Deena Mohamed, Egyptian artist, illustrator and designer, speaks to us about her art and her perspective on politics, patriarchy, feminism, and gender and sexuality. In 2013, Deena introduced Qahera, the Hijab wearing female superhero, to Egypt and to the world, challenging many existing perceptions of women in the Islamic world. Her first graphic novel, the award winning Shubeik Lubeik, has been published in Egypt in Arabic and the English translation is scheduled for publication in 2021.

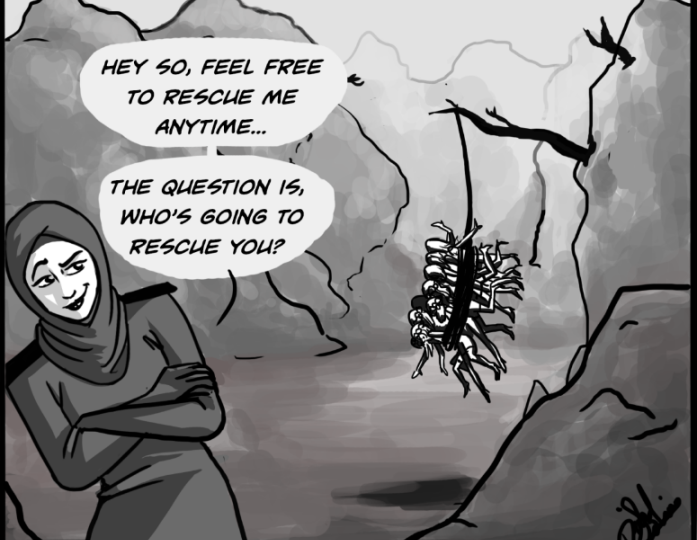

Shikha Aleya: Deena, we absolutely must begin with your feisty Qahera, superhero, whom you created five years ago! She is such an amazing character, unafraid of the violence around her, questioning not just patriarchal perspectives, but some feminist standpoints too. We know she inspires her fans – does she also inspire you? Please tell us about your relationship with this character.

Deena Mohamed: My relationship with Qahera is actually really complicated. I started the webcomic at the beginning of a rapid learning curve – or maybe creating it taught me a lot. But because of that, every comic always felt like old work, and with each comic I felt like I had learned something new and wanted to do better. For that reason, it was difficult for me to be proud of Qahera as an artist. I was always very critical of the comics, and a bit awed and bewildered by how much people loved it.

Now I’m five years older and I have enough distance to appreciate what I was trying to do. I’m glad Qahera exists and even though the comics aren’t perfect in a lot of ways, I’m grateful it touched so many. On a personal level, Qahera has helped me launch a career as an artist and I still get work, trips and interviews (like this one!) because of her, so I actually really appreciate her existence. I often said she’s just a fictional character with no ability to create real change, but to be fair she has helped me, her creator, a lot.

Shikha: Qahera has been an inspiration to many. In one of the earlier comics, Qahera has a fantasy of violence against a singer of songs with misogynistic lyrics. You depict both sides, with Qahera’s friend/peer questioning this response. Tell us what you think and feel about the effect of popular culture, song, film, dialogues and lyrics, on the way gender and sexuality play out in our lives.

Deena: I think everything contributes to how we view ourselves as a society, and I think it is actually difficult to discern how much of an effect a song or a movie can have on real life. Not just gender and sexuality, but also the patriarchy, authoritarianism, and traditions in the background that inform our gender and sexuality – these are things that are implicitly or explicitly upheld or challenged in everything we create and consume. But it’s also exhausting sometimes to think about every lyric from a critical standpoint. I think it’s healthy to examine where we stand every once in a while, and I think it’s good for creators to put out content that aims to improve people’s lives, but I also think we need to be practical about it.

There’s a relationship between media and reality – sometimes media is shaped by our reality, and sometimes media shapes it. It’s little wonder our music is misogynistic if it is informed by the misogyny of the singer, the songwriters, and the audience. We can’t act as if a song exists in a vacuum, but we also can’t pretend it’s harmless to celebrate their bad behaviour. I don’t have any smart conclusions to make about this. I just think all we can do is analyse our media and do our best to put forth better work.

Shikha: Please share your perspective on FEMEN, the radical activists, known internationally for their topless protests, as you have presented through early Qahera comics. Also, on the subjects of women, dress, patriarchy and politics – how have your thoughts progressed since you created Qahera? What are the sorts of reactions you’ve encountered, and conversations you have had on these issues?

Deena: I think the FEMEN comic was a turning point for me because it was the subject of a lot of criticism and academic exploration. This is where I learned a lot – I actually immediately agreed with a very solid criticism of the comic by a blogger named kawrage (it has unfortunately since been deleted with her account) but it highlighted the weaknesses of portraying FEMEN in such a superficial light, and making it about a physical threat or violence even metaphorically, because the problem with FEMEN is that they represent a colonialist and exclusionary version of feminism and even so they already face a lot of violence, and the comic doesn’t address this well enough. This critique really opened my mind and has made me a lot more conscious and thorough about the comics I drew afterwards.

