For the two-part interview section of this month’s In Plainspeak, Shikha Aleya spoke to a few individuals who continue to push the boundaries of their work, art, and social norms, and expand the understanding of diversity and sexuality. We requested each of our interviewees to contribute from their own understanding and help build a broad perspective on the subject of diversity and sexuality.

A warm thank you to all, for making the time and space for this interview.

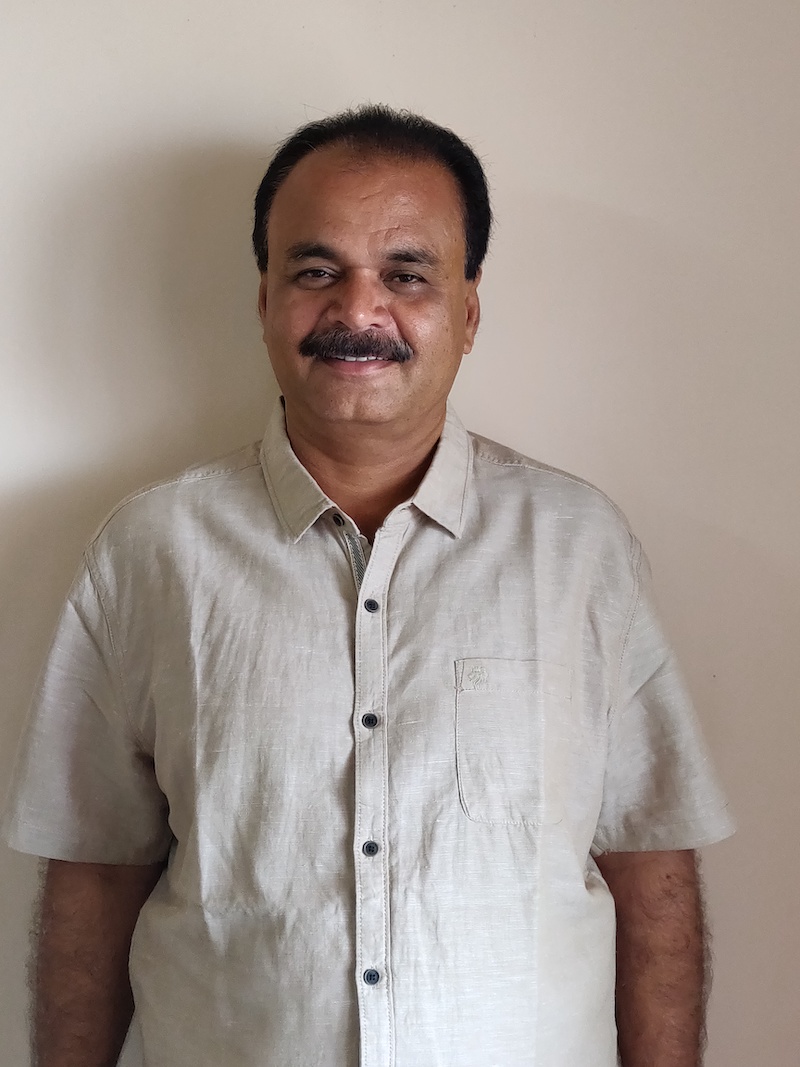

Dr. P Balasubramanian (Balu) is a Social Scientist, trained in Demography. He is the Executive Director of RUWSEC – Rural Women’s Social Education Centre – a dalit women’s organisation in Tamil Nadu. He has worked extensively as a researcher and activist on gender, and sexual and reproductive rights over 25 years. Balu has focused attention upon sexual and reproductive health and rights, on issues related to women’s rights, autonomy and bodily integrity, and has worked on programs for adolescents and young people. In collaboration with The Asian-Pacific Resource & Research Centre for Women (ARROW) he prepared research reports on sexual and reproductive health and rights in India, religious fundamentalism and impacts on young people’s sexuality. Balu has published more than 20 research articles/reports in both national and international peer reviewed journals.

