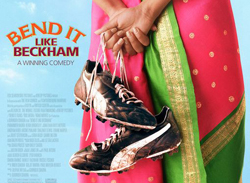

‘All I have to say is sporty spice is the only one without a bloke’ is the warning given by Kiera Knightley’s mother in Gurinder Chadda’s Bend it Like Beckham. The film was released in 2002, and launched the now famous career of Oscar winner Kiera Knightley and Jonathan Rhys Myers. Parminder Nagra plays the protagonist of the movie Jessminder (Jess) Bhamra. While Knightley and Rhys Meyers has gone onto become Hollywood celebrities, Parminder’s brilliant talent remains short-handed within (white) Hollywood world. Scholars of feminist and queer theory have written profusely about the film’s tackling of sensitive topics such as the participation of women in sports, the relationship between the characters of Jules (enacted by Knightley), Jess and their coach Joe (Rhys Meyers). In this brief rumination I wish to highlight the relationship portrayed between Jess, and her family, especially the mother-daughter relationship.

Shaheen Khan plays the indomitable migrant Punjabi mother, who cooks, prays, and polices both of her daughters’ gender presentations. Her older daughter is about to marry a man from within the Sikh community, whereas Parminder is focused upon a career in football and falls in love with an Irish football coach. The movie journeys through Jess’s struggle to break free from the chains of her traditional Sikh family. She finds support and friendship with Jules (Juliet) who is also haunted by her mother. The two girls play football across Europe, and are finally able to receive scholarship at an US university. The spirit of David Beckham haunts the viewers throughout the movie. He makes a cameo appearance in final scene with Victoria (Posh) Beckham. While Jess and Jules are getting ready to board their plane to the US, the famous British footballer and his pop star wife walk through the airport. Jess’s mother remains a difficult figure to grapple with throughout the film. What do we make of her gender policing? How do we make sense of the complex ways racism, sexism, and being an immigrant in the UK frame her fears for both of her daughters? And, most of all what does this intimate mother-daughter (troubling) bond represent for many young girls who are seeking a career in sports and athletics? Are all mother-daughter relationships doomed with haunting narratives of gender policing? And, most of all why is the Punjabi mother a comical character in the film? In all the ways we want to save Jess from traditional patriarchal roles, we seem to laugh at her mother with utter disdain for her ‘backward’ ideas. The traditional yoke of sexism is intricately woven in the text of a somewhat progressive film as we laugh at her mother, and even at Jess’s older sister who is seeking the ‘perfect Indian wedding’.

I raise these important questions as a queer migrant viewer of the film across two nations. In the US, the film was released shortly after its UK release. I sat through an auditorium filled with white Americans laughing at the comical representations of Jess’s mother. I shuddered, wondering if I could join or not, how would the white people interpret me laughing at another Indian woman? Was I being a sexist Indian male viewer? Most importantly how does racism and sexism frame the immigrant Indian woman while still imagining a potential future for the UK born Indian woman? In their article titled ‘The Remaking of a Model Minority PERVERSE PROJECTILES UNDER THE SPECTER OF (COUNTER) TERRORISM’ Jasbir Puar and Amit Rai warn us of the ways the film represents a history of progressive diasporic films as well as the comodified ‘Planet Bollywood’ phenomenon (Puar and Rai, 2004). Truly, the film makes a commodity of many young girls’ aspirations to join sports. The commodification is predicated by caricaturing the immigrant mother. No doubt, girls and women face everyday barriers towards participating in athletics. Women’s sports receive unequal public and private funding, and undoubtedly, mothers police their daughters’ gender roles. Sadly, what goes unexplored is the tremendous pain of an immigrant mother who has to balance between the racist UK landscape and patriarchal gaze of the immigrant family. So we laugh at our mothers, only to allow our daughters to be saved by liberally minded white (wo)men. While the movie ends with Jess and Jules leaving for the utopic US, in reality Parminer Nagra could only be featured in prime-time television ‘ER,’ while Knightley and Rhys are celebrated Hollywood Stars. In conclusion, I seek to incite our readers not to blindly accept the liberatory version of feminism embedded in the film, but to view it within the context of racism, global inequality, and gendered power relations. Injustice will also be done to Gurinder Chadda (film-maker) if we view her career through her (only) mainstream success. We must critique, question, as well as enjoy while bending it like Beckham.