“For some, it is the azhaan (the Muslim call to prayer) that speaks to their hearts, for others, it is the suprabhaatam (a Hindu hymn to the deity Venkateswara). To me, the beauty of god can never be summarised with only words,” muses Saboor, the queer, gender fluid protagonist of the webcomic Puu, in a scene where the story flashes back to his[1] teenage years. While stumbling upon this epiphany, he is caressing a butterfly (drawn in vivid colour in an otherwise black-and-white panel), witnessing the miracle of its flight. And through it, he is experiencing an intense spiritual moment – as if being in touch with a harmonious truth beyond the self, beyond simply the domain of faith or rituals (though, in the story, faith is equally important to Saboor).

Like many things in Puu, the butterfly becomes symbolic – of spiritual harmony, of belongingness, of a deeper connection. Of freedom, for young Saboor, who, born into an upper-caste Brahmin family, has been plagued by the blatant homophobia he has experienced all through his childhood. Through the butterfly, Saboor realises that the ‘beauty of god’ does not need to be associated with a religious conservatism that hinders the expression of his sexuality and of his true self; that it can be something bigger, something he can interpret in his own way. At the end of the day, it is Saboor’s endless capacity to love that connects him to a higher power. It is his endless sense of compassion that ties him to his faith and to spirituality.

Puu, an episodic comic (consisting of 92 serialised episodes) created in 2016 by Nabigal-Nayagam Haider Ali – going by Nabi online – is woven together with vast, expansive threads of similar intense spiritual moments and reflections on devotion, faith, and love. Even when exploring themes like that of identity, sexuality, gender, caste, and religion, this sense of a transcendental form of connection, of experiencing something beyond oneself, is omnipresent. Set in modern-day Chennai, the story revolves around Saboor and Jameel, two queer Muslims who fall in love while living together as roommates. Parallel to their story runs that of Mukhil, a dalit transwoman engaged in politics and contesting local elections; Noor, a niqaab-wearing lesbian Muslim lawyer fighting for the rights of other queer couples, and her lover Alamelu, who, despite being queer, has had to marry a man for her own protection, but ends up sharing a healthy platonic relationship with him (to the point that he is extremely supportive of her sexuality and her relationship with Noor).

Each character’s trajectory is mapped through the intermingling of their sexual or gender identity with their faith or spiritual beliefs. As mentioned earlier, Saboor had struggled with the extreme homophobia he experienced within his family in the name of religion, but, inspired by a shrine of Thulukka Nachiyar (a Muslim princess who had married Vishnu, a Hindu deity, and had later become a revered Hindu saint), symbolic of the fact that religion need not be linked to fundamentalism, Saboor could find the courage to run away from his emotionally abusive home and forge an independent, queer, Muslim identity inspired by theosophical sufi doctrines. Jameel, who is a transman, also struggled with the transphobia and homophobia of his conservative Muslim father as a kid, but his steadfastly supportive mother always stuck by his side and raised him with a great deal of compassion. Hence, Jameel’s relationship with faith and spirituality comes with connotations of love, warmth and kindness. Jameel is also a bharatnatyam dancer, which is interesting, because it too is a dance form often used to convey spiritual ideas – and it is when Saboor sees Jameel perform bharatnatyam for the first time, that he experiences an overwhelming sense of longing and attraction towards Jameel.

Mukhil was abandoned as a child for being trans, and, though having faced marginalisation for her gender and caste identity, she still goes on to win a ticket to contest in the local elections. Noor is from a conservative religious community where she cannot be open about her sexuality, and faces opposition for providing legal help to queer people. But she perseveres too, and continues to wage her legal battles for the rights of the LGBTQ community. While we don’t see either Mukhil, Alamelu or Noor directly engage with questions of faith, Noor often talks about the dichotomy between orthodox religion and queer identity and, at one point, says that one doesn’t need to fit into strict boxes to be loved and accepted by god. “There’s no one story of coming out, no one story of rejection/acceptance from family, no one story of dealing with religion in relation to identity. It was important for me to depict at least a glimpse of these complexities,” Nabi, the creator of the comic, once said in an interview, “…No one’s stories in Puu fit a cookie cutter type of characterisation; everyone breaks barriers, stereotypes, and common perceptions in some way, which is just how real life works.”

By incorporating both Hindu and Muslim myths, theological facts, and cultural history alongside depictions of healthy, abiding queer love, the larger message the comic tries to convey is that religion, faith and spirituality should not encourage exclusion, but rather, encourage love. And the governing emotion of the story is love: love that is all-consuming, love that is all-inspiring. Love that is a mingling of the spiritual, the sexual, the romantic.

