In the early 19th century, a woman known as the Hottentot Venus was displayed in England and France as an object of curiosity. A black woman from the Khoikhoi tribe of South Africa, she had voluptuous breasts, buttocks and labia that drew large crowds at the many freak shows where she was an exhibit. Now known as Sara Baartman, she was sold into slavery around the age of 20 years, and died before she turned 40 from ill health caused by overwork and abject poverty. Until recently, her dissected and carefully preserved body was displayed at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris for its unusual anatomy. In the mid-1990s, debates on Western representations of black female sexuality led to an eight-year political row between France and South Africa, before her body was returned to her people.

Sara Baartman is perhaps one of the most famous human exhibits of Freak Shows that evolved as popular forms of entertainment for the growing metropolises in imperialist Europe, England, and the Americas between the 17th and 20th century. Freaks were people with exaggerated secondary sexual characteristics, uncommon anatomies, ‘deformities’ and disabilities displayed to the public in these shows as ‘odd human exhibits’. Popular shows boasted of bearded women, women with large breasts, giants, midgets, conjoint twins, people from colonies in South America, Asia and Africa, and people with multiple ‘deformities’.

No two human bodies are alike, and our different bodies arouse curiosity. But our fascination for the aesthetics of the perfect human body has historically created a space within art, science and religion for the examination of the ‘abnormal’ and the ‘imperfect’. As a result, some bodies are normalised while others become oddities. Freak Shows, and to a large extent, circuses and even exhibits in medical or anthropological museums particularly stand out for dehumanising and objectifying these different anatomies, and oftentimes subjecting these bodies to violence and discrimination. Some historic accounts talk of people who exhibited their bodies out of their own will, and in unabashedly displaying features of which they were taught to be ashamed, they found empowerment and pride. But freak shows were also grounds for exploitation because of the association of ‘abnormality’ with ‘evil’ and the gross insensitivity towards cultural, sexual and racial differences between human bodies.

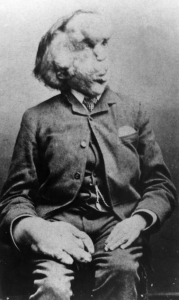

Some of the oddities were medical conditions then unidentified, and several ‘freaks’ became object of scientific curiosity. Famously, there was Joseph Merrick, who was posthumously diagnosed with two illnesses: neurofibromatosis and Proteus syndrome, both of which caused severe deformities, leading to his show name the ‘Elephant Man’. Although Merrick was a white man and a citizen of England, he was exploited much like Sara Baartman; during his lifetime and after his death his body became an object of interest for the general populace and the medical community.

In the post-colonial era, Freak Shows have themselves turned into ‘objects of curiosity,’ for scholars, writers and filmmakers, who have reversed the gaze to study the people who enjoyed this form of entertainment. In an essay on the Hottentot Venus, Sadiah Qureshi points out that the practice of collecting and displaying humans from the colonies was no different for the Imperialists than displaying native flora and fauna. While the forms of entertainment in England and France varied from theaters, operas, zoos and public gardens to circuses, freak shows and fairs, she points out that all of these were essentially collectibles on display.

Books and movies have also examined the impact this gaze might have had on the ‘human objects.’ Gaston Leroux explores this theme in his masterpiece, the Phantom Of The Opera, where Erik, a disfigured boy disowned by his parents and cruelly tortured at a French freak show, recedes into the catacombs of the Paris opera house, coming out only to gaze at a beautiful female singer whose voice entices the very people that rejected him. When she rejects his love, he channels his anger into creating an underground chamber where he hopes to hold her captive as his own prized possession.

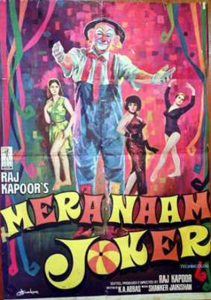

Indian cinema explores acceptance and rejection of ‘oddness’ through films on circuses, which offer a unique entertainment in the form of the circus clown, whose unfortunate predicament becomes comic relief only because of his odd appearance. Very often the clown is a midget. In the 1972 film, Mera Naam Joker (I am called the Joker), Raj Kapoor challenges the notion of ‘entertainment’ as he traces the struggles and losses of a man who wants to make other people laugh. In the 1989 Tamil Movie, Apoorava Sagotharargal (Wonder Brothers), Kamal Hassan plays twins of whom, the older one, born a dwarf, works in a circus and finds acceptance and power within his circle of friends only to be rejected later by his paramour because of his abnormal height.