Meena Seshu works with SANGRAM which is a health and human rights NGO based in the rural districts of western Maharashtra and north Karnataka that works to address social inequality and to promote justice amongst marginalised communities, discriminated against because of sexual preference, sex work, HIV status, gender, caste and religious minority. It focuses on building solidarity amongst diverse and marginalised communities by using a rights-centred approach to self-determination that organises the voiceless to collectivise as a key strategy. Accordingly SANGRAM’s collectives include Veshya Anyay Mukti Parishad, VAMP (Sex workers fight injustice), Vidrohi Mahila Manch, VMM (Rural women), Nazariya (Muslim women), Muskan (Collective of Male and Trans* sex workers), Mitra (Children of sex workers) and VAMP Plus (PLHIV group).

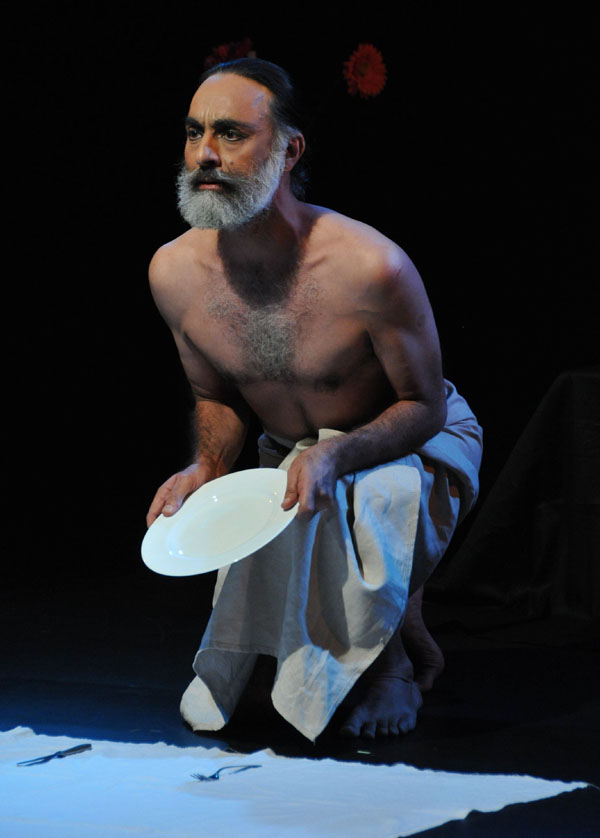

Navtej Singh Johar, is an award winning Bharatnatyam dancer and choreographer. Through his work and art, he explores and presents themes focusing on the body, on sexuality and boundaries. In 2016, he was one of six individuals who together filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court of India challenging IPC Section 377, in continuation of a long history of efforts and activism by many people and organisations. This law was read down in the 2018 judgement on Navtej Singh Johar and others v. Union of India, where the Supreme Court held that “Section 377 of the Penal Code, in so far as it criminalises consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex, is unconstitutional”.

Shamini Kothari currently works as Writer/Editor at Nirantar: A Centre for Gender and Education, Delhi. She holds a Masters Degree in Sexual Dissidence from the University of Sussex and also previously co-founded QueerAbad, Ahmedabad’s queer-ally support space. She occasionally writes about issues related to gender and sexuality from a cultural perspective.

Dr. Subha Sri Balakrishnan, is a member of CommonHealth India, and a gynaecologist working with RUWSEC, Rural Women’s Social Education Centre, a dalit women’s organisation in Tamil Nadu. She has been working on issues of gender equality, health and the sexual and reproductive rights of women.

Sujata Goenka is a disability rights activist, a trained and experienced special educator and counsellor, and a pranic healer exploring energy healing processes. She has lived experience of the complex issues of mobility, accessibility, support and social acceptance, having grown up with cerebral palsy. In 2013 she received the Kiran Award for lifetime work in disability. She worked at the Naz Foundation on care issues of persons living with HIV and AIDS. She is currently part of the editorial team at Pinkishe, an NGO concentrating its efforts on the empowerment of women and girls.

