I walk into a pristine and tidy room so immaculately kept that it is hard to fathom if anybody ever inhabited this space. Yet, looking at the peppy hues of the room with shelves lined with books, VHS tapes, DVDs, and photographs, my presence almost feels like an intrusion into a very personal space. A cursory glance at the bookshelf – an entire row lined with tomes by Habermas, Deleuze, Foucault, and Spivak – reminds me of the excruciating literary theory class I took as an undergrad. In a separate rack are worn copies of films by John Cassavetes, Mike Leigh, and Lars von Trier, artists whose very presence screams incongruity in an Indian household. While an unsuspecting guest might be beguiled into mistaking this place as a personal library of a liberal arts professor, the room with all its paraphernalia is a memento maintained for Nishit Saran, a trailblazing queer filmmaker and activist who was tragically killed in a road accident more than two decades ago.

Saran, a Harvard graduate, is now perhaps best remembered for his celebrated coming-out documentary Summer In My Veins (1999), one of the earliest works of first-person queer filmmaking by an Indian artist. While his iconoclasm loomed large during his lifetime, Saran’s oeuvre as a pioneering queer filmmaker and activist seems to have been largely obliterated. Apart from selective screenings of Summer In My Veins during Pride Month or a sporadic mention of his name in an academic queer or film anthology, in our collective cultural amnesia we have glossed over one of the most incendiary voices of the generation whose legacy is as relevant as that of artists like Tom Joslin, Arthur Bressan Jr., and Marlon Riggs in articulating a political vision of gay visibility.

Born in 1976, Saran bloomed as a model Indian child – graduating as a class valedictorian from the Army Public School in Delhi and winning a scholarship to study filmmaking at the Visual and Environmental Studies Program at Harvard University. Dance practitioner and artist Mandeep Raikhy, who was Saran’s partner at the time of his death and went to the same high school as him, remembers Saran as an all-popular big star in the school. “Nishit was a name we always heard because he was the student who went to Harvard,” Mandeep recalls Saran’s mythic status during his school days as I chat with him in a café in Delhi. Continuing his streak of academic and creative excellence at Harvard, Saran won several accolades, including the prestigious Detur Book Prize for academic excellence in 1996, and was made a teaching fellow in the department after completing his degree. Filmmaker Matt Ross (dir. Frank and Lola (2016)), who was a student in the same department and Saran’s close friend, remembered him as “scary smart” and as an ardent reader. “He could talk to you about Lacan like as if he was a Ph.D. student at Frankfurt school…he was an absolute genius,” mentions an emotional Ross over a Zoom call. Amidst the intellectually stimulating social milieu at Harvard, Saran was trained in formal experimentation as well as critical theory which had a profound influence on his intellectual and creative outputs.

