Editors’ Note: On the Ground with …. is a new feature in which we catch up with different organisations to highlight interesting experiences, intersections and insights from their work.

Maraa is an arts and media collective that was founded in 2008 in Bangalore. It was born from a sense of deep disillusionment about the ways in which the lives of people and ‘communities’ often got reduced to issues/solutions. Maraa means ‘tree’ in Kannada and it is the nature of a tree that we wish to embody, with strong roots, branches in different directions, growing tall but also wilting, dying and beginning again. We work within a horizontal structure where individuals from diverse social backgrounds can realise their ideas while consciously working toward shared political goals.

Over the years, our work has sharpened at the intersections of gender, caste, and labour, highlighting stories and experiences of violence and discrimination without losing sight of the creativity and dignity with which people fight against injustice and inequality. Our intent is to foreground experiences and narratives that are in danger of being censored and suppressed. We have consciously stayed away from defining our work as issue-based, as this has the tendency to produce silos. Rather, we have stayed true to the practice of arts and media which allows us to explore intersections, affinities and frictions, creatively, playfully and in-depth. At Maraa, we produce our own work as arts/media practitioners, collaborate with communities to encourage expression through the arts, create spaces for healing and alternate notions of justice, and support independent, community-based media. We are a small team that works with a wide range of collaborators, across geographies, languages and forms.

A journey of learning and unlearning

We began our work with gender and sexuality in the form of training and facilitation workshops. Soon, we began to feel as though there was an ‘official’ version of gender and sexuality that was often ‘taught’ to participants. We moved away from this model, using our experience with theatre and storytelling to devise modules that allowed for a conversation on gender that began with participants’ lived experiences, silences, contradictions. We worked closely with community radio journalists, students, and activists. With each interaction, we realised the vast and messy terrain that constitutes gender. As we travelled across the country, we also learned that gender cannot be viewed in isolation and that close attention needs to be paid to how it is shaped by sexuality, caste, language, religion, class and geography. This made it impossible to perceive gender as a universal, shared experience. Rather, we grew conscious that the ability to choose/express/subvert gender identities is marked by social difference.

There have been many learnings and unlearnings in the course of this journey. For example, in our work with arts and public spaces, we realised how differently the notion of ‘public’ and ‘private’ is constructed across different classes and castes. When the city was raising the question of safe public spaces, we recognised that much of this discourse was speaking to the concerns of middle- and upper-middle-class women. For working-class women, public space was their work place, and their concerns were not so much around mobility and leisure as they were around access, wages, dignity, and so on. As we worked across languages, we discovered how much of the discourse is borrowed from western frameworks of gender that positions the individual at the centre. To unlearn our own vocabularies, we delved deeper into community rituals, practices, festivals, symbols, proverbs and so on, to understand how people construct their own experiences and imaginations of gender. This has greatly enriched our own imaginations and helped us to challenge our own, often unconscious, prejudices.

Turning Points

1. Moving beyond victim/survivor | The birth of Freeda

In 2019, we were asked to document a month-long ‘yatra’ that was led by survivors of caste-based sexual violence from different parts of North India. Hearing the stories of the women we were traveling with gave us a glimpse of the systemic injustices they have faced as well as the isolation and grief the body endures in the aftermath of violence. As the people ‘documenting’, we acutely experienced the discomfort of being behind the camera and having the power to represent their stories. We also wondered if life could be so neatly divided into the binaries of being either victims or survivors. We returned with heavy heads and hearts and turned to theatre as a way of processing the residue left inside us. We worked on a performance called ‘Chu Kar Dekho’, guided by Anish Victor, which was about the body’s experience of representing, witnessing and remembering.