In Part 1 of this interview, each interviewee addresses aspects of sexuality and diversity from their own particular space of personal knowledge, as well as work, advocacy and activism.

Shikha Aleya: Based on your experiences, what are your top-of-the-mind thoughts, and immediate feelings, on the subject of Diversity and Sexuality? Please tell us a little bit about why you think and feel as you do.

Navtej Singh Johar: This is not a simple question, and I hope my answer does not get too convoluted. Diversity and sexuality are both givens and stem from the body! Each one of us is differently endowed on the bodily level, no matter how we may choose to exercise or own this difference. However, each society dictates terms and wishes to exercise control over this diversity. One way it does so is by floating “ideas” that attempt to standardise this diversity, by proposing artificial binaries. Night/day, inside/outside are real binaries, however, moral/immoral, good/bad, Hindu/Muslim, gay/straight are constructs, but they become so normalised that they can be confused for binaries. I have the choice to resist, or buy into and participate in these constructed binaries. And the moment I buy into them, I implicate myself in the loss of my own power to remain freely diverse. Thus, by doing so, a very core part of me gets compromised and subsequently seeks to compromise others.

So, the first thing we need to be super wary about is not to buy into populist ideas. There are ideas galore, first and foremost there is this virtually inescapable umbrella “idea” of India – spiritual, eternally wise, non-violent, tolerant. Post-Enlightenment, the idea of “mind over matter”, which translates into “mind over body” or “man over Nature” has been entrenched in our Modern psyches, and this in turn leads to the revised “ideas” of the body: the moral body, the Indian body, the Sikh body, the gendered body, the sexual body, the rational body, the domesticated body, the pure body, the polluted body, the ideal body, the cosmetic body and so on. And we are perforce dealt the option of choosing to either subscribe to or reject these ideas. This is where I actually see a catch, as even resisting an idea makes us engage with it and thereby obliquely support and sustain it, even if we intend to reject it. The “idea” comes with an inbuilt dynamic that warrants polarisation, and therein lies the power, tyranny and sustainability of the idea. The “idea” thrives on polarisation, and the drama of polarisation continuously serves to deflect attention from what “is”, i.e. lived experience, lived history, human relations, insight, all of which emerge out of the body. The “idea” to my mind, thus, stands in direct opposition to the body. It has thus to be nullified, but without getting into a polarised, pitched fight.

Being a long-term practitioner of yoga, dance and somatics, my focus or touchstone has been the body. I see with ever more clarity the distinction between the body that “is”– this incredibly beautiful thing that is innately intelligent, intrinsically truthful, and sensitively insightful – and the “ideas” about the body. Ideas that are categorically mean, hostile and dismissive of the body, their main aim being the domestication and standardisation of the body. Based upon these populist ideas, each culture sanctions its own set of entitlements. And if you feel entitled, it means that you have somewhere bought into an “idea” or an ideology that your environment supports but one that may be actually unequal, however it happens to suit and favour your sense of belonging and security. So, my fight is first and foremost against the construct of the “idea” and the entitlements that ensue out of it. But then, I am equally wary of becoming self-righteous, strident, or belligerent about my contrarian position because that too would arrest me in one polar opposite and not allow me to centrally occupy my body that “is”. So, I find a catch-22 in resisting the domestication of the body on the one hand, and fighting a politically correct and charged battle against the powers-that-might-be, on the other.

Shamini Kothari: Although, I see the importance of diversity as an idea I often find it a watered-down version to think through the politics of difference. Diversity to me ends up being a liberal articulation (“the unity in diversity”) of structural differences that mark different bodies and lives. What I mean to say is that when we think of many feminisms or multiple sexual identities/expressions, we are not speaking about them in isolation. Most of the differences are born of a context that is further marked by class/caste/ethnicity/language and so on. These differences or tensions are crucial to think through the politics of gender and sexuality. I may exist in a room full of diverse sexualities but we may all belong to a higher caste and that is when an isolated notion of diversity becomes violent and exclusive. So perhaps, my immediate feeling towards ‘diversity and sexuality’ is one of skepticism. While I say this, I realise the importance of mobilising around difference and the politics I hope to practice and live by is one where we shift from diversity to difference.

