needs to submit proof of change in gender identity. Medical surgery is the only acceptable proof. Change of identity is therefore regulated through official paperwork.

TARSHI: Any final words of wisdom, insights or learning you would like to share either about what has been achieved or the challenges or both?

DD: I think the intersections between immigration, sexuality, gender, economic class, and disability status ought to be thoroughly taken up in multiple contexts. In the case of India I have worked with child rights organization such as Praajak Foundation which works with young runaway children from Bangladesh. Many of the young children live in railway stations. My next project is to work with creative artists who are utilizing art therapy with young runaway children living in railway stations, and in conflict areas across regional borders. The friendship networks of migrant young people (like that of the young men who work with Praajak Foundation) fascinate me. I believe along with policy changes, the next generation of migrant rights activism ought to centre intimacy, liveability, and friendship networks within which immigrants live and thrive.

References:

Canaday, Margot. 2009. The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth –Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The Global Database: http://hivtravel.org/Default.aspx?pageId=150

Resources: