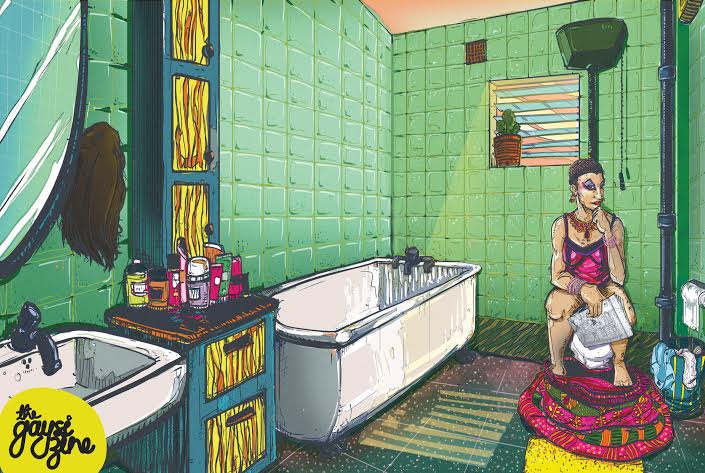

The Gaysi Zine is brought out by Gaysi Family, a blog to provide a voice and a safe space for queer desis. The Zine started in 2011; it’s been brought out every year since then, but this is the first time it has come out in the form of a graphic novel. It’s visually intense and abundant. Colours, illustrations, words overflow madly, as though there’s not enough space in the world to say it all. I approach the Zine incredibly excited; comics have been so well-loved by the queer community (Dykes to Watch Out For! Blue is the Warmest Colour!) and also by desis (Tinkle! Champak! Amar Chitra Katha!). Visual culture is important to us. Gaysi Zine’s fourth edition makes you wonder – how did no one think of this before?!

The February issue of In Plainspeak is all about love. So let’s start with Love in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: seven pages of people having fun at a very queer club.The title alludes to the influential essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin, in which he analysed contemporary art througha Marxist lens, and said that reproduced art loses something; it is differentiated from the original piece by virtue of losing its context and authenticity.

What does “mechanical reproduction” mean for love and sexuality and queerness? For gaysis?

It sounds boring!

It sounds repetitive – sex and love that is mechanical; a cultural script enacted again and again and again for the purpose of biological reproduction. It’s already been done. Queerness, the writer seems to say, is in opposition to that. This comic is irrepressibly fun. Tongue in cheek, it plays with these ideas through phrases in digital fonts, arranged to look like newspaper clippings, arranged to look like a ransom note, all arranged on top of hand-drawn art. Whew! The layers. These are fonts and styles that have already been created and seen, but are unpredictably collaged – “There [are] no fast rules,” as a piece of text says in this story.

People – supporters of the cause – often find it easy to support queer rights by imagining queer relationships and love are exactly the “same” as they have always been taught love is, was, will be, and should be. The same love. Always the same; always comprehensible. Love is this essentialised inflexible thing – and of course, it should, was, is, and will forever be, fulfilled by romance between two people, of the same age, with an intent towards dating, marriage, having babies (and sex is somewhere in the periphery of this whole arrangement).

Of course, queer love can be like this. But I think it also goes beyond that – and for queer people, love holds a lot of different connotations than it does for others. The Zine embraces these nuances; in it, love is never what we expect or want it to be. The very absence of that narrative keeps reminding us of that expectation, making us feel slightly embarrassed for even expecting or wanting it. It’s true: a lot of queer people are the biggest closet (ha) romantics you’ll ever meet, despite how glamorous and cool we might seem.

The very first story in the anthology is called Going the Solo Route: Notes from a Travel Journal. It’s about a woman who likes travelling and living alone. What? That’s not the narrative we would expect to see as the introductory piece. Where is the love story? Is she even queer? It seems like it has almost been accidentally placed there. But somehow, I loved it; it pointed to the ethical, feminist choices queer women make in how we live our lives. We refuse to be defined by our relationships and partners. Solo Route is about loving and valuing ourselves – and self-love is quite often pretty damn queer in this patriarchal, heteronormative society.

But the Zine doesn’t stop at this uncomplicated narrative; indeed, that is just the start of exploring the question of how queer desis love. The amalgam of love-desire-romance keeps showing up in really difficult ways in the book. It’s never cute. It’s dysfunctional, and kind of fucked up. Café Mondegar alludes to the history (and present reality) of gay men who cruise for sex – for fun, for pleasure, for temporary freedom from the closet. It also enacts that uncomfortable stereotype of predatory gay guy “converting” a straight (?) guy, of wheedling him into sex, (“He just needed to be cajoled into it. Like a baby.”) despite discomfort and something that doesn’t quite look like consent. Let’s Dance confronts another uncomfortable stereotype that has occasionally seriously divided queer women – the “bi-curious” straight woman playing with the feelings of “actually queer” women. We are reminded that, yeah – this is how it goes, sometimes. Queer people don’t enter relationships as individuals; we carry all the baggage of the closet and heteronormative stereotypes with us. Why do we push back against these stereotypes so much? Why do we feel uncomfortable? Or maybe we don’t. Let’s talk about it.

And then sometimes love is really, really sad. Some of the most powerful stories in the Zine are about death: for example, Laxmi/Dearest Latha, and A Familiar Stranger. And that is the most affecting way in which we are reminded that love-relationships-desire-romance-longing-belonging is totally awful sometimes – especially for queer desis. We often have much to grieve about, existing in our contested spaces. In A Familiar Stranger, a woman deals with the loss of her child. We are not told anything about the family except that the child died while studying abroad; yet somehow – in fact, perhaps because of the lack of closure – we intuitively know this story. It is our story. We lose parents, family, friends, chosen family, and full citizenship, in the mundane course of living our lives. Many of us take our own lives. Many of us get sick. In Laxmi/Dearest Latha, a friend/lover/chosen family member is lost. The narrator enters a new phase of her life in the wake of this loss, grieving, but moving forward. What else is there to do?

The stories in the Zine are interspersed with posters created by Gaysi over the years for certain Gaysi events or campaigns. Silence Speaks points out the silence of political parties in the wake of the Supreme Court’s IPC 377 judgment. Another poster designed around the same time is called Aag Lagi Tan Man Mein. It is done in the style of a retro Bollywood poster, and cheekily celebrates “Same Sex Pyaar – Part of Bharatiya Sanskaar.” The Zine concludes with A Timeline of Events in LGBT History, written and illustrated by Maitri Dore. As such, it becomes an archive of contemporary queer history in India, and points to the various ways in which this community has come together, and been there for each other.

History is therefore important in this anthology, and there is also an emphasis on opening up narratives of queerness in sub-continental mythologies. There is one ethereal piece IlaSudyumna, which is about a king who becomes a woman because of a spell and finds that they quite like it. There is also Kamakhya Temple, evocatively illustrated and written by Amruta Patil, which narrates a trip the author took to visit the temple of Kamakhya, a goddess who is “all desires embodied.”

The Gaysi Zine, Issue 04, is spectacular, novel, and moving. It is a thrillingly creative and fun addition to the world of queer Indian literature. The most important thing that I think it does is that it creatively embraces and uses unusual forms of artistic expression – forms that are often marginalised, like posters, comics, and of course, the zine. It would be fascinating to explore how the queer community can use these forms in the future for productive activism through art. However, the Zine does show weaknesses at times; and its greatest limitation is that while the narrative and illustrative styles are diverse and unusual, there needs to be more diversity in whose stories are told. The Zine almost presents a homogenized ‘queer desi’ lived experience, an experience that’s isolated and disconnected from other forms of oppression. That is simply not accurate, and reflects a worrying tendency present in queer movements across the world: the tendency to present queer life in a very upper-class, majoritarian manner.There is a refusal to make the reader observe and understand lives influenced not only by heteronormativity and patriarchy, but also by caste, religion, and class. The success of The Gaysi Zine is a chance for us to reflect on limitations of queer activism in the subcontinent, and formulate strategies for intersectional activism. It is also a call for the people at Gaysi to use their visibility in this community to actively seek out and foreground intersectional narratives.

Images: Gaysi