Earlier this year, Saba Mahmood, an anthropologist of Islam and feminism at the University of California, Berkeley, passed away. I never had the pleasure of meeting Prof. Mahmood. I know her only through her work. In particular her book Politics of Piety: Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject (2004) makes challenges and advances existing feminist scholarship on agency, embodiment and religious subjectivity. Mahmood swims against the current in both anthropology and feminism to examine the liberalist presuppositions that locate feminist agency in acts of resistance and subversion alone, and suggests instead that feminist agency also be located in acts of submission. This article is an attempt to think about the female/queer religious subject in the Indian subcontinent with Mahmood’s brilliant writing on agency. I do so by examining two poets of the Lingayat[1] movement in the 12th century: Akka Mahadevi and Basavanna.

I thank my friend Ferhan Guloglu for reading this in advance and for her generous comments.

People,

male and female,

blush when a cloth covering their shame

comes loose

When the lord of lives

lives drowned without a face

in the world, how can you be modest?

When all the world is the eye of the lord,

onlooking everywhere, what can you

cover and conceal?

– Akka Mahadevi, translator, unknown

Remember those afternoon movies on Doordharshan in the 1980s? I can’t speak for everywhere, but in Tamil Nadu, we could tune into movies made in ‘regional languages’ other than Tamil, once in a while. I was not allowed to watch movies back then, and so over the two- three hour period, I slowly sauntered in and out of the living room many times, gleaning as much of the movie as I could. One afternoon, thanks to such stealth, I came across a movie about a woman who decided to take her clothes off, throw them in her leery husband’s face, and walk out of his home covered in nothing but the long tresses of her hair. Through some careful lingering, I gathered that she tore her clothes off because she could not stand her husband’s longing for and obsession with her body. Instead, she shamed him by profaning herself deliberately, and declared her love for Chenna Mallikarjuna (which I later learned was one of Shiva’s names). I don’t remember seeing –or gleaning – anything more. My guess is that I was asked to leave and stay in my room until the movie was over.

Akka Mahadevi’s story is a collectively produced local legend. There are no historical records to trace who she really was, if she was really married, if her act of disrobing was done in defiance of her husband’s obsession with her body. But that is how the story gets told. Her poetry declares her desire to unite sexually, emotionally and spiritually with Chenna Mallikarjuna. Mortal men seem like distractions she prefers to live without:

Husband inside, lover outside.

I can’t manage them both.

This world and that other, cannot manage them both.

Akka Mahadevi always felt like a feminist icon. In the 12th century Lingayat movement dominated by men, here was a woman titled “akka”: a sign that her arguments, teachings, and thoughts were highly respected within the movement. Her story – one in which she walks away from home, marriage and family – has lived on. Can her actions be seen as being defiant of social norms? Did her love for a god – and not another mortal man – allow her to subvert patriarchal norms, and walk away from a husband she was not interested in? But then in more recent times, I’ve wondered if there is another way to examine who she became by centering her love for Chenna Mallikarjuna rather than her defiance? She walked away, yes. But she walked into something she really deemed worthy of her trust, her care, and her love. How does one understand this?

Here is another poem that begs the same question: is this defiance or something else?

Look here, dear fellow:

I wear these men’s clothes only for you.

Sometimes I am man. Sometimes I am woman.

Oh Lord of the meeting rivers

I’ll make war for you

but I’ll be your devotees’ bride.

– Basavanna, translated by A.K. Ramanujam, Speaking of Siva (1973)

When I first read this vacana (understood to be spontaneously uttered poetry), I was a little awestruck at the poet’s ability to propose in one sentence war and erotic love in the name of Shiva. Here was a male poet ready to draw blood to protect his devotion and ready to unite sexually with the lord (or a male devotee). A.K. Ramanujam notes, in the preface to his translation that the militancy that animated the Vira-shaivya movement often produced poetry that questioned the role of gender and gave way to bisexual expressions. Additionally, he writes that this movement was a deliberate move away from Sankritisation. The poems were spoken and shared in Kannada, and did not require the listener to be literate or have any form of textual knowledge. Thus, not only did the movement defy hetero patriarchy, but it also resisted caste-based hierarchies by calling forth people from all castes to join in the production and circulation of these vacanas.