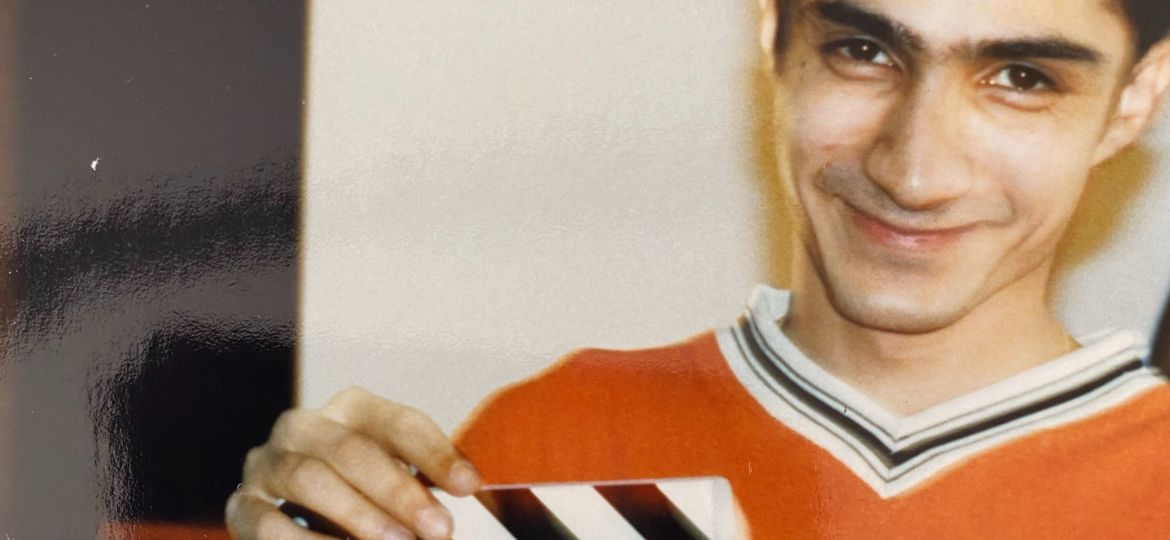

Figure 1: An early photograph of Nishit during his adolescence (Photo: Courtesy of the Saran family)

During his days at Harvard, Saran worked as a cinematographer for Ross’s thesis film Here Comes Your Man (1998) (which Ross laughingly dismisses as a reinvention of Goddard’s Contempt (1963)), and co-directed the short film Hugh (1996) with Joshua Oppenheimer (known for his Oscar-nominated films The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence in 2012 and 2014 respectively) who, in an email, remembered him as “absolutely brilliant”). Hugh, a short film about a Christian fundamentalist spewing hate towards homosexuals, encapsulated a portrait of implacable bigotry, a theme Saran would later frequent in his satirical writing on Indian politics. For his own thesis project, he decided to venture into the realm of the personal by making 50/50 (1998), a film on his mother’s breast cancer diagnosis. The equivocal title of the film toyed with the idea of her chances of making it out alive from this ordeal. Mrs. Saran, Nishit’s mother and the primary protagonist of his two films, recalls his perennial infatuation with documenting the mundanity of his family life: “Every time he came from Harvard on his breaks, he always had the camera. And he was always shooting us, shooting everyone around…” A culmination of using these domestic images and mingling them with the personal came in the form of Summer In My Veins, Saran’s most accomplished and intimate work, which he shot during his mother’s trip to the United States for his convocation.

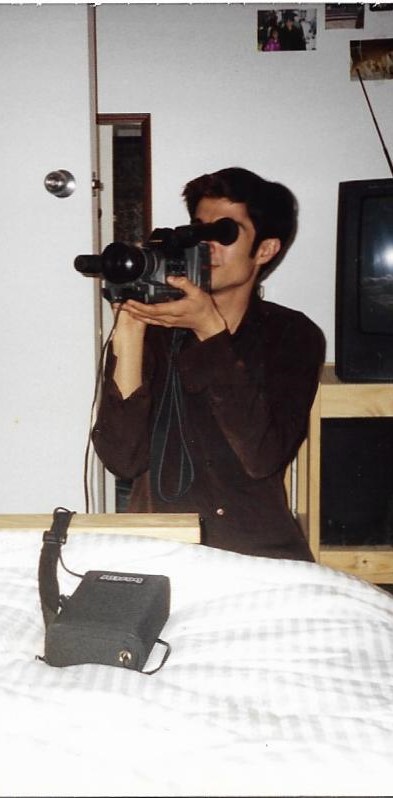

Figure 2: A snapshot clicked during the shooting of Here Comes Your Man (dir. Matt Ross),

for which Saran worked as a cinematographer. (Photo: Courtesy of Matt Ross)

On paper, Summer In My Veins is a coming-out to a parent film – a narrative that has become all too ubiquitous in our current media-saturated landscape, both in the form of fictional stories as well as personal testimonies on forums like YouTube. Using a Sony digital Handycam, Saran shot the film following his convocation on a subsequent summer trip (as the sultry title forebodes) to visit his extended family in the US. As the film commences, we see Saran dancing at his last gay party in college–his relaxed dance moves running contrapuntal to his sombre voiceover pondering about his imminent graduation. His family remains oblivious to his homosexuality, and enervated by bearing this secret, he announces his plan to come out to his mother during her trip. As the narrative progresses, Saran discloses that not too long ago, he had an unprotected sexual encounter with an HIV-positive man and fears that he might have contracted the virus. The looming shadow of testing positive has made his coming out more urgent. Following a tense journey full of hesitations, he finally comes out to his mother and receives her unwavering support. The film ends with Saran receiving his blood test report and jubilantly smiling with relief over testing negative for the virus.

