I share an apartment with two friends in a cramped street across from posh, climber-draped bungalows in South Delhi. All three of us are young women who have recently stepped into adulthood, and its unfortunately timed pipe leaks and relieving pay days. All our neighbours, next-door and three streets away, know (and sometimes unwittingly discuss in our presence) a few things about us: we smoke and/or drink, many men visit us, and at times, leave the following morning, and we come and go at odd hours. Simply put, we could feature in a stock photo of ‘liberal’ women.

On a hot day in February when we travelled in the Metro, breathing and sweating freely on our fellow passengers, to offices where we sat for eight hours, our landlord’s brother called me, giddy-drunk, and said he was at our doorstep to deliver a gift. Dread gripped me: I called my flatmate who was home at the time and asked her if she was safe, we prepared for all worst-case scenarios as she double-checked the lock on the door and looked out of the peephole. On the wooden ledge beside our staircase was a small lumpy polythene bag. Ten minutes later, our landlord called profusely apologetic, informing us the bag contained a packet of cigarettes. This made it clear to us that despite all our everyday struggles and joys in learning how to ‘adult’, where we live, we will always be ‘that type of girl’.

As I spend more time away from home, much to my mother’s glee (of the I-told-you-so variety) I agree with her more. Snatches of her saying, “We forget we are women first when we start to entirely fend for ourselves but the world rudely reminds us” wiggle their way into my head during incidents like these. In Zami, Audre Lorde poses the question: “To whom do I owe the woman I have become?” We become women before we become a woman. Of course, we don’t need to try hard to do so, a Harry Potter-like hat sorts us into different types, robes representing each, which we wear while performing: the good/bad girl, the slut/prude, the cool girl, the quirky girl, and so on. We learn the sides and folds of the gendered box we are in before we gain the perspective to decide we don’t fit in and build a customised box or choose to have no box at all.

Growing up as I did in the early 2000s, ‘liberal’ women we saw on-screen and read about weren’t discussed beyond the bubble-wrap casing of the box in which they were put. Iconic characters like Poo from Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (who is now a queer icon) and films about women such as Aisha and Veere Di Wedding didn’t unpack ‘liberal’ enough for us to understand what the box holds. Are we liberal because we smoke/drink/have sex – broadly, tread in traditionally men-only territories and take up more space than is allotted to women – or do we exercise our agency in living the way we do because we are liberal and, of course, privileged? We were taught to identify such women by certain markers: too-short skirt, make-up, cocktail glass in one hand, cigarette in the other, and in the company of fawning men.

At school, we were cautioned against wearing skirts above the knee and socks below the ankle. Older, sex is as much a part of our life as buying Harpic every other month, although an infinitely more enjoyable process towards a similarly satisfying outcome. At the same time, we have difficult conversations with ourselves and those around us about who we are, who and how we desire or that we do not, and who we want to become. Often, more difficult than these conversations is navigating the space we occupy, between the world we as feminists want it to be and the world as it is.

The other becoming, as it unfolds in Audre Lorde’s Zami is just that: becoming. As a twenty-four-year-old woman, the personal of the political is confoundingly and exhilaratingly open-ended. We can make our own choices, and we also wonder how much they are influenced by our socio-economic and political context. We can identify, love and explore the private and the public as we want, and we also tackle the very un-theoretical implications they have on our daily life and conduct, relationships, political classification, safety and rights.

Central to exploring my sexuality has been an unlearning process. A rabbit hole with a ton of reading and no mad tea parties. Many times, I stumble in the middle of a sentence “men and women – er – people of all genders”, or recall a childhood incident and try to relate it to my present perspective, or feel uncomfortable about feeling uncomfortable with armpit hair. These have followed far more troubled waters: falling in love with a woman and its disorientation, trying to have sex for the first time, calling my friend and asking, “Where does it go?” (which has since become a response to life’s every unsolved mystery: loose change, unrequited love, a tub of ice-cream, forgotten memory, “My pen!”) because it possibly couldn’t hurt that much, having sex and feeling guilty and/or ashamed, wondering during a hook-up if I wanted to ‘go further’.

As we venture deeper into the world as grown-ish ups, we are trying to reconcile with learning as well as unlearning, neither of which has a clear finish line. We ‘mind the gap’ and work within it: a task as frustrating as it is rewarding, and find ways to cultivate safe and inclusive spaces for ourselves and others, especially those different from us in their choices and expression. We stay on our toes to keep up with and hold space for more and more strands and nuances in our perspective and work. Most importantly, we reassure each other and by extension our own selves that even if who we are is outside of the norm, we are accepted and loved.

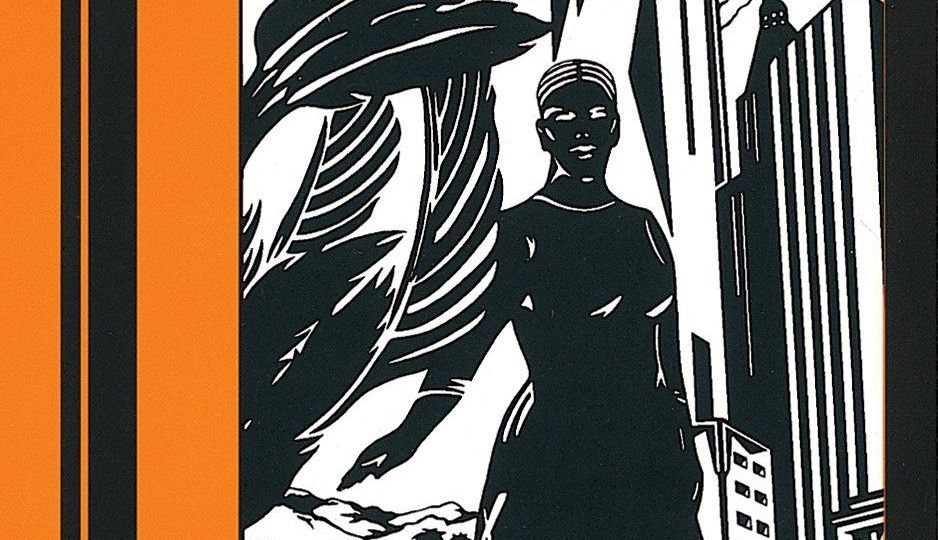

Cover Image: Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lord