“Today I ask if I’ve found a place among the rest, who studied, read, wrote and passed the test in cap and gown. Today I hope you see a man upon this stage.”

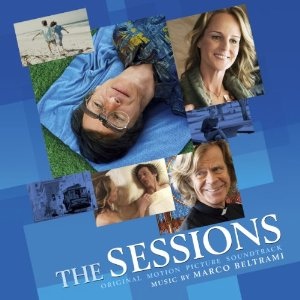

In his opening monologue in the film ‘The Sessions’ (2012), Mark O’Brien encapsulates in a single sentence his anxieties, insecurities and latent desires of ‘hoping’ to live as someone not defined by his disability. Inspired by his path breaking 1990 essay titled ‘On Seeing a Sex Surrogate’, the movie, ‘The Sessions’ follows O’Brien, a poet and a graduate from Berkeley who is living his life within an iron lung due to complications from polio. The heart of the movie lies in O’Brien’s relationship with Cheryl, the sex surrogate he hires for six sessions, which the movie transforms into a profound and joyous exploration of sexual desire that makes the disability just an innocuous facet of O’Brien’s much more candid, multifaceted personality.

Our movies have usually had a dull, staid way of highlighting disability. They usually begin with focusing on creating an immense empathy for the protagonist followed by the said protagonist’s awe-inspiring ‘resistance’ to structures that intend to keep them chained to their disability, and finally conclude with a rousing sentiment of appreciation and gratitude to the protagonist for having paved the way for many others by their sheer courage and conviction. Such approaches not only make the disabled person an object that invites pity and sympathy but alternately try to convert them into a poster child for heroism.

The Sessions keeps it simple. Two adult individuals, one of whom happens to be disabled, engage in a mutually satisfying sexual relationship that is not limited by any grand ideas of love or romance. Thrown in are O’Brien’s intense albeit hilarious conversations with the Catholic priest, Father Brendan. ‘My penis talks to me, Father Brendan’ says O’Brien and on being informed of the latter’s decision to see a sex surrogate, the priest remarks ‘I have a feeling that God is going to give you a free pass on this one. Go for it.’ While reams have been written and volumes have been spoken about religion’s oppression of sexuality and sexual desire and deeming as blasphemous any expression of sexual pleasure, ‘The Sessions’ is unique in its humane treatment of the relationship between a believer and his priest and the tacit understanding that religion and faith may not always be the best answers to life’s more complex realities.

O’Brien, through the lens of this movie, becomes an active sexual being, who craves human contact and pleasure and intimacy. The sex is aesthetic and moving and sensual and erotic and challenges the predominant, pervasive ideas of ‘acceptable’ normative sex being one which is necessarily ‘able-bodied’ and thereby ‘more’ beautiful and (usually) heterosexual. To most, the movie will be a fresh perspective on the relationship between disability and sexuality, subverting the dangerous ideas of both ‘passivity’ and ‘resistance’ that tend to be usually ascribed to people with disabilities but to me, the movie is no grand socio-political statement but is, simply, about the universality of desire and human intimacy and that all bodies have the potential to be or want to be ‘sexed’ bodies. I am reminded of one of my favourite parts of the movie where Cheryl points out to Mark after one of their sexual encounters “You’re a fully fledged male homo sapien endowed with a handsome and substantial penis which now has a proven track record.”

I was struck by how the film addressed the fluidity of sexuality and sexual intercourse. Avoiding any and every stereotype that shape our understanding of that effervescent idea ‘love’, the movie makes sexual desire a humane, possible, accessible to all and alternately an awe inspiring yet possibly ephemeral idea, that does not have to be limited by societal dicta. The spontaneity, humour and warmth of the relationship between Mark and Cheryl challenges and subverts our, often, restricting ideas about love and relationships.