Some propositions:

Nothing ‘activates’ like art. (I’ll speak here of theatre). It can touch, stir the senses, the head, the heart, the body, our spirit, our ‘social self’, if you like- all together. It takes just one deeply felt action, sourced from a significant human experience, striking through the air, with beauty, to rouse an audience into another way of looking at the world.

We are probably better off if we start with the assumption that activist theatre shoulddo much more than rally the audience on issue(s) and drive them to seek ‘change’.

In fact, some part of ‘activising’ is lost if artists think they have found the ‘solution’ and are offering it to the audience through a performance.To hand out a solution,or end by saying ‘So what are we going to do about it?, is a kind of manipulation of audience’s thoughts and feelings rather than ‘activising’ them.

It is not the audience alone that needs to be ‘activised’. The artists should themselves feel challenged by their creation, even as they perform, provoke, rouse, search. Performing the material shouldn’t come easy – words and actions should suggest and point to a range of human experience, to much more than what the words themselves suggest.After all the material is to do with social and political processes – so it is complex, it holds ‘secrets’, most of it is not visible, tangible, it is certainly not easy to lay bare. Also, we must allow people to make sense of it in their own ways, given their background.

And in terms of the art forms too it’s best when it’s many things at the same time – attractive, disturbing, puzzling, even funny. In the best tradition of activism, the performers ‘propose’, and lay the piece ‘out there’ for themselves and the audience to ‘enter’, to struggle and grapple with, to be moved and also challenged by.

Should activism and ‘call for change’ be clubbed together? What about activising theatre itself in a way that challenges the conventional artist – audience relationship, where one is meant to ‘activise’ and the other ‘receives’ it?

Augusto Boal initiated a theatre where the audience could

As art activists we sometimes approach our work with ‘gut feelings’ i.e. we sentimentalise when we initially set out to provoke. We often mistake one for the other.The problem with sentimentality is that it takes up all the room so that there’s none left for the audience to ‘enter’ the action and do its own thinking, feeling, deciding, acting (in life, not in the theatre sense). I think there’s a difference between being ‘moved’ and being ‘sentimented’. The former has the capacity to generate a ‘self -dialogue’ in the audience, even if only for a moment. The latter only serves to pull at a single chord in us (usually pity) and ‘freeze’ us into a ‘state’ -a manipulation, in a sense.

It’s not enough to simply ‘go with the gut’!

The cow comes to mind – she chews and chews….her gut sits down there in her belly, ‘feeding’ the cud in her mouth with juices made by her body. And finally, she knows exactly when she has arrived at the right ‘mix’ and then she swallows…..and swallows so it reaches, nourishes the far corners of her body. It certainly takes a lot of juice!

We need to be particularly alert when dealing with themes like gender / sexuality.

In uttering ‘walk’ (in the performance, ‘Walk’ made in response to the horrific gang rape of Jyoti Pande). I try to simultaneously sense the bodily action of the leg slowly going up, as if I am doing it for the first time in my life, to sense what it means to cover ground, both in terms of physical space and to ask myself if I am ready to open spaces in my mind, to find in that instant a connection with the audience – that I am doing an action that we take for granted because ALL of us do at some point in the day…everyday…, to celebrate the fact that my (our) simple capacity to put one leg after the other means I can reach all corners of the world, that Jyoti will never enjoy it again and so I must try and do it for her, that one step leads to the next and the next. In fact, for me, the thought, ‘I want the freedom to walk unhindered’, is only one part of it.

Yes, to see a woman cry out in despair in a street play can be moving. But it all depends on the continuum of actions / events that the cry is a part of- what action / moment comes before and after the cry, where it is leading to, what larger universe of social experience and processes it seeks to connect to? What kind of inner dialogue is the character going through, grappling with? These are only some questions the artist – creators need to ask during the making process.

As political artists we need to sharpen our understanding of social and political processes as much as we need to refine our means of artistic expression. Usually, in activist theatre, we often forsake the latter because we imagine art is only a ‘means’ to carry the message. What we don’t realise is that the content can become distorted if the artistic forms and devices have not been worked upon with aesthetic care and understanding. So, in creating ‘poor theatre’ (usually, in activist theatre there are no elaborate sets and costumes), we leave theatre poor.

One of the challenges in dealing with gender is that the body itself is the primary message -the sex of the performer’s body – fully present, through which a gamut of human experience, themes, lives, thoughts and emotions will be represented.

In activist theatre, the bodyseems to become larger than life -the sex of the performer ‘speaks’, even before s/he has uttered the first word. And therein lies the artistic challenge. Theatre’s primary instrument is the performer’s body -how do we look at and ‘play’ with the whole spectrum of fe / male bodies so that the audience (and the actors) are being continuously challenged by what they see, hear and experience in the performance. In fact, the way we have largely marginalised the transgender performer’s body so far proves the point.

More – as feminists we know that gender is a thread that runs through most aspects of life. Yet, most activist theatre, certainly to do with women’s issues,is reactive -it addresses problems of discrimination, harassment and atrocities. For instance, we don’t make enough performances that look at ‘daily life’ -where people are ‘simply going through life.’ What is in the family system that gradually narrows down the girl’s choices in regard to a range of issues? Where and how does it set in from childhood? What is the whole family /society losing out on by not bringing her up to be her own agency? What are the linkages between systems / spheres in children’s lives e.g. friends / school and the family? What about the impact of institutions beyond and their impact on children of all sexes? Where are the nooks and crevices, the small and big moments in daily life when people of all sexes can negotiate and take their life (and others’ lives) in a different direction?

More importantly, how do we create exciting drama, not just street theatre, where sometimes the participants can take hold of the reins of drama and steer it for themselves. How can we start drama with a statue in a museum with school children, in a hospital with the patients in the general ward, with dislocated people resettled in a new place?

Is there a case for broadening our understanding of theatre so that it’s not about ‘theatre’ versus ‘activist theatre’? Maybe it’s more about activising theatre itself. As artists we need to find new ways to make art that jogs all of us out of crusty ways of thinking and living and bring art closer to people’s lives, of taking it in many new forms to unusual spaces.

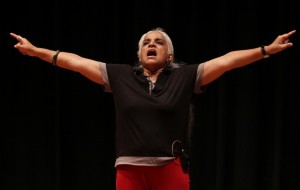

Pic Source: S. Thyagaraja