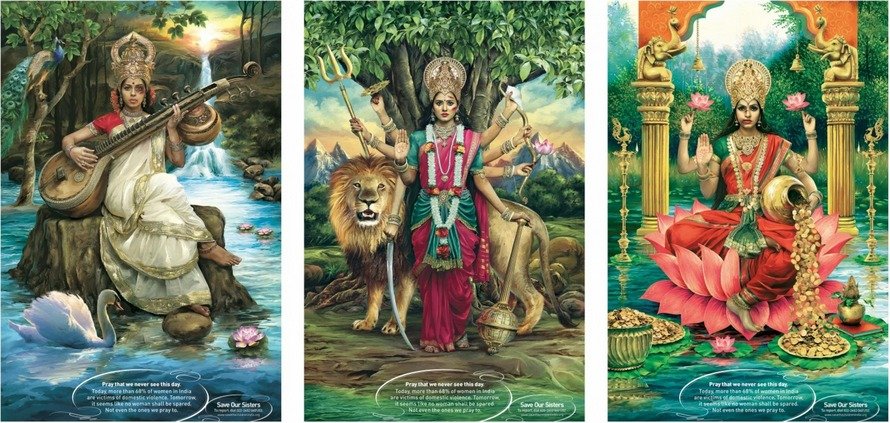

It is almost a year old, but the Abused Goddesses campaign created ripples in the fabric of activism that are worth revisiting. You’ve probably seen them too many times now, but I remember looking at the images for the first time and thinking how dramatic they were. Here were mythological characters from my grandmother’s stories, but in the avatar of battered wives. Saraswati had a black eye; Lakshmi had bruised swollen lips and Durga had an ugly gash running across her cheek. How grand the art was, and yet how disturbing!

At first glance, the art created by Taproot Images for Save Our Sisters, an organisation working on sex trafficking seem to challenge the often-reiterated contradiction between the worship and abuse of women in India. They seem to cleverly hold a mirror to the Indian people, asking them to see the brutalised faces of their religious hypocrisy. But as you take a long look at the images, several problems begin to emerge.

The campaign drew strong criticism from several feminists after Buzzfeed discovered it last September. Some of the most articulate pieces came from Brinda Bose who commented on the choice of the most domesticated goddesses among the pantheon of women in Hindu mythology, Nisha Susan criticized the deification of women and the failure of the campaign to address the nuances of domestic violence, and Sayantani Dasgupta who wrote about orientalism and the glamorization of domestic abuse. Yet the campaign took social media by storm. No one was sure where it had been published or released, or if it had been produced specifically for an awards-night. Nevertheless, the familiar faces, now bruised, caused everyone to stop, stare and be awed at the message they seemed to convey.

But what exactly was that message? An accompanying note read, ‘Pray that we never see this day. Today, more than 68 percent of women in India are victims of domestic violence. Tomorrow, it seems like no woman shall be spared. Not even the ones we pray to.’ Between the mute women who seem to be settling into the abused-wife role and the garrulous message, what exactly was the campaign trying to say: Men, stop beating women, because the next woman you hurt could be a goddess? Women, pray hard, because the new reality spares not even the goddesses? People, do you see where this country is headed? Today it’s the moral realm, but tomorrow it could affect the celestial realm?

The elaborate artwork works a little better without the accompanying message. It is a plush imitation of traditional goddess images that hang in Hindu homes. Now imagine waking up one morning to find these goddesses waiting for you with bruises on their faces. The campaign is hoping to capitalise on the resulting shock, and perhaps even the resulting shame.

But should we be shocked? We did not only just now discover that women are abused within cultures where the ‘feminine’ is revered. It might be shocking if we view them as contradictory cultural values with separate origins. But very often abuse works with deification, to create ‘good, ideal’ women who can be revered and others who deserve the abuse. Brinda Bose writes in her review of the campaign, published in Open Magazine:

‘…we know statistically that domestic violence is rampant in higher educated wealthy homes. So if we send men – any men, all men – the signal that we should worship women as (docile, happy Hindu) goddesses, and/or that since we (should, or profess to) worship women as goddesses, we should not hit them or kick them, we are telling them to consign and condemn their women to safe oblivion. And we are also telling them that any time their women fall short of their assigned roles as domestic goddesses, they can be abused for that original sin.’

