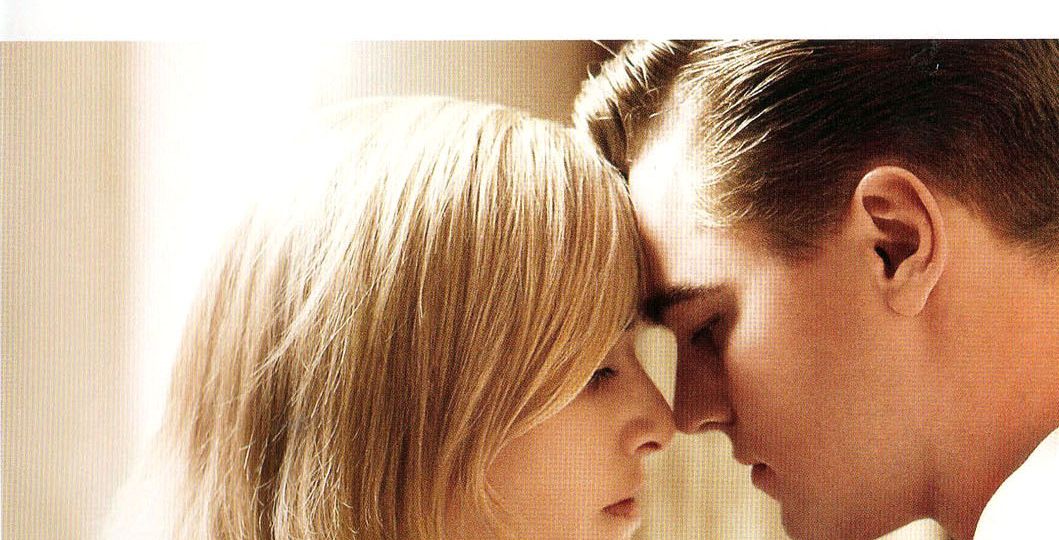

To their neighbours, as to themselves, Frank and April Wheeler are ‘special’. Not for them the middle class aspirations of conformity and prosperity. Inspite of her failed acting career and the fact that most of her days are spent in looking after her children and her home, April refuses to resign herself to the role of suburban housewife. There is greater authenticity in her defiance of a life that has not lived up to its promise than in Frank’s ironic acceptance of his role of a city office worker, spending his days at a job he hates, as fulfillment of his responsibility as the ‘breadwinner.’ While they continue to be perceived with admiration from a distance by their more conventional neighbours, they are not so different from them in the life they have adopted, though it takes them time to admit it.

In a desperate bid to find meaning in their lives, April persuades Frank to relocate the family to Paris. They believe that Paris would be the place where Frank could find his true calling, away from the suffocating conformity of their present mode of living. April would support him by taking up a secretarial job in a government agency, thereby freeing him from the constraints of his gendered responsibility of being the breadwinner. There is no consideration of the double burden that would fall to April’s lot in earning to support the family while discharging her primary duty of care-giving. Nor is there any discussion of what was to be April’s true calling and how and when she was to discover it. We are led to assume that it is sufficient for her to break the conventional norm by migrating along with her family to take up a job in a foreign land, thereby buying her husband time to indulge in a journey of self-discovery.

The proposed plan of migration stabilizes their relationship and causes Frank to end a casual affair he has started at the workplace. Their neighbours as well as Frank’s colleagues at office find it difficult to comprehend what inadequacy in their current situation could force the Wheelers to take such a drastic step. The only one who comes close to understanding is the son of one of their neighbours – John Givings – a mathematician who has recently returned from an institution for mental illness. It is perhaps his marginalized position in society as a ‘certified lunatic’ which allows him to see what the Wheelers mean by the ‘emptiness and hopelessness’ of their current situation.

Their plans for Paris are suddenly thrown into question when April discovers she is ten weeks pregnant. Meanwhile, Frank has received an offer at work for a promotion and better pay. He doesn’t accept the offer outright till learning of April’s pregnancy which gives him a ready-made excuse to abandon the Paris plan. April confides in him that she would like to undergo an abortion within twelve weeks but it is clear that he is not altogether in support of her decision.

Though, in planning for Paris, Frank had no qualms in agreeing to subvert the traditional masculine gender role in living off his wife’s earnings, it soon becomes clear that it is not to be at the cost of his wife’s relinquishing her primary role as mother and care-giver. When the Givingses and their son come over for dinner, Frank announces that they are not going to Paris anymore because April is pregnant. When John Givings confronts him with the truth that he is merely making an excuse of his wife’s pregnancy to cancel their plan, he turns violently angry causing his guests to leave. Later in a violent row with his wife, he tells her they cannot have another child on a narrower income than usual in Paris and so he is planning to accept the offer of promotion.

At this juncture we learn that it was an unplanned pregnancy which first caused the Wheelers to settle down and move to Revolutionary Road and Frank to take the job so he could support the growing family. A second child followed soon and the Wheelers’ resignation from life as they knew it was complete. Though April has insisted throughout that the plan to migrate was to help Frank explore his interests so that could define himself by his choices, for him, April’s life choices must continue to be dictated by her biology. It doesn’t matter that they already have two children and may not be able to afford having another. It doesn’t matter that his wife may not want another child. When a distraught April asks him if he himself wants another child, he accuses her of her ‘unnatural’ behaviour for a woman and a mother and declares himself completely opposed to an abortion. He even accuses her of insanity which he conveniently defines as an inability to relate to or love another person.

The next morning, April takes on an unnervingly calm and pleasant demeanour as she cooks breakfast and talks with her husband about his work – the perfect caricature of the sane, feminine, happy suburban housewife. In the non-diegetic (meaning, things which occur outside the story-world) world of their time, the second wave feminist movement was soon to burst this very myth of women’s contentment in the gendered division of labour and their acceptance of their biological role of mothering as destiny. When Frank leaves for office and the children are away at their neighbours’, April attempts to perform a manual vacuum aspiration abortion on herself, though it is past the twelve week period of gestation that she considers safe for the procedure. She has no other way out of the situation, or perhaps it is her attempt at reclaiming control over her own life. Sadly, the procedure fails at the cost of her life.

Towards the end of the film, we find that a widower Frank has moved to the city, taken up the new job offer and is devoted to his children. Meanwhile, on Revolutionary Road, the Givingses have discovered in another young couple the qualities of compliance and congeniality, so becoming of the suburban neighbourhood, which the once-special Wheelers were proved to have lacked.

It is interesting that though the progression of the story imputes all the bitterness and dissatisfaction of the Wheelers’ lives to the fact that they have children, the children themselves occupy very little screen time. The children, though loved, are the choice they never made. This film highlights the importance of choice in shaping one’s sense of self and therefore one’s life. It also brings to the fore the contradictions inherent in notions of what constitutes ‘normal’ as well as the constraining nature of gender roles which deny this choice at the cost of women’s rights and the dehumanization of both men and women that must necessarily follow. Frank’s story depicts the nature of patriarchal expectations of masculinity at the cost of suppression of personal growth. It is April’s story however which shows the violence of patriarchal control over women’s bodies in the infringement of their right to bodily integrity and well-being. This control which seeks to align all bodies and identities to the model of reproductive heteronormativity extends not only to women but also to all people whether or not they conform to this norm.