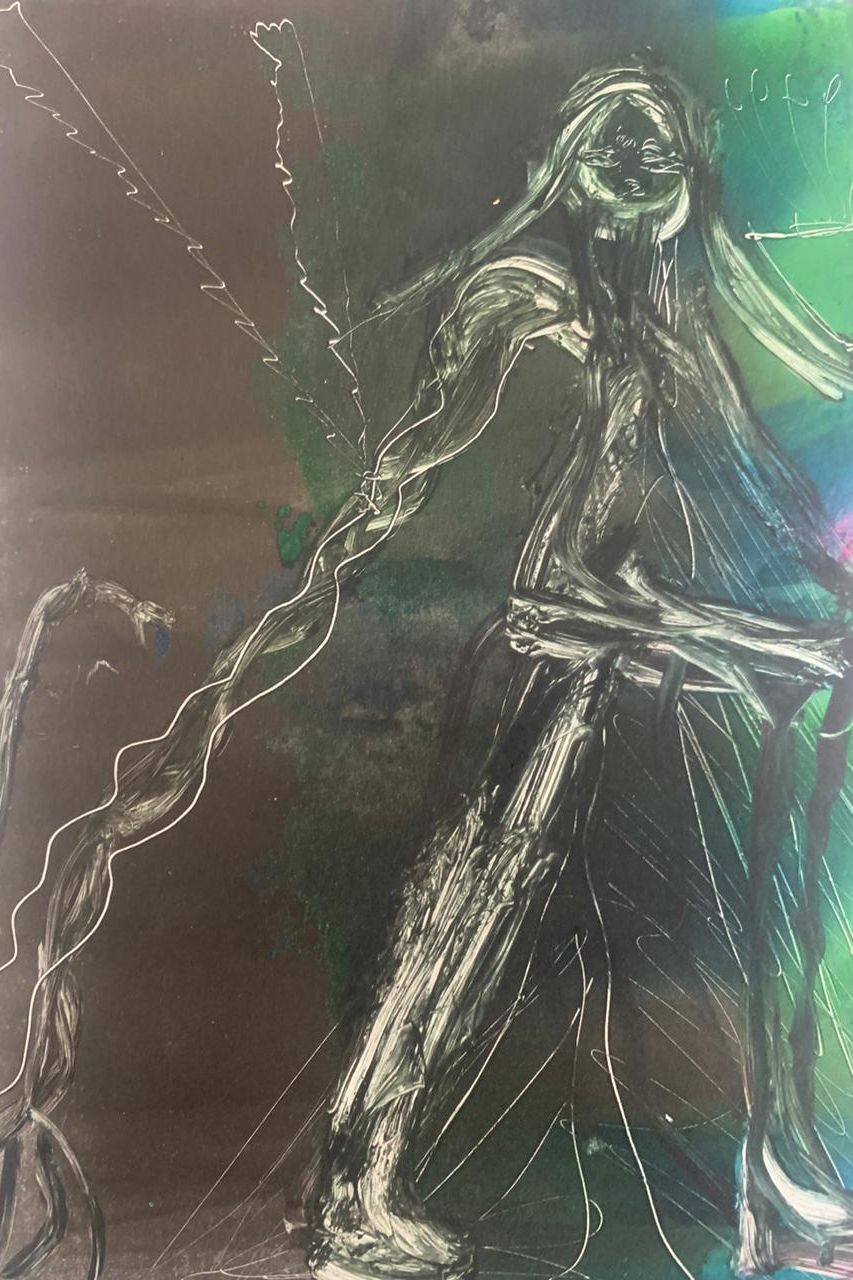

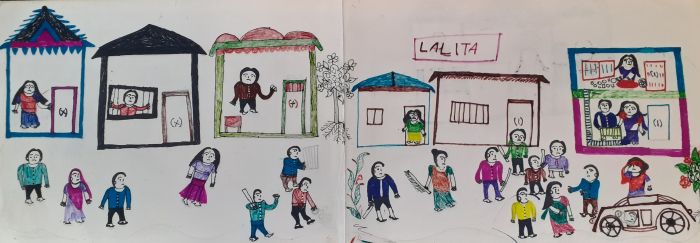

In 2021, we returned to Madhya Pradesh to share the performance with the women who had inspired its making. Having ourselves experienced transformation of body and conscience through theatre, we wished to hold this space for them too. We extended an invitation to them to embark on a theatre-making journey with us. This led to the birth of Freeda Theatre, an inter-generational collective of women from Scheduled Caste and Tribe communities in Madhya Pradesh. Having grown up in deeply feudal and patriarchal contexts, these women have endured caste-based discrimination, economic exploitation and sexual violence. The fight for justice, within the legal system as well as in their communities, has been difficult. In the aftermath of violence, the body becomes a site of shame, and the survivor finds her identity limited to the act of violence alone. In these conditions, we felt theatre could be a medium of catharsis, healing and self-representation. We worked together for nine months at the end of which we collectively devised a play, Nazar Ke Samne (Before Your Eyes), which is a collective expression of bodies that have endured caste and sexual violence. The performance is filled with unfulfilled desires, confessions, secrets and dreams. Journeying between childhood, youth and womanhood, the actors provoke questions around identity, freedom and justice.