Again, however, can the agency of this movement only be understood in locating agency in resistance? Is the Lingayat movement a social movement that primarily aimed to resist gender norms and caste hierarchies and used Shiva as nothing but a medium to that end? But if one were to centralise the figure of Shiva, then how does one explain the desire and pleasure that ebb and flow through the verses of poems written by the adherents of the Lingayat movement? How does one explain the awkward relationship between feminist agency and religious subjects, especially in a time when religion is often evoked only to put all non-heteropatriarchal ideals to bed?

Here is where a reading of Saba Mahmood’s Politics of Piety provides an interesting way to look at the agency of religious subjects like Akka Mahadevi and Basavanna. In her ethnography, Mahmood traces how the gendered lives of women who belonged to the Islamic revivalist movement in Egypt during the 1990s are shaped by their attempts to live by their understanding of the teachings of the Koran and the hadith. The women she talks to in her book organise their own reading groups in Mosques to learn and interpret the Koran and the hadith. In doing so, large numbers of women begin to occupy spaces that were previously accessible only to figures of authority, most of whom are men. However, Mahmood reminds her readers that their interest in forming reading groups is centered around the desire to become devout Muslims, and to submit to the transcendental will of God. Thus, these women wilfully subordinate their free will, and strive to “pursue practices and ideals embedded within a tradition that has historically accorded women a subordinate status” (Mahmood 2004, p5). For example, to become and remain a good Muslim, women would have had to strictly follow certain norms about veiling, marriage, family – all of which have been points of contention across the world for Muslim women and the feminist movement at large. In other words, it is one thing to sing “Pardeh main rehne do” (Let me remain behind the veil) while playing antakshari (a game of songs) with friends, and another thing to remain in a Pardah, in a world that idolises the lipstick under the burkha, and constantly looks for at least a clandestine sign of defiance from the veiled woman.

As Mahmood notes, this search for defiance comes from the close ties between feminism and secular-liberalism, both of which centralise emancipation, and locate freedom only in acts of resistance. Thus submission is overlooked. It becomes a little hard for those of us approaching feminism from a mandatory emphasis either on resistance or on subversion to understand that adhering to norms of modesty can, in fact, be the key to realising one’s potential and possibilities for action as a gendered subject. In other words, when there seems to be a universal agreement that feminism is feminism only when there is intentional resistance or subversion of gender norms, it seems almost counter intuitive that the woman who genuinely desires and pursues these norms can be a self-realised subject. But that is what Mahmood found: her interlocutors were only able to become self-realised female subjects as long as they lived by the norms. Subverting them or resisting them did not feel emancipatory and laudatory, but rather like failure.

What Mahmood calls for is not a redefinition of feminism and patriarchy. But, she does call for a re-examination of the centrality of emancipation in the feminist goal for self-realisation, and thus, an expansion of the way feminist agency is conceived. Rather than locate all of patriarchy in religion, and then examine how feminist subjects struggle against the tide of religious patriarchy, Mahmood examines how the adherence to religion and the norms it outlines, allows the devout female religious subject to overcome patriarchal barriers in order to become fully realised gendered and religious subjects (such as form women’s reading groups). Here, it is important to note that these women do not primarily intend to resist or challenge patriarchal barriers, but to affirm their subordination to the will of God. It is their interpretation of the will of God that makes it possible for them to become actors in historically male-dominated spaces and perform tasks previously performed mostly by men. Such self-realisation, Mahmood says happens within historically specific conditions: the historicity of the mosque movement she studies allows women to experience self-realisation in a non-emancipatory discourse of submission. Thus, at the heart of Mahmood’s discussion is a call for historically specific feminist readings of agency, rather than a universal reading that assumes that emancipation must be at the heart of all seemingly feminist acts.

