By China Daily

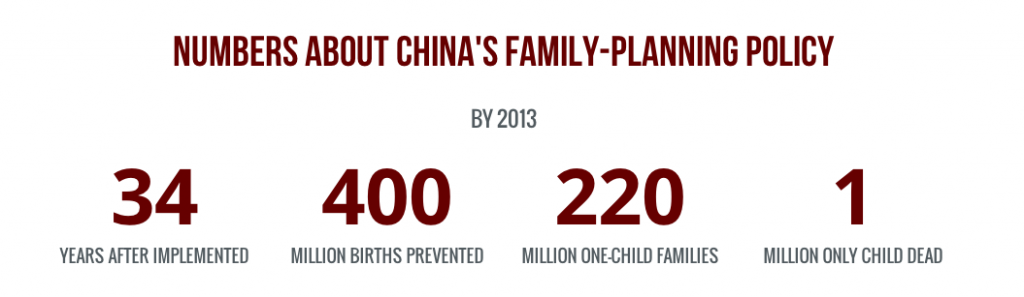

China’s family-planning policy was first introduced in the late 1970s to rein in the surging population by limiting most urban couples to one child and most rural couples to two children, if the first child born was a girl. Through 2011, according to the government, it had prevented some 400 million childbirths. But it also left bereft mothers and fathers who lost their only child to illness or an accident — and were too old to conceive again.

Parents who have lost their only child are known in China as “shidu” families. This disadvantaged and marginalized group numbers about a million and grows by 76,000 each year. This multimedia project presents the challenges they face, such as problems with finances, physical and mental health care, as well as struggles with government policies. These parents talk candidly about their stories and the efforts they’ve made to improve their lives.

The situation in China is different from that overseas. Other countries also have families who have lost an only child, but not as many. Such parents comprise just a small segment in other countries, but since family-planning is a national policy in China, this demographic group has ballooned. Among the Chinese up to 25 years old, four out of every 10,000 die for various reasons every year. This translates into 76,000 deaths each year. Over the past few decades, some 10 million families have been affected by these deaths.

— Wang Xingjuan, social psychologist

Powerful Policy:

In 1984, Zhang Tiejun, now 61, gave birth to a son. During the 1980s, the family-planning policy was strictly enforced, so she didn’t think to defy the law and have another child. In 2005, her son, then a college sophomore, died of a heart problem. This turned her life upside down.

China’s family-planning policy has limited young parents in many ways. When couples had their first baby, their employers would threaten to fire them if they had another. Most of them obeyed; they followed the government’s orders and took on the risk of becoming childless in the future.

Three decades after the policy was implemented, millions of couples have lost their only child. Some 200 million more face that risk. How can these families be compensated for their loss? How do they manage the risk of losing their only child? People are closely following recent changes to the country’s family-planning policy.

I EXPERIENCED THE “CULTURAL REVOLUTION” AND LIVED THROUGH A DIFFICULT TIME. I EVENTUALLY MARRIED AND HAD A SON, BUT THEN MY SON DIED OF A DISEASE. I THINK FATE HAS BEEN TOO CRUEL TO ME.

— Zheng Wei —

Early Life:

Fifty-year-old Zheng Wei is a retired English teacher living in Beijing’s Dongcheng district. She and her husband experienced the Great Chinese Famine and living among the peasants during the “cultural revolution” (1966-76). Their 20s were difficult. In 1973, Zheng and her husband Ren Yongmao had their first and only child.

In 1999, their son was diagnosed with malignant lymphoma. The couple tried everything to find a cure, but faced extreme financial difficulties. The young man died in 2002. Zheng and Ren had envisioned old age with their son, but their dreams were crushed.

Millions of parents who have lost their only child grew up during the 10-year “cultural revolution”. This turbulent period left them spending their teens or 20s without much purpose, so they wanted their children to experience life to the fullest. Losing their children has left many of them in despair.

I DID NOT BUY MY SON A TOMB, BECAUSE THEY SAY THAT THE OLD CANNOT BURY THE YOUNG. I DID NOT EVEN RETRIEVE HIS ASHES.

— Wu Rui —

The Loss:

After a long battle, Sun Meng succumbed to stomach cancer. Fan Xi, her mother, had only one wish: to die in her sleep and meet her daughter in heaven.

Among China’s 220 million single children, data of 1% China national population sample survey 2005 suggests that 10 million will not reach the age of 25. Remembering the death of one’s only child is agonizing. Whether the child died of a disease or in an accident, the parents’ hopes and dreams have forever been shattered.

Like Fan Xi, there are countless parents who do not want to return to the happy past — or face the bleak present. They cannot look at photographs or videos of their son or daughter and do not even want to erect a tombstone. The loss of their child has cast a shadow over the rest of their lives.

WE CAN NEVER ESCAPE THIS STATE OF MIND. FAMILIES THAT HAVEN’T EXPERIENCED THIS CAN NEVER FEEL OUR PAIN. WE TRY TO PUT ON FAKE SMILES AND PRETEND TO BE HAPPY WHEN MEETING OTHERS, BUT THAT IS NOT HOW WE REALLY FEEL.