Carnivale, an HBO drama (2003- 2005) that tells the story of a travelling Freak Show driving through the Southern American states in the 1930s finds unique ways of subverting the gaze. During show time, Carnivale, follows in the cruel tradition of its historic counterparts and deliberately objectifies the ‘odd human bodies’. There is Lila, the bearded woman; Alexandra and Caledonia, conjoint twins whose loosely tied skirt displays their joint hip; Rita Sue, the nude dancer with huge breasts; Lodz the blind mentalist; Gecko, the lizard man with a deforming skin disease; Ruth, the snake charmer; Samson, the midget; Apollonia, the catatonic fortune teller and several others. But then the camera reverses the gaze and peers as curiously at the village folk who watch these different bodies with such shock and revulsion that it instantly turns them into ‘freaks’ for the modern viewer.

Carnivale triumphs on another front as well. In spite of the ‘deformities’ and painful disfigurations, the members of the travelling freak show display their bodies out of their own free will, and, through their common pride, find a home and a family with each other. They also find complete acceptance, love and sexual satisfaction. In a scene where Lila the bearded woman shares a sensuous kiss with Lodz the mentalist, he seems to admire the growth on her chin rather than seem inured to it. Its shortcoming is its all-White cast, and its failure to challenge racial exploitation within travelling freak shows.

The characters of the Carnivale are in a sense comparable to the subjects of Diane Arbus photographic work on ‘freaks.’ Arbus exhibited pictures of people who were pariahs from society, because they did not conform to the 70s’ definition of ‘beauty’ or ‘normal’, or were isolated for features that caused revulsion and shock. Arbus takes a very different path from that of the freak shows: she does not seek to display their ‘oddity’ or capture their isolation; she only tries to acknowledge their existence. As Susan Sontag, writes in her essay America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly, Arbus’ work shows that ‘humanity is not one,’ and that human bodies come in all shapes and sizes. Through her unbiased and non-objectifying gaze, she acknowledges difference rather than oddity, allowing her subjects to feel empowered and in control of their bodies.

Freak Shows still continue to exist. There are people like the American entertainers, The Enigma, The Scorpion and Marcus ‘The Creature’ who voluntarily display their congenital deformities, or have modified their bodies through tattoos, piercing and even surgery in order to be part of such shows. The audience hasn’t disappeared either. Videos about people like ‘The Human Barbie’ still go viral around the globe. And if you look for the world’s 10 weirdest people on Google, you will find You-Tube videos and photographs of ‘odd’ bodies painstakingly put together. Many modern day freak shows continue in the tradition of the old by objectifying human bodies, and inviting people to gaze in a manner that deepens the fissures between ‘normal, and ‘abnormal.’

Over time, freak shows have also morphed. Cinema around the globe borrows from the tradition of the theater and the circus by introducing the ‘comedian,’ who not unlike the clown or the jester is the ‘odd’ counterpart to the ‘hero.’ His ‘oddity’ makes the protagonist seem more ‘normal,’ and unless carefully played, the ‘oddness’ exaggerates racial, sexist and cultural stereotypes.

And once again that is where Carnivale scores. In the very first episode, the ‘normal’ protagonist Ben, who earns his wages by pitching tents, runs into Gecko, the lizard man, for the first time. Gecko, suffers from a medical condition that causes his skin to form thick, diamond-shaped, discolored plaques all over his body. Additionally, he has a stubby tail. When Ben seems partly surprised and partly repulsed, Gecko asks him, ‘What are you? Some kind of freak?’ Looking around him Ben sees the differently shaped bodies that place his own in a peculiar space: he isn’t ‘normal’ anymore; only as different as any of the others. And right then, he learns to see differently, as do the viewers.

—