Sujata Goenka: Women still feel shy about expressing their sexuality; a disabled woman has to be very bold to do so. The need to educate society about their sexual needs is largely ignored, as it is thought of as shameful. As a counsellor, I have found that parents of children with disabilities are reluctant to accept the sexuality of their child. They cannot understand how a young adult with an intellectual disability and the IQ of a toddler can have sexual urges. A demand for marriage is often looked at with great disgust. Even individuals with spinal cord injuries who wish to please their partners are looked at with amazement. Very often people with chronic illnesses go into deep depression when they feel the loss of their sexuality.

Professionals in the rehabilitation field working in schools and institutions for persons with disabilities must shed their inhibitions and start viewing sexuality as a part of rehabilitation programs. There are many people involved with adult rehabilitation programs. They focus on just economic rehabilitation and the training focus is on daily living skills. Sexual rehabilitation is lost in this approach. A paradigm shift is essential from just the roti kapda makan (food, clothing, shelter) thinking to understanding the diverse aspirations of people for the finer things in life. Sexuality is the most natural of all aspects of life and it must be addressed and not suppressed.

Subha Sri: At RUWSEC, we work with different community groups and also run a clinic providing reproductive health care and other primary health care services. As part of this, the diverse groups we work with include dalits, religious minorities, and people of different ages and different genders.

What I have learned over the years of working with RUWSEC is that sexuality is a key feature of the personal lives of everyone, whatever group they come from or identify with. The expressions of this sexuality vary widely though and are very deeply influenced by the traditions and culture of those groups and determine the normative behaviour of that group. One needs to be always aware of this, especially when working on issues of sexual and reproductive health. So, the way a dalit woman expresses her sexuality would be very different from the notions and expressions of sexuality of an upper caste adolescent boy. Nevertheless, this expression of sexuality is a key determinant of their sexual and reproductive health in each case.

One gap that I feel we in RUWSEC need to address is that, being a community-based organisation, we have not engaged adequately in our own community with diversity, on issues such as disability and sexual and gender diversity. This needs strengthening.

Meena Seshu: Diverse communities of people experience varying types, and differing degrees of social injustice, because of endemic social intolerance of difference and unbending social and religious morality that often judges them based on normative notions of ‘acceptable sexuality’. Each group has its own problems arising from how they are regarded as ‘other’, and find their own ways and means of coping. These communities include sex workers, men who have sex with men, people living with HIV, religious minorities, LGBT*QI+ people, and women and orphans who are being pushed to the margins by a society that has condemned their very existence. This marginalisation has led to a total denial of the right to lead a life free of discrimination, inequality and violence.

Balu (P. Balasubramanian): Generally in our society sexuality is viewed in a negative way and is a very sensitive subject. It appears that it should not be discussed even among married couples. There are so many socio-cultural and gender related factors that influence the approach to sexuality. There are also many taboos and misbeliefs surrounding it. In such a situation, adolescent and young people’s sexuality is a neglected subject. There is strong opposition from fundamentalists, and politicians with conservative ideas continue their agitation to ban sexuality education. There are many instances of unprotected sex, unintended pregnancies, early marriages, sexual violence and coercive sex. The early age of marriage of women with poor sexual and reproductive health knowledge has wider social and health consequences for the young population. Young couples married at an early age are forced to have children soon after marriage, and also opt for female surgical sterilisation operation at a very young age. So, educating adolescents and young people on positive sexuality is very important. It should be given top priority. Our approach should be sex positive and not negative.

Further, issues related to LGBT*QI+ people are enormous and not recognised. Diversity in gender and sexuality should be addressed through creating strong awareness at a larger level; that sex, though associated in the common perception with biology, is strongly socially determined. Sex is not always binary and likewise sexuality is also not confined to certain normative ideas.

Look out for Part 2 of this interview in our mid-month issue.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।