‘A Girl Has No Name’

As a young student, I have learned about the double helix DNA model and its discovery being a tremendous leap for science. Deoxyribonucleic Acid – or DNA – forms the basis of life, and the scientists who discovered it, James Watson and Francis Crick, seemed to have found nothing short of the secret to life. What I had not studied, however, was the contribution of a third scientist, Rosalind Franklin, whose X-ray diffraction photographs had formed the final vital piece to the DNA puzzle. This vital piece of evidence was unethically provided to Watson and Crick by another colleague following which they won the Nobel Prize for the discovery. Rosalind Franklin succumbed to cancer and passed away a few years before the prize was awarded. She is scarcely acknowledged as having been part of the DNA discovery which remains popularly known as the ‘Watson-Crick Model’.

Wanting to learn more about this mysterious third scientist who contributed to the discovery, I chanced upon Brenda Maddox’s biography of Rosalind Franklin, aptly named The Dark Lady of DNA. Having been a chemistry student myself, I began devouring the book with great excitement, seeing familiar names and reading amusing anecdotes about the ordinary lives of some extraordinary scientists. The book is a series of incidents in the life of Rosalind Franklin, a woman scientist belonging to an aristocratic Jewish family, and is set within the backdrop of the Second World War and the holocaust.

Rosalind notes how as a child in school, the girls were taught science differently and how the science education received seemed “an intellectual endeavour calling for neatness, thoroughness and repetition rather than excitement and daring”. Her aunt very seriously describes her as “alarmingly clever” because she would “spend all of her time doing mathematics for pleasure and invariably get her sums right”! This ‘alarm’ at Franklin’s talent was mostly because fields such as Chemistry and Physics were hardly a woman’s domain and superior intellect in women was an embarrassment. Having been admitted into the science classes at Cambridge University, Rosalind recounts that women were given permission to attend lectures with men, but till about the 1930s were only allowed to sit in close groups near the front of the class. Apart from influencing university policies, sexist beliefs also permeated everyday conversations and the attitudes of male scientists towards their female counterparts. I was terribly amused at one point, when Rosalind is described as “pugnaciously assertive” by James Watson when she chooses to dismiss Watson and Crick’s initial DNA model on the grounds that it had faulty measurements. While Rosalind’s biographer highlights the struggles that women scientists experience in science, she also talks about aspects of Rosalind’s life other than her scientific career. Amongst other things, she makes references to Rosalind’s attraction to her co-worker, Jacques Mering, her hesitant discussion about sex with her close friend, and her highly meticulous care in choosing clothes.

This got me thinking more deeply about the intersections between Rosalind’s personal and professional life. I was clearly entering unfamiliar territory, trying to reflect on the issue of sexuality in connection to the lives of women scientists. Sexuality is closely related to gender power relations, and the trade-off to exist outside of these tightly gendered roles (whether within or outside of an organisation) seems to be a negotiation with one’s sexuality and gender identity. To me it seemed that to exist in a field that is largely male-dominated, women in science constantly had to ‘measure up’.

The Indian context

In India, during the early 20th century, women’s contribution to science faced much of the same challenges as they did in the West. In addition to this, science education was highly restricted. The pre-independence era saw a strong focus on Westernised science, and few institutions offered science education. Even in these, the medium of instruction was largely English, and this education was restricted to a certain privileged section of society. An Indian biochemist, Kamala Sohonie, was denied entry into the prestigious Indian Institute of Science during the 1930s by Nobel Prize winner C. V. Raman solely on the grounds that she was a woman and that she would be a distraction in the laboratory! Although Sohonie finally confronted Raman and ensured her entry into the institute, she notes that within classrooms, casual discussion and debate with male colleagues was largely forbidden, and women were socially isolated.

In this aspect not much has changed over the past few decades. Women scientists feel the need to be aggressive in order to be taken seriously and at the same time are considered unpleasant and unamiable because they are not feminine enough! In an India Today article, a neuroscientist at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) talks about the biases that women scientists face, and recalls,

A colleague quipped that I was in the difficult position of having well thought-out opinions, the guts to voice them, but no Y chromosome.

Today in terms of enrolment and sheer numbers, the story is slightly different. According to a report by The Association of Academies and Societies of Sciences in Asia (AASSA), women make up almost 40% of students in science at the undergraduate level and nearly 25-30% at the higher PhD levels in India. Sounds promising, but consider this: While an increasing number of women are opting to enter the field of science, very few end up securing top positions in research or administration. For instance, in premier research institutes such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Indian Institute of Technology, and Indian Institute of Science, women constitute a meagre 10-12% of the faculty. The report attributes this ‘glass ceiling’ that women encounter within the workplace to the social pressures of having a family and the burden of child care.

The AASSA report highlights that the proportion of women scientists who have never married is much higher than that of male scientists. Interestingly enough, almost 50% of married women scientists have married individuals within the field of science, which is not so in the reverse case. These data make me wonder whether women in science make a conscious choice to not marry/have children because it helps avoid the balancing act between their work and family, and child care roles. At the same time, in a culture that does not allow for women to make these decisions very easily, how much agency do women have to choose not to marry or to not have a child?

What is quite unique to the field of science is that the fast paced development of science and technology makes these choices all the more difficult. Recently, two journalists who have been travelling around the country interviewing women scientists about their work and their personal lives began a blog. In one of the interviews, Radhika Nair, a cancer biologist, talks about how for women scientists any time away from the laboratory can be crucial because it means losing out on new technologies. In a BBC article about women space scientists, Minal Sampath, an engineer working on India’s mission to Mars, says, “We were working up to 18-hour days sometimes…What the job takes away from me is that when my son is sick, when he needs me, I am in Bangalore repairing some system there.” Women scientists seem to be constantly walking a tightrope – between societal norms and roles on the one hand, and gendered discrimination within science on the other.

Women scientists are also largely unable to voice their opinions within the scientific community or make any significant impact on policy. The primary reason for this being that they lacksolid social networks within the scientific community. These networks are also crucial to obtaining grants for research, access to funding agencies and so on. In an article in The Ladies Finger, Shobhana Narasimhan, a theoretical physicist at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, expresses that even through something as simple as men catching up for drinks after work, informal networks and significant spaces are created to share valuable information. Women are largely excluded from these spaces.

It is important to consider these numerous cultural and organizational obstacles women scientists face even today. When I think back to Rosalind Franklin’s story set in the early 20th century, it underlines the realisation that the field of science continues to view women scientists as an anomaly. Without accounting for its women scientists, science, in my opinion, will remain archaic and deprived of all the Rosalind Franklins that are yet to be discovered.

—

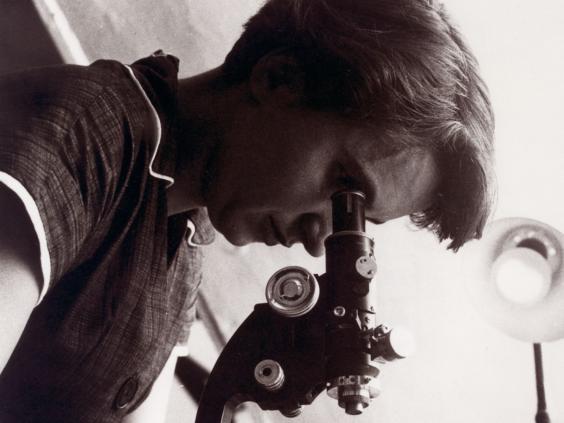

Cover mage: The real Rosalind Franklin (Universal History Archive/Getty)