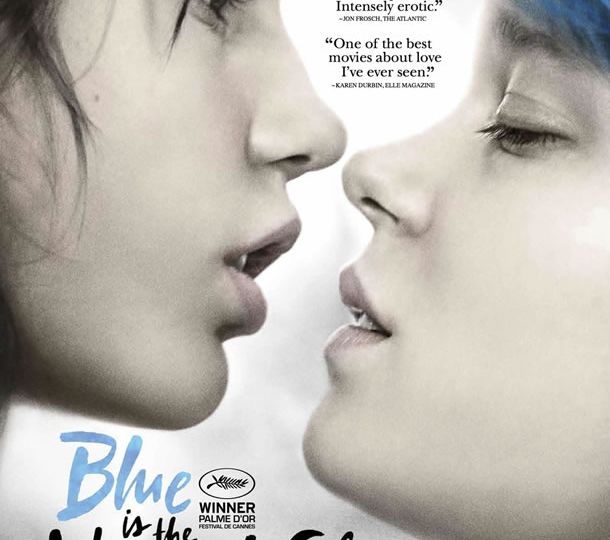

There are many ways of looking at Blue is the Warmest Colour, last year’s French release about a love story between two young women that went on to win the highest award at the Cannes Film Festival. We could look at it as a love story, a timely twist on the classic Ali MacGraw-Ryan O’Neal genre-defining Love Story or the more contemporary When Harry Met Sally. We could look at it as a same-sex love story, girl meets girl, rather than a straight love story, boy meets girl, which then begs the question: Is queer love any different from straight love?

Or we could look at it as a film that celebrates the act of looking, the sheet sumptuous pleasure of looking, or scopophilia as Freud would have called it.

Based on Julie Maroh’s 2010 graphic novel of the same name, Blue is the Warmest Colourrevolves around Adele, a 15-year-old high-school student in the French town of Lille. Like many of her contemporaries, Adele is in the mood for love. After a brief dalliance with a young man and an unexpected liplock with a girl in her class, neither of which bloom into anything, Adele encounters a young woman with blue hair on the street one day. As this blue-haired woman starts to occupy her daily thoughts, Adele allows herself to be taken to a lesbian bar for the first time and meets Emma, the subject of her fantasies. A budding friendship flowers into a passionate sexual encounter between the two, slowly settling into the ups and downs of a relationship in the making and the breaking – all over the course of 179 long minutes.

Looked at through the linear lens of plot, Blue is the Warmest Colour doesn’t need three hours to tell its tale, which is no different from any other in its genre, regardless of the gender or sexual orientation of its protagonists. Girl meets girl, girl leaves girl. That’s all there is to the plot. But as the film languidly progresses from one scene to the next, our pleasure – as viewers – comes not from tracing the narrative arc, but from lingering on the small details of the unfolding relationship. From looking at these, with the unhurried pace and the unbroken intensity of complete absorption.

And there is so much to look at in Tunisian-French director Abdellatif Kechiche’s leisurely masterpiece, so much of what influential feminist film theorist, Laura Mulvey disparaged as ‘visual pleasure in narrative cinema’ in her iconic essay. First and foremost, Adele. Much has been written about the exceptional performance of 19-year-old actress, Adele Exarchopoulos, who played this eponymous role. But it is hard to describe the holding power of an arresting face in an art form that is, at its heart, visual. Only once before can I remember seeing a film that gave so much power to a woman’s face: that of Renee Falconetti playing Joan of Arc in continuous close-up in Carl Dreyer’s 1928 classic.

Then there’s the sex. Outside of pornography, sex between two women is rarely seen in the movies. And rarely does it come so graphic, so real, so sexy, as it does here. Or take up so much screen time. Or seem so integral to the tale. Watching the 20+ minute sex scene between Adele and Emma that signals a turning point in their relationship, I was reminded of feminist bell hooks’ comment in an entirely different context: ‘We are watching a normally unauthorized picture, an unauthorized body…unauthorized by society, religion, morality.’

Not surprisingly, the extended sex scenes were not that easy to shoot – and were somewhat controversial. In an online interview, Seydoux, who plays Emma, said that the longest sex scene took 10 days to film, that fake genitals were used and that the shoot made her feel like a ‘prostitute’.[1] Maroh, who wrote the novel on which the film was based, has since said that the film degenerated into ‘a brutal and surgical display of so-called lesbian sex, which turned into porn’. I’m no expert, but as a viewer I found the portrayal of sex between the two women compelling and convincing. And far from gratuitous. By not leaving out the sex, the film allows Adele and Emma to emerge as sexual subjects in their own right, a screen status that is rarely accorded to women. It also doesn’t inadvertently typecast a female relationship as chaste, sexless, or lacking sexual desire.

Perhaps Blue’s biggest contribution to cinema in the long run will not that be it includes lesbian sex, but that it reconfigures, subverts, or even breaks, the notion of the ‘male gaze’. Ever since Laura Mulvey theorised in the 1970s that women on screen (coded with’ to-be-looked-at-ness’) are the objects of the male gaze (constituted through camera positions and male viewers, who are the ‘bearers of the look’), we have been stuck at much the same spot, consistently assuming that films – specially those that portray sex explicitly – are made only to give visual pleasure to the world of men. Mulvey wanted to stamp out the visual pleasure of gazing on beauty – by analysing it. Ironically enough, Kechiche gives us back the visual pleasure of narrative cinema, the joy of looking at beauty, by creating a film for all our gazes.

This post was originally published under this month, it is being republished for the anniversary issue.