I am fascinated by the question of how lovers reveal themselves to themselves and one another over time. In my own falling, my performance has been guided by an ideal of how I ought to be in a particular situation with a given person. On receiving validation for my play, I come to know that I haven’t failed in my falling. But does this play end? Is the performance ever abandoned? The truth revealed? Oh, it is then that the drama unfolds. Since it is easier to keep the performance going, the truth is usually buried deep within, making it inaccessible to oneself as well. Such are the ways to remain afloat. Unless, one is already on shore with Heloise and Marianne.[1]

Through the course of this piece, I am keen on exploring the ways in which the love between Heloise and Marianne lacks a patriarchal way of being (while still remaining within or inside existing power relations).[2] By ‘patriarchal’ way of being, I mean a way of being that is rooted in forms of control. Arising from a feeling of incompleteness and inadequacy, such a way of being thrives on reducing the other. In this way, by crumbling all that it touches, it tries to regain a bit more of its own worth. Such a way of being relies on words, clarifications, and explanations as a way of understanding oneself and the world. Maybe, words are important because they can be possessed and wielded in a way in which deeper feelings hardly can. The words, then, sustain control through a voice that must be heard and acknowledged. Silences, or even words with complexities in meaning, are thus rejected by this being in fear of self-loss. What is longed for, in such a world full of lack, is a love that can heal through the validation it provides. But, is the lover capable of healing without consuming the other? In such a love, there is little room for ambiguity and invention as they involve risks. As the loss of love will cause the absence of control and validation, fear underlies the ways of being in love. In the end, there can be happiness through presence and permanence. Without such permanence, what was once love becomes a tragedy, and regret becomes the predominant way of remembering it.

Only lovers inhabit this world; no poets can be found.

From the beginning of the movie, Heloise’s and Marianne’s brazenness reveal their abundance of being, despite the fact that the truth is hidden (i.e Heloise is not aware that Marianne has come to paint a portrait of her). We see it when Marianne dives into the ocean to rescue her wooden box and when Heloise runs towards the ocean after firmly treading ahead of Marianne. In these instances, the women’s behaviour denoted a non-conformity; the lack of a polite and well-mannered demeanour. We notice it when Marianne claims her food despite having just arrived (which surprises Sophie) and when Heloise requests for Marianne’s book. A straight-forwardness was established, one that did not need to wind through a twisted path of time and effort. From their step to their gaze, the two women refuse to be submissive. There are no fractures from lack, and there is no need for a cure through wooing and approving.

The first time they stand by one another, facing the ocean, each moment washes over the other with the comfort of silence. A silence sustained through equality. Although Heloise is to be occupying the role of the observed while Marianne is the observer, the former says, “We are in the same place. Exactly the same place.” There is an equality in their gaze, a gaze that isn’t possessive but curious. The roaring dialogue between the waves seems to have momentarily quenched the thirst that shines from Heloise’s ocean-blue eyes. While they steal glances at each other, like the hairs of her brush that give life to the canvas, Marianne’s deep-brown eyes emanate her desire to memorise and re-create Heloise in her memory.

Memory, we come to see, is a significant aspect of their falling. In the very first scene of the movie, the mysterious painting called The Portrait of a Lady on Fire leads us into the depths of Marianne’s memory. In another important scene, the three women read Ovid’s Orpheus and Eurydice aloud, and are fascinated by how Orpheus looks back at Eurydice on his way out of Hades, despite knowing that she will be doomed to remain in the underworld if he does. While Sophie interprets Orpheus’s actions as being unreasonable, Heloise points out how a person who is madly in love cannot resist their passion. At this point, Marianne says, “Perhaps, he made a choice. He chooses the memory of her. That is why he turns. He doesn’t make the lover’s choice, but the poet’s.” Heloise’s addition, “Perhaps she is the one who says ‘turn around’,’’ provocatively opens up the possibility of Eurydice having an equal voice in the separation that met the lovers. These thoughts reverberate through the rest of the film. On their last night together, Marianne says, “Don’t regret. Remember.”

Besides the constant crackling of fire through the movie, the burning of the unfinished portrait (that occurred the night before Marianne falls in love with Heloise) and the fire that catches Heloise’s dress (during the congregational singing that is followed by the scene on the beach where they share their first kiss) are striking moments in the developing love between the two women. They exhibit a passion that is not about butterflies. It is a love that is, quite literally, born out of the flames of fire. A burning, without which, their glances would be consumed by darkness.

It is careful glances through which the two lovers permeate each other. It is not a penetration of bodies. In intimate moments, we are titillated by the gentle stroking of an armpit. Being heavily clothed through most of the film, it is the nakedness of gestures, rather than the body, that their gaze is seduced towards. “When you are moved, you do this with your hand. And, when you are embarrassed, you bite your lips. And when you are annoyed, you do not blink. When you do not know what to say, you touch your forehead. When you lose control, you raise your eyebrows. And when you are troubled, you breathe through your mouth.”