Apart from its personal story of coming out (which bears a likeness to Tom Joslin’s remarkable Blackstar: Autobiography of a Close Friend (1977)), Summer In My Veins navigates how love, sexuality, and intimacy are both subscribed to and deconstructed within a South Asian family setting. In a road trip car sequence early on, Saran films his mother and aunt singing a lullaby about a mother wanting her son to bring home a beautiful bride signalling the ways in which families orient their children towards heteronormativity. Later, Saran’s camera focuses on the entire family at home, watching the Hindi romantic drama Pyaar Kiya Toh Darna Kya (1998), the dance sequence between actors Kajol and Salman Khan again bringing back the inevitable traditional alliance of a man and a woman so vehemently hammered home by mainstream Indian cinema. However, despite these moments, Saran’s genius lies in subverting the conventional depictions of Indian families as sexually conservative and prudish–an all too hackneyed trope. By constantly showcasing the raunchy repartee between his mother and garrulous aunts, he undercuts the puritanical depiction of South Asians by framing his desi family as a space where sexuality is playfully discussed, jokes are cracked about lotions functioning as lubes, and the likeness of a banana or a sausage to a phallus is not lost. Moreover, in one of the more solemn sequences, Saran films the women of his family engaging in a discussion about queer issues. While one aunt purports homosexuality to be just a phase, Nishit’s mother and other aunt express scepticism and believe it to be an innate part of one’s identity. Saran’s punctuative use of these moments amidst his own personal story opens up the space to ponder and queer the otherwise conservative familial space that lends the film its distinctive radical appeal.

While this dexterous exploration of the dichotomy between the self and the familial certainly elevates Summer In My Veins above its rudimentary classification as a coming-out film, the paratextual history of the documentary further underscores its relevance in articulating a vision of queer politics beyond the self. By coming out not just to his mother but also to the rest of the world, Saran challenges the charge against first-person documentary as a merely solipsistic endeavour. This was also during a time when homosexuality was criminalized under the draconian Section 377 of the Indian penal code, and queerness was frequently denounced as a Western aberration– something all too apparent during the massive backlash to Deepa Mehta’s film Fire in 1998. Saran, returning from a liberal and accepting social milieu at Harvard, noted the worrying lack of open and out queer people in India and the problematics of staying in the closet in those tumultuous times. In his essay “Where Are All The Gay People?” Saran deemed coming out as a moral imperative, arguing, “Revolutions need faces; people need people to look up to”. Summer In My Veins thus became a pedagogic medium via which Saran could contribute to a project of visible gay politics in a nation oblivious to queer people.

Figure 3: Saran with a camera in one of his dorm rooms. (Photo: Courtesy of the Saran family)

The Indian release of the film in various art circuits and festivals made the convivial Saran a local celebrity in Delhi. “The film screening was a shock. There was not a single paper, a single magazine which was not covering it,” says Mrs. Saran, detailing the innumerable clippings she saved during the time. Saran continued to screen the film in academic institutes in Delhi as a means to gather support for a latent queer movement. Alongside his activism, he worked on several projects, including his feature film A Perfect Day, an experimental romance that premiered at various local festivals, and Project Flower, a documentary about children living in Delhi’s slums. However, his most relevant contributions during this period came from his iconoclastic writings that were published as op-eds and columns in various journals and newspapers. Compiled posthumously as Lurkings in 2008, the acerbic essays took jibes at chauvinistic politics, media figures, and the gloating state of documentary filmmaking in the country. Their satirical nature, however, did not negate Saran’s intersectional politics that cogently called out social inequities and middle-class smugness. In “Why My Bedroom Habits Are Your Business,” his polemic against Section 377, he castigated liberal complacency, which ignored the harsh lived realities of queer people under an archaic and oppressive law; while his open letter addressed to then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee called out the government for carrying out the infamous homophobic police raid at two HIV/AIDS NGOs in Lucknow. Further, despite his upper-middle-class standing, he envisioned an egalitarian gay politics that did not negate lesbians, trans people, and working-class folks – articulating an emancipatory world for all subaltern groups in his writings. Editing being his major passion, Saran also co-edited the short film Sum Total (2000) by filmmaker Sonali Gulati about a queer woman’s matrimonial ad running contrary to the coy figure of Indian womanhood. The discomfort regarding heteronormative expectations was a recurring concern in his own work as well.