But women do not have to fall off the pedestal to be abused. As Bose writes the ‘safe oblivion’ is a form of condemnation. The campaign shocks us, only because we encounter a visible form of violence we haven’t seen before in Hindu folklore. But domestic violence is more than physical violence. It includes emotional, economic and sexual abuse. Woven into folklore are stories that though narrated through the lens of the goddess reflect the real experiences of real women. Some of them betray other forms of spousal abuse we are asked not to question. There is Parvathi, who had to create a boy to guard her doors from Shiva, who would not understand her need for privacy. There is Sita, who had to walk through fire to prove her loyalty to Rama. These stories are valuable memories preserved by time, but they have also been used to normalise and rationalise subtle forms of oppression, domestication and abuse.

It is interesting that the campaign chose Saraswati, Lakshmi and Durga, three goddesses who emerge as central deities only because mainstream patriarchal Hinduism focuses on the might of their divine spouses. There are other goddesses in Hindu folklore – Kali, a beloved in Calcutta or Maari-Amma, the patron goddess of the lower castes in Tamil Nadu, just to name an assorted few. Mainstream Hinduism sometimes turns them into Shiva’s ‘spouses’, but to the people from whose histories they originate, these are mother goddesses that roam the hills, sans husband, sans marital home, but not sans sexuality. It’s hard to imagine them being slapped. Instead, in the artwork done for the campaign, their desexualised and genteel counterparts who already play daughters, wives and mothers, become sisters that now need saving.

The campaign hopes not only to shock but also to shame a society, and force it into thinking about its own pride and honour. The campaign addresses no one in particular but the collective conscience of the Indian nation. The abuse then is not about the woman herself, but about a patriarchal society’s notion of pride and shame. Perhaps this is why the makers did not choose an Apsara from Hindu mythology. Would the masses feel equally ashamed should an unmarried, sexually active, dancer be smashed in the face? In a way, it is as hypocritical as the culture of violence it seeks to address. It also plays into the western notion that Indian women need saving. In her article for the Feminist Wire, Sayantani Dasgupta writes, “It is but uncanny how well the Save Our Sisters campaign fits into Gayatri Chakravorthy Spivak’s colonialist trope of ‘white men saving brown women from brown men… Only in this case of Western Feminists’ embracing of this advertisement – perhaps it’s a case of ‘white women saving brown women from brown men.’ Orientalism was at work also during the Colonial times when the colonists sought to establish their superiority stating ‘the plight of Indian women’ as their case. This gave birth simultaneously to a very apologetic reformist movement and an angry nationalist movement, neither of which was as concerned about the rights of individual women, as it was about preserving the reputation of the society.

It also seems that the campaign was made for the neo-liberal Indian middle class that is rushing into the future with stars in its eyes. Ever since India began to ‘shine’ there has been this incessant need to peep into the future. So it is not at all surprising that the campaign moves away from the 68% of women who are victims of abuse today, and instead latches on to those that might become victims in the future. What kind of women do we want to see when India is a superpower with bullet trains instead of bullock carts, it seems to ask: battered goddesses?

From the late 1930s, as America emerged from the Great Depression, went through a World War and then competed with Russia to be a super-power, a ‘masculinised’ national conscience found its alter ego in brawny comic book superheroes who dealt with corruption, poverty, spies, aliens and anything else that bothered the nation. India of course has no need to create superheroes; it only needs to shake the tree of mythology. Since the 1980s, Shivas, Ramas and Krishnas seem to be emerging again through paperbacks and TV serials. Eager to remind us of a glorious past, they drown out all alternative narratives, destroying the richness of Hindu folklore. A single patriarchal story emerges and finds resonance with an audience hungry for a more muscular nation. The gods are beefy reincarnations that would scarcely recognise their more feminine depictions in ancient art and sculpture. Alongside them are their celestial wives, taking on more and more demure avatars: their huge hips are now down to Sizes 0, 2 and 4. Their curly hair has been through an iron. They are ideal daughters, mothers, wives who like the modern middle-class woman juggle mundane household tasks (all serials inevitably have scenes with women serving Bhojan) with exciting jobs (killing demons in this case.) Though mostly adept, they do get into stupid scrapes, often needing their ‘manly’ man to rescue them. In a sense, the Abused Goddesses campaign with its muted, docile deities plays up to this new image of the goddess, and betrays the historical tribal deities. Having no memory of their agency or their history, the goddesses in the campaign’s paintings seem trapped in an elaborate and beautiful patriarchal web. If at all these images work, they only serve to remind us that we do not want to be one of these goddesses.