Kiran Bhat is an author and polyglot who speaks 12 languages, and has written in English, Kannada, Spanish, Turkish, Portuguese, and Mandarin. Kiran has recently published Speaking in Tongues, a book of poems written in Spanish, Mandarin and Turkish. Kiran has travelled in over 130 countries, lived in 18, and calls himself a global nomad. Author of the on-going digital novel, Girar, being written in instalments spanning 2021 to 2029, Kiran says, “More and more people need to learn that they really can identify with a larger range of humans than they realize, and that becoming connected and close to such people will help them embrace those who are different.”

Shikha Aleya (SA): Kiran, hi, we’re very happy to have you back in this issue of In Plainspeak to talk about narratives and sexuality. In an earlier interview, exactly three years ago, we spoke of literature and sexuality. To jump right in, these two territories, narrative – and literature! How are they distinct, how do they connect? And how is understanding this, important?

Kiran Bhat (KB): Narrative, as I understand it, is a story that we disperse in the hopes that it will impact or resonate with someone else. Literature is the canonisation of a narrative that has remained of importance to a community or culture, and gets passed on in the hope that it keeps inspiring others decades or centuries after the storyteller has passed. While a lot of literature is of value to anyone who comes across it, there is still a lot of politics as to which narratives become included as literature, both in the contemporary and ancient context. A lot of great and powerful writing from less thought of cultures gets ignored. We tend to read more works canonised out of the West than brilliant pieces of literature in Vietnamese or Tamil. I think that we must work harder to make sure that narratives of importance that are not yet being recognised as literature are brought to the forefront, so that they can continue to inspire people who deserve to hear these tales. That is something the younger generation needs to think about, and it’s something we have to build up a lot more in India, particularly as we build up our academic and cultural spaces here.

SA: As a writer, you have added sexuality to these themes. What are some of the most interesting finds that this space of interconnected themes has revealed to you?

KB: If I weren’t a queer artist I don’t know if I would be as borderless as I am. I don’t really see the need for division between male and female, heterosexual and homosexual. Conversely I don’t see the reason why we have to delineate people based on nationality or race either. Why does one person cross a border and become Pakistani, and one remain on another side of a border as Indian? It seems ludicrous to me.

So I am realising now that for me the space of borderlessness applies to everything. It applies to the physical and topographical border as it does to the borders we create between gender and their expressions. I think I would like to argue for a truly borderless understanding of the world. That means no demarcation between genders, no demarcations between nationalities, no demarcation of any sort between any sort of human expression.

Let humanity and any form it demands to take flow.

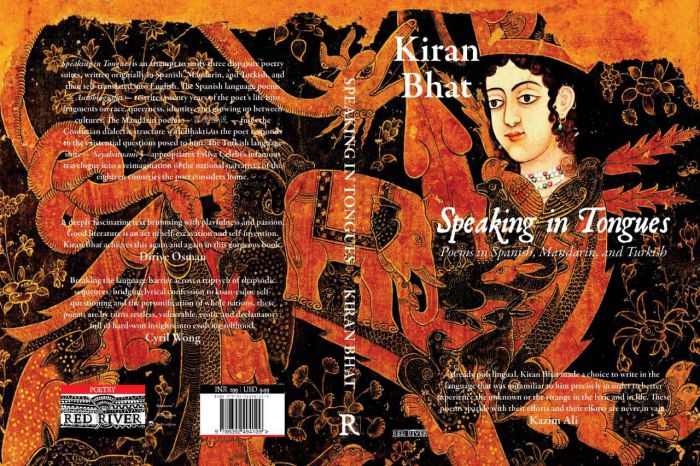

SA: A borderless understanding of the world would mean a complete shift in the way we approach many themes. Kiran, tell us a bit about your new book of poems, Speaking in Tongues. Would you say poetry engages differently with socio-cultural narratives, across languages, and with sexuality?

KB: Speaking in Tongues is a collection of three suites of poems written in Spanish, Mandarin and Turkish and represented in English. The Spanish poems are my biography, the Mandarin poems are my thoughts on love and life and the human way of thinking, and the Turkish poems are a summation of my homes and what they mean to me. I think each suite personifies my perception of the world in a different way, and has a lot to teach. At the core, in presenting poems in three different foreign tongues one side and then my native tongue English on the other, I am using the act of writing outside of my comfort zone to connect with something very much outside of me, and to bridge the gap between myself and that foreign space.

Poetry is very different from writing fiction. It’s more to the point, it’s more personal, and it’s more broken. I think writing in poetry across languages was a means to build a deeper relationship to myself and that foreign tongue. My poems actively engage with my sexuality because I am gay, but I don’t see the project as related to my sexuality other than that happens to be a part of who I am.

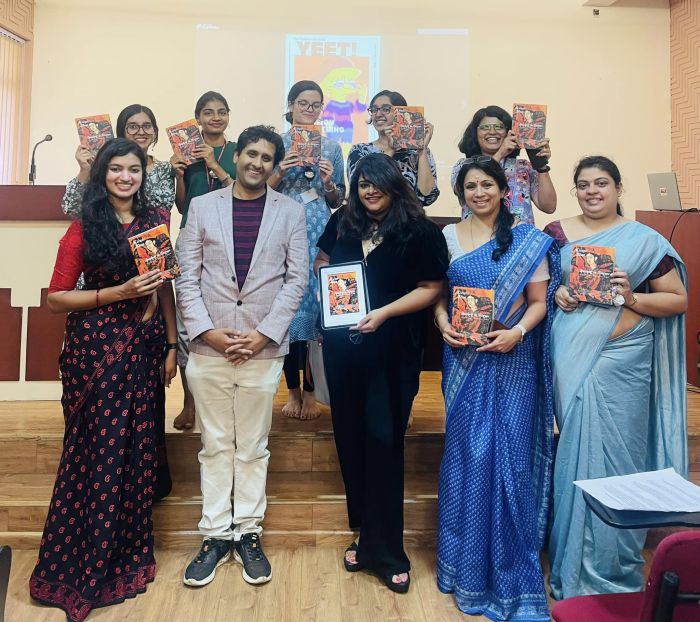

SA: This year you have spent a lot of time with young people, speaking at engagements in educational institutions. What are some of the things young people have said to you, or asked you at these engagements? As a take home thought, what would be your key messages to young people today, on the experience of sexuality and the narratives in our lives?

KB: I have spent the last few weeks in various parts of Kolkata, Kerala, and Goa visiting various colleges, giving discourses about global consciousness, and talking about my books. Honestly most of the questions that were brought up involved the youngsters’ engagement with the greater world. We talked about notions of cultural appropriation, how to travel more easily to foreign countries, and how to learn new languages. One student even showed me a poem she wrote in Turkish and asked me to give my thoughts on it! I don’t think my sexuality or sexuality as a whole was brought up

One thing that is interesting to note is that for this younger generation, particularly if they were raised in urban centres, sexual exploration is taken for granted. More and more people are experimenting with their gender presentation and who they openly date. As we live in a world where there is still a lot of tension between younger and older generation, urban and rural, cosmopolitan and nativist, I hope that more and more youngsters remain encouraged to experiment and imagine their selfhoods in different ways. I hope they never lose this bravery, no matter the tension it might create in the community. I hope our values continue to change and evolve and lead to a more inclusive world for people no matter where they come from.