Nazar ke Samne is woven from personal experiences of listening closely to the body to reveal beauty and violence in everyday life. The performance is centred on the body which often goes missing in the gory sensationalism that surrounds the discourse on sexual violence. For example, this is often seen in the over-emphasis on legal frameworks and the burden of ‘evidence’ which can lead to residues and fractures within the body. The performance delves deeper into the relationship between memory and forgetting, notions of justice, restriction and risk, beauty and desire. Moving away from the incident of sexual violence, it dwells on the everyday experience of alienation, desire, struggle and resilience. Nazar ke Samne has recently completed forty shows, travelling across villages and urban centres in Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Telangana. Negotiating and resisting backlash from family and community, these women have fought to move beyond the framework of being ‘survivors’ and reinvented themselves through theatre. As they often say, it is from the stage that they feel they have finally received ‘justice’. We have organised community shows specifically for women which have opened up spaces for conversation around the ideas of freedom and inter-generational differences. The play has helped to open a space which is beyond right and wrong or issue and solution, focussing rather on the body, its memory and knowledge. Moving forward, we hope to create this space for more women, such that they can take the stage to express themselves on their own terms, as well as challenge the representation of marginalised communities within artistic practice.

2. (De) construction of Masculinities

In 2022, we began working on a research study, to examine the construction of ‘masculinities’ in our everyday lives. The impulse to work on this study came from our conversations with women’s rights organisations where the scope of masculinities was often in relation to the man as a potential perpetrator or, in later programming, an ally. The necessity for this work is unquestionable, given the rate of violence against women, and the impunity that social systems and structures bestow on men. Yet, we were left with a few questions: Is masculinity universal and singular? What about the ways in which it changes due to class, caste, religious differences? Is masculinity shown only by men? And finally, is masculinity individually performed, or is it also the logic that structures and gives value to different kinds of systems (e.g., caste, religious fundamentalism and so on)?

We set out to explore these questions with twelve individuals (not formal researchers) who we invited to produce daily ethnographies of how masculinity plays out within and around them. The choice of producing ethnographies from diverse social locations was deliberate. Even though far from exhaustive, we hope that the intersections explored within the ethnographies reveal the impossibility of establishing any kind of ‘universal’ or essential masculinity/ femininity. Markers of social difference greatly impact the way in which we can express our gender, and sometimes, there is very little room for conscious choice. The study travels slowly from the self, to our families and homes, to community rituals and practices, mapping the complex and contradictory terrain of what constitutes masculinity and femininity. We believe this area of work has great potential in constructing a field of study on masculinity from a feminist perspective.

Drawing on what we have shared above, in our own journey in this area of work, we have found the most difficult aspect is to check and unlearn our own prejudices and assumptions. Our effort has been to not present ourselves as experts, but openly listen to different worldviews, remaining curious about our position in relation to the social worlds we inhabit. In the current political climate built on divisiveness and suspicion, it is crucial to find ways to engage with difference and to speak in language(s) that can appeal to a wider network of people. We strongly believe that the way in which the current right-wing government has harnessed the power of arts and culture is, in part, the reason for their continuing popularity. They have a keen understanding of the ways in which people in the subcontinent frame themselves through community practices, faith systems, rituals, festivals, mythologies and so on. Our work then, is to research and recover alternate mythologies in order to be able to create a counter-culture that can speak against violence and discrimination. Further, we believe that there is a need to shift the comfortable gaze of research/programming on only the ‘oppressed’. We believe it is necessary to reverse this gaze, to ‘write ourselves’ into our research, building on the work of anti-caste feminist scholars. We must be able to view ourselves in relation to each other in order to truly build alliances, friendships and radical empathy across caste-class-religious boundaries, as mentioned in the section above on masculinities. Drawing on the rich cultural tapestry of our country, we can search for new vocabularies, dialects, and stories that can enrich our existing imaginations of ‘empowerment’.

As we move forward in our work, our intention will be to foreground histories and narratives that are considered ‘marginal’ and to strengthen forms of cultural resistance within communities. We hope this can also go a long way in contributing to knowledge systems that are more contextual, and can be a reservoir of strength and inspiration for resistance movements and struggles.

All Image Credits: Maraa