Hence, my turn to 12th century Bhakti poetry in this essay, in order to bring Mahmood’s embedding of feminist agency in submission to religiosity in the Indian subcontinent. Emancipation as we know it is not a 12th century construct, and to read it into Akka Mahadevi’s life or the life of Basavanna, would be a faux pas. And yet, it is not uncommon,if one does an Internet search,to find the erotic poems of the Bhakti movement appropriated into feminist discourses that centralise emancipation. If it is not emancipation but adherence that is centralised in discussions on the Bhakti movement, then it is very possible that the poem has been desexualised with some vague explanation about spiritual rather than sexual desire and pleasure, and appropriated into some right-leaning conversation on sanskari India, before colonialism. But Mahmood’s ability to locate agency in adherence and in self-realisation, without necessarily locating it in freedom and emancipation provides another way: it is very possible that acts which seem resistant and subversive now, were in fact acts of submission. Take Akka Mahadevi. She expresses her love for Shiva not as an adulterous woman defying marriage but as a woman claiming to want only Shiva as her marital and sexual partner. It is because she wishes to live as the wife and lover of Chenna Mallikarjuna that she denies the need for a mortal husband. In fact, it is as the beloved of her immortal male lover that she gains access into male-dominated courts for debates that then bestow on her the title “Akka”. Sexual desire and the pleasure that comes from it are not born from fighting against presupposed repression in religion, but from submitting to and exploring other possibilities of being within the religious discourse. Reading Akka’s poems away from a repression/emancipation framework asks us if repression is intrinsic to religion, or if religion has been saddled with repression because of our own political presuppositions. Similarly, take Basavanna: his expression of gender queerness and bisexuality is only non-normative as much as it is normative: he becomes a woman sometimes, to wed a man; a man sometimes to wage war, locating femininity at home and masculinity on the battlefield. What is non-normative here is that a single body is allowed to cross these thresholds and become both male and female, depending on the space it occupies, as long as it is done for the love of and desire for Shiva. Again, defying caste and gender barriers is not the intended act; rather in affirming an undying love for Shiva, caste and gender norms seem to loosen their hold within Basavanna’s poetry.Thus, as he formulates norms for the Lingayat movement, he centralises piety and organises it around the figure of Shiva and decentralises caste and gender, which may have been central for other forms of worship at that time. It works more like a reformatory movement, but without liberalist underpinnings.

There are several differences between Mahmood’s reading of agency and what I am trying to do here. Her work examines a movement now, mine, a more historical one. Her work examines a discourse that centres texts such as the Koran and the hadith; I try to explore a movement that deviated from textual interpretation. But what I want to show here is that agency is not always linked to identifying, problematising and then becoming emancipated from repression. Such a framework can only narrate the history of all bodies that do not conform to hetero patriarchy as bodies produced within repressive frameworks. These bodies then need to recognise their own repression and break free from it either by deliberately resisting the norms to which they are subject, or by accidentally failing to live up to them and thus, subverting them. But Mahmood suggests that we do not read our histories as a history of repression. By taking this idea to this historical piety movement in the Indian subcontinent, I want to suggest that Bhakti need not be read either as an articulation of protest against existing norms, nor as a repressive movement where all things sexual had to be hidden under the banner of spirituality. Bodies that submit to the norms of the Lingayat are not bodies bereft of desire and sensual pleasure. Rather, the act of submitting to Shiva allows them to experience desire, sexual pleasure and rapture in ways that are not available to those who do not submit to these norms.