There is a delicate fearlessness in their exploration of each other. There is nobody else who had dared to ask Heloise about her sister’s death. Despite being scared, Heloise asks, “Do all lovers feel like they are inventing something?” The sense of collaboration in their falling cannot be overlooked. The destruction of the first painting that was made without the consent and presence of Heloise is a reminder of the tangible sense of equality between the two women. It took but a single breath of reflection to wipe away a painting of many breaths; an exhibit of sacrifice prompted by a feeling of betrayal in a relationship of equality. No extended musings were necessary. We later realise how Marianne was merely preventing her own destruction by yearning for an accurate representation of Heloise.

All expectations (from the audience) to see verbose moments are flouted. When Marianne says, “I understand you,” there is no further clarification demanded. When Marianne reveals that she is a painter, Heloise simply takes a swim in the ocean. When Heloise asks Marianne how it felt to have known love, the latter offers no response. There is a graceful acceptance in such moments. After the only instance of a potential misunderstanding between the two women, tears and embraces crash over them and restore peace.

There is a sense of harmony in how the three women inhabit the cottage. In one scene, when Sophie is occupied with stitching, Heloise is cutting bread, and Marianne is pouring wine, there is an unperturbed quietness amongst them. The solidarity between the three women, visible during Sophie’s abortion, is yet another glimpse into the unquestioned support that love, in the absence of a patriarchal gaze, can exhibit.

The juxtaposition of Sophie’s body on the only bed in the abortionist’s room and the abortionist’s infant who lies next to her and intertwines his fingers with Sophie’s during the abortion caught me by surprise. My initial reaction was to pause and just marvel at the irony of the situation. Despite the powerful imagery, I was spellbound by my lack of emotional response. It made me wonder; is it not too simplistic to speak of loss in terms of happiness and sadness? In the absence of a patriarchal gaze, will we embrace the ambiguity of choice? [3] I find myself at a loss of anything but questions. Painting, as seen throughout the film, is a medium to capture such moments of raw subversion (be it the final painting of Orpheus and Eurydice or the nude self-portrait of Marianne). And with that, Marianne wields her brush as Heloise and Sophie re-enact the scene from before.

As the movie progresses, climaxes never arrive. Intimate scenes end with utterances such as “Your eyes”. Instead of the moonlit-stains that characterise moments of intercourse, we witness, for the first time, Heloise’s ocean-blue eyes as deep as night. Through Heloise’s eyes, the director Céline Sciamma forces us to transgress the colours of passion that our eyes have been accustomed to. What about the perfect end that we long for? Heloise asks Marianne, “When do we know it is finished?” “At one point, we stop,” replies Marianne.

In one of the last few scenes of the movie, Heloise calls out for Marianne to ‘turn around. As we are reminded of the scene between Orpheus and Eurydice, Marianne turns around and they share one last glimpse of each other before the scene fades. If Heloise could bring to life her re-telling of the imagined separation between Orpheus and Eurydice, can we think of the lover’s choice as being the same as the poet’s? What if love and loss are not meant to be separate? What if, by the act of turning around or its absence, the lover and the poet are left in the same place? What if the images in our memory are all that the lover and the poet can long for and possess?

“I saw her one last time.” The movie comes to an end as Marianne sees Heloise at the orchestra performance. Heloise does not see Marianne but there is a sense of an imagined presence; the memory of which evokes the uncontrollable feelings that Heloise will infinitely have for Marianne. It is a loss that has no monumental carvings and a love that continues to heal through art; through the images that can be ‘reproduced to infinity’. It is only apt that this serene movie ends without a convergence, without Heloise having to look back at Marianne or them becoming a permanent ‘one’. As the music rises to a crescendo, we are reminded of the consoling love that exists between the two women through one last gaze at Heloise’s varied expressions of happiness and sadness. Céline Sciamma has left me with nothing less than hope for a love anew. Just this one time, I would like to believe that the act of letting go can be witnessed as something other than a tragedy.

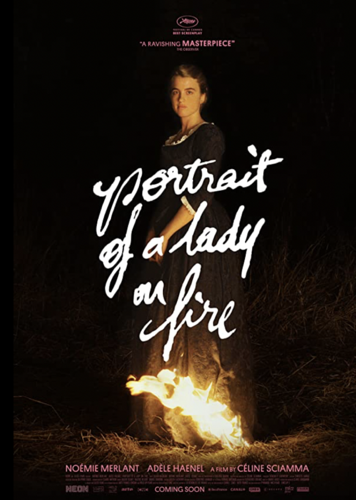

[1] Portrait of a Lady on Fire takes us to France in 1770. There, we meet Heloise, a young woman who has left the convent, and Marianne, a painter who has been commissioned to paint a wedding portrait of Heloise in secret. Confined to a house by the sea, we are met with a stillness that moves us to ponder upon the relationship between Heloise and Marianne.

[2] I must clarify that it is not my intent to necessitate that the patriarchal way of being is characteristic of any specific gender. Very often, I find myself embodying the patriarch while battling against it as well.

[3] Wherein, an abortion is not a debate between good and bad, right and wrong but an experience of queerness.