Apart from the critical success of his works, Saran also gained much social currency in Delhi, thanks in large part to his gregarious nature. “Nishit was a social magnet – everyone wanted to know him, and he wanted to know everyone…” Raikhy recalls Saran’s overtly extroverted personality that made him the darling of everyone who came into his circle—this diverse array of experience further bearing an influence on his eclectic writings. Continuing on his versatile path, Saran began directing At Home In The World, a poetic filmed account of the first International Festival of Indian Literature. This turned out to be his final project as on the unfortunate night of 24th April 2002, Saran, just shy of his twenty-sixth birthday, was killed alongside four of his friends when a speeding truck rammed into their car. At Home In The World was posthumously dedicated to his memory. In his autobiography, author and activist Sharif Rangnekar remembers being dumbfounded by hearing the news of Saran’s passing, “The gay community, I recollect, was stunned. Nishit was not just an activist but also an icon to many… Several of us gathered that weekend and talked about his sudden death, his contribution to the movement, and what it was to come out and live in India where even urban, so-called progressive societies were nothing but regressive”.

Since his passing two decades ago, the LGBTQIA+ movement in India has undergone a sea change. Section 377, the tyrannical law against which Saran actively wrote during his lifetime, was ultimately read down in the historic 2018 judgment by the Indian Supreme Court to exclude from its ambit adult consensual same-sex acts. However, queer history being as ephemeral as its subjects seems to have rendered Saran and his legacy into oblivion. Most of his films remain out of public reach, and a select few are either relegated to academic institutions or are to be found in fragments over the Internet. Unless you’re lucky enough to have grabbed hold of a copy of Lurkings, most of his perspicacious works also elude an interested public. This negation in the form of inaccessibility does a great disservice to one of the most polemic voices of his times. Despite his pioneering efforts, Saran’s works have barely received any general or scholarly attention. Perhaps the most fitting tribute to his legacy came in the form of Queen Size (2016), a dance performance piece by Mandeep Raikhy. Inspired by Saran’s essay “Why My Bedroom Habits Are Your Business,” it invited its audience into the bedroom with two male performers staging dance steps echoing various sex positions. The voyeuristic nature of viewing this intimacy incarnated Saran’s commentary about the government’s intrusion into the private lives of its gay citizens.

Saran’s sophisticated (but never self-centered) films were perhaps one of the early precedents of first-person filmmaking in the country, a form later perfected by artists like Saba Dewan and Avijit Mukul Kishore in their respective works. “He used film as a form of self-exploration, which is an incredibly brave thing to do, especially if you are coming to terms with your sexuality. And to do that in a sort of public format, it was fascinating and incredibly courageous too…” Ross says, lauding Saran’s intrepidness as an out-filmmaker during a time when queerness was, at best, a clandestine affair in India. By epitomizing the uncomfortable paradox that queer individuals need to be out and rebel to enjoy a private life, Saran’s radical works laid bare the plain and naked truth of queer life: the personal cannot be anything but political.

Notes

Saran’s film Summer In My Veins is now available for viewing online. I am also up for answering any queries about Nishit Saran or accessing any of his writings/works. I want to thank the following people who aided me in this project: Dr. Akhil Katyal (for encouraging me to undertake this project in the first place and for lending me his copy of Lurkings), Mandeep Raikhy (for his generosity towards this project and for being the constant bridge between Nishit’s family and me), the Saran family (who gave me their time and allowed me access to Nishit’s personal belongings), filmmaker Matt Ross (who devoted time from his busy schedule to talk about his friendship with Nish at Harvard), and Dr. Vebhuti Duggal (who provided crucial insights on accessing analogue archives and restoring them).

References

- Saran, N. (2008). Lurkings. The Nishit Saran Foundation.

- Rangnekar, S. (2019) Straight To Normal: My Life As A Gay Man. Rupa Publications.

Cover Image: Courtesy of the Saran family