What does this decoupling of emancipation from feminism mean for a study of agency in the Indian subcontinent today, particularly in the context of religion? In India, there is a long tradition of writing off religion as a pre-modern, pre-political mode of engagement with the world: while this tradition was born in an attempt to resist Orientalist stereotypes of the Indian subcontinent, where objects, people, and places seemed steeped in a historical mysticism, this tradition seemed to make religion seem like nothing but a barrier to progress and modernity. Subaltern scholarship has written against this dismissal of religion as a pre-political discourse, arguing that peasant politics which was elementary in the freedom struggle was often shaped by its adherence to and belief in religious discourses (Guha and Spivak, 1988). However, it is not uncommon for religion to be dismissed both in feminist activism and scholarship as a backward, pre-political discourse which leads to nothing but repression. Especially at a time where fascism seems to be rearing its head across the world, it is very easy to become so wary of religion, that any adherence to it begins to feel to a non-religious observer like the result of brainwashing and a false consciousness. In my own personal experience working with non-profits, I’ve come across – and also believed – the notion that adherence to religion is often the result of the lack of education, and that a deliverance from religion is necessary for feminist self-realisation. Often this results in projects led by ‘experts’ from urban areas (and often from other countries) ‘teaching’ rural women about how to better their lives, without bothering to listen to what might actually make their lives feel better. Problems with this framework are twofold: it reinforces the notion not only among urban social workers and activists but also among rural women (see Ram 2013, Pandian 2009) that the latter are indeed backward and in need of saving. It also re-inscribes a teleology: there is one way to progress and that way comes from accepting a liberalist-secular framework unconditionally. Such teleologies mask unexplored possibilities within religious frameworks that instead of working against secular-liberal frameworks, might be able to provide an alternative that exists beside it.

What one learns through the work of Saba Mahmood is the necessity to re-examine the underpinnings of our own politics and our unquestioning adherence to the repression/emancipation binary. Not all religion is fascist, and not all adherents to religion are repressed, stuck, and in need of rescue. Self-realisation can come in many forms, and if agency is about coming into the self, and recognising one’s capacity for action, then agency depends on the historic conditions that one inhabits. Since all women do not share a common history, agency cannot and need not be located for all in an emancipatory discourse and in the recourse to resistance and subversion. For some, feminist agency and the realisation of one’s potential as gendered actors in the world can come from submitting to a discourse that others deem repressive.

***

Bibliography:

Guha, Ranajit and Spivak, Gayathri. 1988. Selected Subaltern Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mahmood, Saba. 2004. Politics of Piety: Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: University of Princeton Press.

Pandian, Anand. 2009. Crooked Stalks: Cultivating Virtue in South India. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press.

Ram, Kalpana. 2013. Fertile Disorder: Spirit Possession and its Provocation of the Modern. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Ramanujam, AttipateKrishnaswami. 1973. Speaking of Siva. Middlesex: Penguin Books.

[1] Lingayat can refer either to a movement or to a community that was organised around the figure of Shiva in Karnataka between the 12th and the 18th century. Today, the Lingayat movement is believed to be a sect of Hinduism (Ramanujam 1973), because of its overlaps with other Hindu movements of the time. However at varying points in time, the monotheist visions of Lingayat poets and scholars which considered Shiva to be the one true god could have contradicted polytheistic and animist views held by other Shaivite, Vaishnavite and Tantric practitioners of the time. Often the Lingayat movement is also called the Veerashaivya movement, though some believe that the latter is a much more widely accepted philosophy that predates the formation of Lingayat communities.

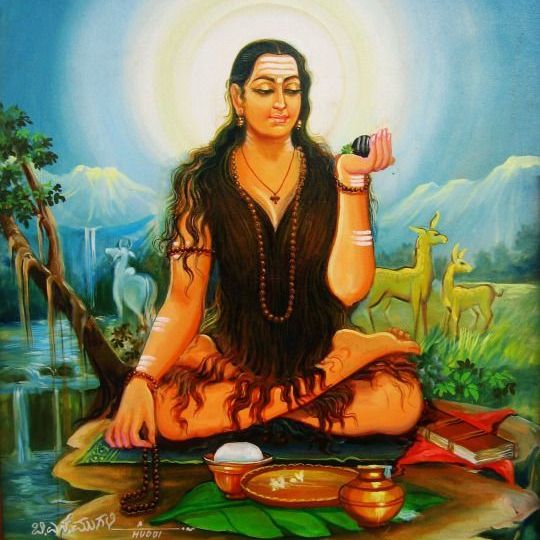

Cover Image: Pinterest