Recently, the President of the European Commission Ursula Von Der Leyen, and the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, visited the President of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The meeting, that was in part to discuss women’s rights, caused a diplomatic kerfuffle

because only two chairs were provided for, and ironically, Von Der Leyen was the one left to sit on a couch on the side. Neither of the men batted an eyelash even though she immediately expressed her surprise. Neither of them thought to pause and ask an aide to bring another chair.

This incident is reflective of the general disregard of women’s leadership, and of women having to continue to fight for their right to have a seat at the table and an equal space at the workplace. Even when they manage to reach the top of their field, they are still excluded and slighted, such as in this incident in Turkey. Whether or not these incidents are intentional is yet to be determined because we do not have enough data or information about the various ways women are being left out or left behind. It is a never-ending cycle of a chicken-and-egg situation where women are not in the limelight, people in power (usually men) don’t think it is important to commission research on topics related to different aspects of women’s lives, and this leads to an invisibility and lack of understanding of women’s lived reality. But, the little data we do have points to the fact that we need more stories, reference points, and tangible information to challenge the status quo.

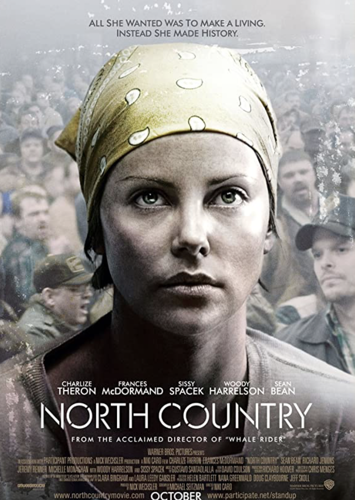

However, it is not easy to do so. I recently watched North Country on Netflix, a movie based on a true story of a woman’s fight for equality at the workplace. It is based on the case, Jenson vs Eveleth Mines, in the United States in which Lois Jenson, fought for the right to work as a miner, and the right to work free of sexual harassment. She won the landmark 1984 lawsuit, which was the first class-action lawsuit on sexual harassment at the workplace in the United States and resulted in companies/organisations having to introduce sexual harassment policies at the workplace.

In the movie, Charlize Theron plays Josey Aimes, a woman who flees from her abusive husband and returns to her mining hometown with her two children in 1989. Her parents are unhappy that she has left her husband, and are even more unhappy when she tells them that she does not plan to return to him. To her father’s horror, she decides to take up a job as a coal miner alongside him in the town’s mine as it pays well. In April 1974 a “consent decree” between nine of the country’s largest steel companies and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had been passed agreeing to hire women and minorities for 20 percent of new jobs. Aimes is part of the new batch of women who join the mine, allowing her to earn six times what she earned at her job washing hair. However, her father believes, like all the other men in the town and the company, that a woman’s place is at home and not at the workplace. They also believe that women are taking jobs away from men.

To express their dissatisfaction, the male coal miners use every opportunity to harass their women colleagues. They sexualise the workplace with constant offensive verbal and visual anti-women references portraying the women as sexual objects. They smear the walls of the women’s locker room with faeces, write sexist and derogatory comments on them, and even sexually harass the women. When the women verbally complain to their immediate supervisors and the manager of the mine, the harassment grows worse. Josey is almost sexually assaulted by another miner, Bobby Sharpe, who was the bully at her high school. The mine has no proper facilities for women and a portable toilet is installed based on their demands. However, the men constantly make fun of the women often ignoring their privacy when they have to take a bio-break and even lift, sway and drop the toilet on its side while a woman is inside, using it. Yet, the culture at the workplace demands that the women stay quiet whilst the men crack jokes and play these vicious pranks on them. All of these instances of harassment are dismissed as pure fun and the women positioned as lacking in humour. In fact, they are told that if they wanted to work as a man, they should play along, stay silent and bear it like a man.

However, Josey is having none of it and decides to complain. She does this after the harassment she faces at the workplace spills into her daily life and Bobby Sharpe’s wife insults her at her son’s hockey game in front of the entire crowd at the stadium. Sharpe’s wife accuses her of having an affair with her husband when, in fact, Josie has done nothing of the sort and just wants to stay away from Bobby. When she complains about the harassment she has faced, the management, instead of taking note, asks her to hand in her resignation.

So, she takes them to court and during the proceedings, is subject to blaming and shaming, having her past intensely scrutinised, being labelled sexually promiscuous and considered being of ill-character. It turns out that she had been raped by a teacher at her high school when she was 16 and though Bobby Sharpe had witnessed it, he did not help her himself, call for help, or report it. Instead, he spread rumours about her. Josie got pregnant as a result of the rape and didn’t have the courage to tell her parents about it. So, she lived with the stigma of being ‘promiscuous’. She also made poor choices in her relationships as a result of the trauma, deep-rooted sexism, misogyny and patriarchy she was constantly exposed to in her socio-cultural milieu. Thus she ends up with abusive partners, including her husband.

But, when she does gather the courage to make a break for it and start anew, she is met with resentment, harassment, and disapproval from her family, co-workers, and the town. During the case proceedings, the judge tells her that if she is able to convince three other women to join her in filing the lawsuit, he would be willing to hear it. Through her testimony, she is able to convince her family and friends to stand with her, and several other women decide to join her in her fight.

The sad reality is that although it takes one courageous person to speak up, they are often never believed because of the ‘lack of evidence’. It is their word against the man’s, who is seen to be important and powerful, and therefore right, while the woman is accused of “asking for it” and provoking the harassment. It is because of the lack of data that one cannot join the dots and see the patterns and trends of this harmful culture of misogyny and sexism and how it physically and mentally traumatises women, makes them vulnerable to further abuse and creates an environment that is hostile. In fact, bystanders around them become complicit in the abuse because they are unable to recognise these incidents as harassment and do not know how or when to intervene.

Josey’s case as well as other such cases, as seen in the #MeToo movement are far from being one-off or rare incidents. If there were no stigma around the issue that put the onus on the survivor to keep the “honour” of the family and/or community, would we have more people speaking up or reporting these incidents officially? In the absence of data or information, the burden is on the survivor to prove their innocence.

It is extremely important to collect these stories and document them formally as they have a direct correlation to how we view women, treat them, and provide them opportunities. In my own experience, anonymous reporting like we have at Safecity is extremely important in building a database of incidents that can further our own understanding of the various forms of sexual harassment, identify patterns and trends that promote and contribute to the violence, and create a repository of evidence to demand accountability. The discrimination and violence is so steeped in our socio-cultural understanding of gender that it often translates into harmful and limiting gender stereotypes that not only affect a woman’s right to work but also the enabling environment she deserves at the workplace. Whether it is Josey Aimes or Ursula von der Leyen, this discrimination can take many different forms, and without collecting data and us speaking, it is difficult to challenge and counter it.