In many ways, addressing issues related to parenting and sexuality is mediated by how childhood is viewed and understood by parents, families, society and governments. At the heart of this gaze are issues of consent and to what extent we have a nuanced understanding vis-à-vis children and young people and their sexuality. Being able to talk about children and sexuality is a deeply discomforting issue for many adults. Today, talking about it or seen to abetting it in some way can attract punishment and incarceration.

Shohini Ghosh uses examples from art history and photography as an interesting analytical tool to examine both the historical context as well as contemporary shifts in the way childhood is viewed.

Children, Representation and Consent

There are two words most commonly associated with childhood: happy and innocent. Childhood is supposed to be happy, and it is supposed to be innocent.

Especially in the Global South, we are confronted with moments that expose the structural underpinnings of such a conceptualisation; class privilege, for instance, is a general prerequisite for a ‘happy’ and ‘innocent’ childhood. Despite this, and despite knowing that childhood can be buffeted by loss and grief, we still cling to an idealisation of childhood.

Where did this idealisation come from?

A number of scholars have demonstrated how contemporary understandings of childhood have emerged from specific historical developments. Indeed, historical inquiry, beginning with historian Philippe Ariès’ groundbreaking and contested work, has shown how in earlier centuries, ‘childhood’ was not conceptualised as so temporally discrete from ‘adulthood’. In Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood, Anne Higonnet tracks how this changed over the eighteenth century with the invention of the ‘romantic’ or ‘innocent’ child in Western societies. Importantly, this was an exceptionally classed development. For instance, the idea of differential clothing came in with the upper classes. Whereas children in the working class generally wore small-size versions of their parents’ clothes, amongst the elite there was the introduction of child-specific clothing, like sailor suits for young boys, over this period.

What is interesting about the invention of ideal childhood is its treatment in mediums like painting not as a shift in representation, but rather as a discovery of a natural, essential truth. As Higonnet contends, it was precisely because it was an invented idea that childhood needed consolidation through visual fictions in this way. Over the eighteenth century, one thus sees the first great movement in the visual history of childhood innocence, led by British portrait painters like Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Through their representations, these painters collectively created the idea of the innocent child.

What, exactly, is the child innocent of? The child is innocent of sexual knowledge.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the golden age of painting and illustration begins to give way to the photograph. For many years, the idea of the innocent childhood is inherited by photographers. The wide circulation of photography means, for instance, that every home can be adorned with images of mother and child. Nonetheless, over a period of time, photography began to unsettle the certainties of childhood sexual innocence. At the same time, the idea of the family as a safe haven for children began to be questioned.

With the intensification of debate around child sexual abuse in the late ’80s and early ’90s, the idea of the ideal childhood and the idea of home as a safe haven for children entered into a crisis. As the panic about harms to children, some of it real, some of it imagined, began to spread, artists and photographers came under attack.

In 1988, for example, artist Alice Sims was working on a series entitled Water Babies that involved the superimposition of photographs of her nude daughter onto photographs of water lilies; upon seeing the nude photographs, a worker at the photographic developing lab notified the police, who in turn charged Sims with interstate pornography and placed the child in a temporary foster home. Though the charges were ultimately dropped, the incident draws out how anxieties around representation were central to protecting the crisis-ridden idealisation of childhood.

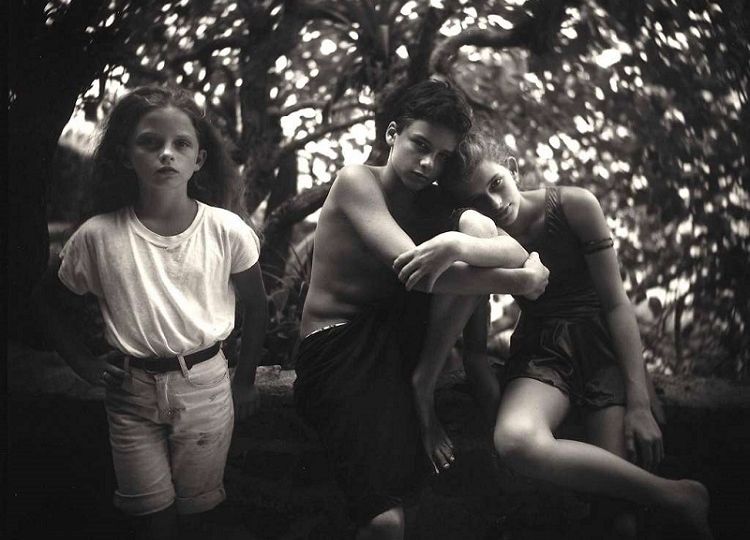

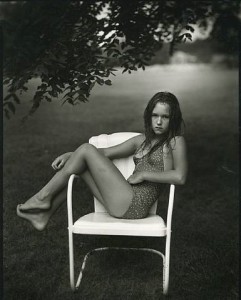

Similarly, in 1989, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs were not allowed to be exhibited because they show explicit sadomasochistic/homosexual content and exposed genitalia of children. In the public imagination, such photographs revealed the perversions of their creator. Over the 1990s, the publication of novels like Kathryn Harrison’s Exposure, which centres on the discovery of family abuse through the examination of photographs, and the passage of child pornography prevention legislation consolidated a climate wherein the interpretation of photographs was critical to claims of abuse. This climate of moral anxiety led to the targeting of famous photographers like Sally Mann, whose images – like the noted Popsicle Drips – lend to a range of interpretations.

This is a brief overview, but following the evolution and controversies surrounding the representation of the child in this way begins to denaturalise contemporary assumptions surrounding childhood. Understanding that the conceptualisation of the child as innocent (particularly of sexual knowledge) is a historically mediated representation necessarily complicates conversations around childhood and consent.

This article is one of ten essays based on presentations and discussions at the Global Dialogue on Decriminalisation, Choice and Consent, 2014.

The introduction has been written by Rupsa Mallik.

Cover image by Sally Mann from her book of photographs, Immediate Family (1992)