Saboor and Jameel often talk about their love for each other in language reminiscent of the way devotees talk about the higher power they are devoted to, rife with spiritual references. Saboor and Jameel realise the depth of their love for each other after Saboor performs a devotional song, ‘Saansonki Maala Pe’ (On my breath, I weave a garland of your name) – which, as the author explains in their note, is “originally a bhajan sung by Hindu esoteric poet Meerabai and later famously rendered as a qawwali (South Asian Sufi devotional) by singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan”. It’s interesting, because Meerabai’s devotional bhajans written in praise of Lord Krishna have often invoked sensuous imagery and have had links with romantic love – and here too, Saboor mirrors that intense, sensuous, romantic love through his singing. “There is no sin on my beloved,” he sings, while the comic’s panel shows an image of Saboor and Jameel tenderly kissing each other.

In another episode of the comic, Saboor compares their love to the sufi concept of ‘fanaa’ – in which the person is a moth who is drawn to the flame, symbolic of the lover. As the author points out, ‘burning’ is a symbol for divine love in Sufism, and it is a leitmotif that runs throughout the comic, both Saboor and Jameel repeatedly talking about how their love for each other is so all-encompassing and intense that it feels like they’re on fire. In another scene, Jameel and Saboor are on a date, lounging beside each other on the beach, and they look up at the sky and see a half moon and stars. They call it ‘Chandra’ and ‘Rohini’ – who, in Hindu mythology were two deities (Chandra being the lunar deity) married to each other – and compare themselves to it, but also reflect on how the image of Chandra and Rohini together in the sky resembles an Islamic emblem. Again, their relationship reflects a secularism – a coming together of spiritual notions from various traditions, all of which symbolise love. And not just here, but all throughout Puu, there are similar examples of Saboor and Jameel being associated with sufi saints, devotional music, myths (from both Hinduism and Islam) conveying the notion of an omnipotent love that can triumph over any evil.

This idea is taken even further through another sufi motif that runs through the comic – the merging of the selves of the two lovers into one entity; wherein they love each other so much, they don’t know where one begins and the other ends. Jameel and Saboor often describe their love as being like this, of being two halves of a whole, of fusing together through the spiritual power of their love. But towards the end of this comic, this manifests in an escalated conclusion (and the art style too, becomes more surrealistic, the colours more vivid and jarring) where Saboor and Jameel both symbolically and physically fuse into one to defeat the homophobic forces of conservative religion. They have been burned way too many times by the world. They’ve been told by their maulana that their love is “unnatural” – which is particularly painful because the maulana has used the very language of faith that Saboor reveres so much, to denounce his relationship with Jameel. And so, Saboor and Jameel’s fused being takes the shape of a scorned deity, and focuses its ire on the homophobic maulana (who, here, is a stand-in for all the religious forces that seek to other and marginalise queer love) and this is the first time in the comic we see Saboor and Jameel, who are usually the embodiments of pure, divine love, express so much rage. Perhaps their rage is justified, because it is a product of the hatred and injustice they have both faced, but in the end, Noor does intervene, reminding them that it shouldn’t be rage that drives them, but love and compassion. “No matter how sacred you are, how lovely you are, you can never prove yourself to those who don’t care,” she tells them. “But there are those who will lift you up, help you grow, until you blossom into a garden.”

And it is an important intervention, because this is what reminds them that at the end of the day, they love each other and they have each other. Yes, the world is cruel, but the ‘beauty of god’ is not located in that cruelty, it is located within themselves. When their rage dissipates, even the maulana is inspired by the power of Saboor and Jameel’s love.

And so, Saboor and Jameel’s love continues to flourish, as does their relationship with their spiritual beliefs. Throughout the entire story, their unflinching, enduring queer love is a beacon of hope, symbolic of something transcendental and soul-reviving. In fact, when a character in the comic experiences an accident and is on the cusp of death, they dream about Saboor and Jameel – and in that dream, Saboor and Jameel give them the strength to carry on and keep fighting. And that is why Puu is so special, because it shows us that religion and faith can be reconciled with queerness (contrary to popular belief), and that spirituality can be located both beyond the self and within the self. Most of all, it shows us that sometimes, all you need is someone to hold your hand to blossom into a garden.

[1] Though Saboor identifies as genderfluid, the author uses he/him pronouns to refer to him throughout.

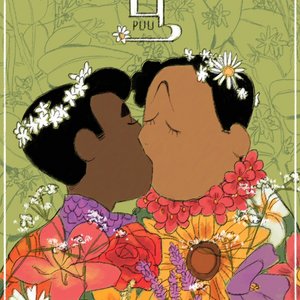

Cover Image: Puu Web Comic