— Zhou Zhenlong —

Mental Strain:

Born in 1979, Li Kewen majored in computer science at Peking University, one of the best universities in China. As a college junior, the brilliant young man founded his own company, which even attracted a foreign investor. Just as his career was about to take off, he died of a kidney disease in 2004 at age 24.

For the first two years after Li’s death, his mother Li A’di could not accept the loss and cried all day. She also had countless sleepless nights. Almost 10 years after Li’s death, his parents still keep his room as he left it. A decade, the couple says, cannot dull the pain of losing a child. It is a nightmare that lasts forever.

Parents who have lost their only child experience anguish that can border on mental illness. They feel empty and devoid of hope.

WHEN WE GET TOGETHER, WE OFTEN LAUGH AND CRY AT THE SAME TIME. BUT NO ONE MINDS. WE’RE LIKE BROTHERS AND SISTERS.

— Zhang Tiejun —

Parents United:

Many parents who have lost their only child cannot deal with the bereavement on their own. So they reach out and forge bonds with others who have gone through the same pain. Through the Internet, dozens of “shidu” families have met and built relationships. The parents create online memorials for their children and offer each other solace. This kind of connection gives people the chance to express their inner sorrow. Understanding brings them temporary comfort.

I WROTE MY DAUGHTER’S STORY TO COMMEMORATE HER. ALTHOUGH SHE LIVED A SHORT LIFE, I WANTED TO LET THE WHOLE WORLD KNOW THAT THIS GIRL BROUGHT IMMEASURABLE HAPPINESS TO HER FAMILY.

— Fan Xi —

Sharing Knowledge:

After the loss of her only child, Fan Xi wanted to learn more about other parents in the same situation, but she found that there were few books and other materials on the topic. So she decided to write her story.

Every dream about her daughter and every detail of her daughter’s life served as material for her book. Over countless days and nights, Fan nearly dried out her eyes from crying while writing. On Mothers’ Day 2006, she published – Once You Are Here.

The book was not only a way for a mother to deal with losing her daughter, but also an effort to offer guidance to people in the same situation. It also enabled other readers to understand the struggles of parents like Fan.

“This book is filled with my dreams, my true feelings and my memories of my dear daughter, Meng Meng. It was my idea to name it Once You Were Here, because it is simple yet clear. My friends agreed on that as well. It will be published around what would have been my daughter’s 32nd birthday, on the sixth anniversary of her death. She was once in this world, just like the rest of us. With this book, my tears and my heart, I want to tell everyone to value everything around us.”

— Once You Were Here – by Fan Xi

WHERE THE ONLY CHILD IS DISABLED OR DEAD AS A RESULT OF AN ACCIDENT, AND THE PARENTS DO NOT BEAR OR ADOPT ANOTHER CHILD, THE LOCAL PEOPLE’S GOVERNMENT SHALL PROVIDE THEM NECESSARY ASSISTANCE.

— Law of the People’s Republic of China on Population and family-planning —

— Chapter 4, Article 27 —

The Appeal:

Based on Chinese law, the rights of the elderly depend on the support of their caretakers. But many people, like Zhou Zhenlong, who have lost their only child have also lost their caretaker and source of financial support. As a result, the law on the rights of the elderly has no meaning to them. In China, where the social welfare system is not very strong, it is difficult for bereaved parents to spend their late years in a nursing home, not to mention having the money or qualifying background to live there. They are asking for a modified compensation system to provide for their twilight years.

Since they are facing a predicament without legal precedent in China, parents who have lost their only child want to see changes in the status quo. These parents have written an open letter asking for changes to China’s family-planning Law. By April 2013, some 1,804 people had signed the letter.

In May 2013, ignoring the intervention of the police and their local family-planning committees, Sun Xiaorui and at least 400 “shidu” parents journeyed to the Chinese capital to demand for their rights.

FAMILIES WHO HAVE LOST THEIR ONLY CHILD ACTUALLY GREATLY CONTRIBUTED TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FAMILY-PLANNING POLICY.

— Sun Xiaorui —

The Wait:

In May 2013, some 400 people who have lost their only child came to Beijing from all over China. They were closely watched by the Beijing police, which resulted in difficulty even with securing accommodations. The journey was full of hardship and unknowns.

On May 20, 2013, the petitioners gathered in front of the National Health and Family-planning Commission’s headquarters in Beijing to make their appeal in person. They also sent a representative to speak with an official. But the commission did not give a response that day, instead promising to address the issue before the end of 2013.

SUDDENLY THE WORLD AROUND ME BECAME QUIET. NOTHING MEANT ANYTHING TO ME ANYMORE. NOBODY WOULD HAVE ANYTHING TO DO WITH ME AS WELL.

— Chen Aiqing —

End:

At the end of 2013, the financial aid for families who have lost their only child was increased, but a policy addressing their social status and pension has not yet been released.

In the 34 years since the family-planning policy was introduced, parents who have lost their only child are still waiting in sadness and struggle.

This was originally published as an interactive feature story here in 2013