I don’t think my thoughts have actually changed much since then. I feel like one of my main problems is that we continue to have the same conversations over and over. Yes, Muslim women can be feminists. Yes, veiled women can be superheroes. Yes, some veiled women are forced to wear it. Yes, forcing them to take it off is bad too. Yes, the problem is patriarchy/classism/capitalism worldwide. Yes, I don’t think all white feminists are bad, yes neither modesty nor nudity are morally superior choices. Honestly, it’s become evident how little people listen.

Shikha: Now a quick question about some of your other, and more recent artwork. In InkTober 2018, the October art challenge, you have sketched ‘Guarded’, with a woman and a man next to each other traveling somewhere, ‘Clock’ where a young girl and a woman overshadowing her are in parallel form and ‘Weak’, with a young boy facing large weights. What are your thoughts and feelings behind these?

Deena: Honestly, I was kind of constricted with the InkTober prompts, so I was trying to find ways that fit the InkTober theme and also my own personal theme (of wishes). My goal with InkTober this year was to try and portray as many desires as possible. Sometimes the prompt was inspiring, as in the case of ‘guarded’ and ‘clock,’ which I think turned out pretty well. When I hear the word guarded, my mind automatically goes to how women conduct themselves in public. There are so many invisible defenses we put up around ourselves daily. Clock is about youth, and I don’t think it particularly relates to a gender so much as to the universal fear of aging. As for weak, it’s a relatively straightforward one. It might seem metaphorical, but honestly I was thinking about weightlifting. I want to be strong enough to lift giant weights too!

Shikha: Do you find your experiences and engagements through social media satisfying in terms of the communication and impact you have observed? What are the upsides and downsides of the activism through art and popular culture that you experience?

Deena: I don’t consider myself an activist. One of the problems of social media I think is overstating the impact of people with big followings and understating the impact of people who work tirelessly offline. I think social media is an extremely useful and adaptive tool for social outreach, but at the height of their success I never considered these comics activism. I am always reluctant to overstate my impact too. I think representation is important, but I have always been wary of giving these comics too much credit for things like impact and activism at a time when we were going through so much upheaval. Qahera is cool because she reflected the reality of real women, not the other way around.

I think it is a deeply satisfying form of communication though. Without social media, as an Egyptian artist (and a student at the time) I would have never, ever been able to reach the audience I did. I made so many valuable connections and learned so much and it was all possible thanks to the Internet. For many of us in the third world, it’s our sole source of education, promotion and work all in one. It’s where I taught myself to draw and where I would later post my art, so I am not understating its importance to me.

It is a double-edged weapon though, especially when it comes to engagement. When you rely on virality, audience and outreach to promote your career, you can easily fall victim to sensationalism and clickbait. I was happy I never needed to monetise Qahera, because it meant I never worried about appealing to a mass audience. I think these comics could have easily become controversial attention-seeking endeavours to attract as many views as possible, and I was always worried when I posted them about my intentions. I tried to maintain my integrity in the topics I chose in that they were things I genuinely believed in and wanted to talk about, and not things I thought would gather the most interest.

As an artist online, it’s easy to equate interest with success and likes with quality. But that’s not always true. The things that gather the most attention often do not have room for nuance or truth, especially pop culture activism that is so reductive on so many topics about identity and politics. I think the virality of these comics and my critical approach to them taught me a valuable lesson: it doesn’t matter how many other people like my work if I’m not proud of it myself. And that really pushed me to work harder and learn more. It’s probably also why the comics stopped coming, because it became difficult to do justice to a topic when I suddenly lost that teenage confidence and self-righteousness, and became a little anxious about the real impact of my work.

Shikha: Thank you very much for this interview Deena! Now a last question. Please tell us a little bit about yourself, past and present. Were you to sketch yourself into a comic art character, what would be the most important aspects of this character?

Deena: I think I’ve talked a lot about myself in this interview already! I guess right now I’m excited about where I am as an artist – I feel like I’ve grown from my previous experiences and I’m proud of the work I’m doing now. Qahera gave me a headstart in the comics industry, and I’m happy that I get to do a lot of comics for kids and NGOs on important topics that hopefully improve someone’s day. I’m also currently working on a graphic novel trilogy which is an urban fantasy about wishes. It was nice to be able to relax into a graphic novel format after being restricted to short webcomics, because I love telling long, complicated stories, and I’ve been so happy with people’s reactions so far.

The first part of it has just been released in Arabic and the English translation of all three parts will be published by Pantheon (US) and Granta (UK) in 2021. These are both really big publishers (Pantheon has published some of the biggest graphic novels to date, like Maus and Persepolis) and without Qahera, I never would have had the opportunity to see my work on the international stage. So these are things I’m really, genuinely excited about, and honoured by.

I suspect I am already a comic character, because I wear like one outfit all the time and I am usually pretty sleepy as a personality trait. I think I would be a really good background character, like Naruto’s comic relief friend who is always either working or sleeping, and rants about Naruto every now and then.

Cover Image: Qahera comics