Sound creates worlds in strikingly layered, different and definite ways. Sounds, in various iterations, disturb, inflict, challenge, heal, torment, arouse, invite and archive, at times all at once. Building on theories in Sound Studies by critics such as Josh Kun and Jennifer Stoever, I want to attend to sacred sounds emanating from South Asian traditions to think about how sound racialises, genders, and sexualises. By centering Abida Parveen and Falguni Pathak, two iconic South Asian musicians, I want to open up a conversation about sound, sexuality, desire, and the divine feminine. Parveen and Pathak are recognised across South Asia and its diasporas with different degrees of potency: pop music, cultural memory, nostalgic nodes of being, cathartic release, Islamic spirituality, Hindu dance, divine submission, and as soundtracks for the quotidian. Their visual and aural aesthetic representations challenge how we come to construct, hear and resist sexuality and the sacred in South Asia. To me, they offer us a way to undo the (ontological) dualities of mind and body, spirit and desire.

While both Parveen and Pathak can be said to represent traditions within Sufi and Hindi music, respectively, and each notoriously dresses in androgynous/masculine-presenting ways, I do not want to read Parveen and Pathak as simply national or religious musicians or to superimpose the mostly Western identity of “queer” or “butch” onto them, as that would be a disservice to us and disrespectful to them. Rather, I want to push further and work through the many uneven translations of what Nadia Ellis calls “territories of the soul” to hear, listen and attend to sexuality differently. I choose to study Parveen and Pathak not as a way to “queer” Islam or “queer” South Asia. Rather, I want to consider how the sound of their music pushes me to rethink my own fixation with queerness, elsewhere, South Asianness and communities of sound, what Gayatri Gopinath calls “queer audiotopias”. What does unfastening these rigid registers of reading our world open up, make audible, make possible? So, I begin with the sounds that alter my registers of time, feelings, memory, bodily fluids, frames of longing, movement and futurities. They force me to listen in ways I previously imagined impossible.

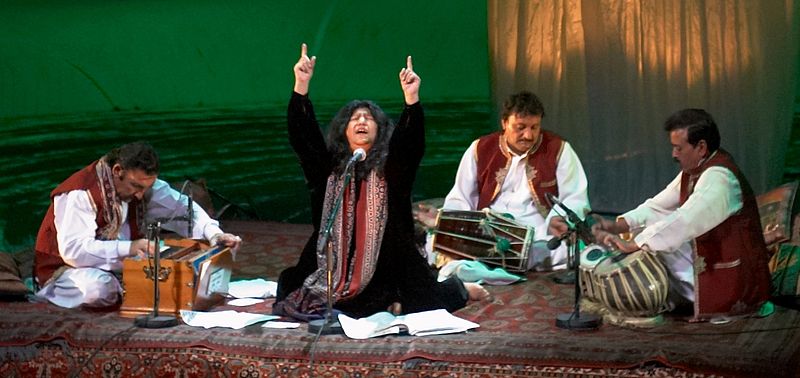

Abida Parveen, based in Sindh, Pakistan, traces her lineage to regional Sufi traditions. She is one of the few women qawwals. Qawwalis as devotional sounds are central to a South Asian imagination of Islam, peace, selfhood, and state-making. Revered as the “Queen of Sufi music,” Parveen is often dressed in what would be seen as androgynous attire. She often performs in ajrak (Sindhi shawl) nestled around her neck and draped on her chest and body. She states that in her performance, she transcends gender where she is neither a man nor a woman, and is simply a vehicle of passion and devotion who sings for, and surrenders to, her divine. In fact, in a recent interview, Parveen refers to herself as a keera makora, which translates to an insect and ant. By referring to herself with this demoted status, she directs us to the status of the human in front of the divine as one of insignificance.

Based in Bombay, India, Falguni Pathak is known as the “Queen of Dandiya” and is mainly seen in masculine-presenting clothing. She gained notoriety as one of the most sought out performers for Navratri, a nine-day Hindu festival that celebrates the divine feminine. The nine days of devotion include worship rituals, prayers, dandiya and garba. Both dandiya and garba are traditional folk dances from Gujarat and Rajasthan. Dandiya translates to “sword dance” and Garba means “womb” in Sanskrit. Pathak is the most desirable soundtrack for this epic battle of divine femininity and feminine power. Pathak’s hyper-feminine pop sensibility and masculine-presenting clothing might seem mismatched, however, sound studies scholar Pavitra Sundar argues that for Pathak’s audiences, which include avid dandia dancers, garba doers, as well as religious devotees, this was not an incongruity, nor a failure of the artist’s. This is because Pathak, unlike Parveen, is revered as a queer icon in India. Pavita Sundar states: “Pathak’s tomboyish appearance so much as the apparent disjuncture between that look and her voice that is key. What is queer about her voice is the look of it.” The look and sound of her voice, together, offer us a new way to think about how gender and sexuality transgresses existing frames while not always being totalising.

Abida Parveen’s music, and qawwalis, more broadly, has been the soundtrack of my daily life since my childhood growing up in and with Pakistan. Parveen’s music is central to my spiritual self-making, to my understanding of divinity, and my mapping of desire and love. Her vocal and visual aesthetic performance allow me to think about different ways that different bodies move in specific contexts, and how that movement is about pleasure, desire, agency, longing, submission, and suffering. When Abida Parveen sings, Mein Sufi Hoon (I am a Sufi) and Dost (Friend) she takes me to ecstasy. This ecstasy is spiritual, erotic, and sexual. Parveen’s voice opens up a space to forge a relationality with the sound of an Islam, outside of dominant ideas of hyper-religiosity and Cartesian rationalism. Her voice disrupts the bio-logic of body, sound, spirit. It is this unsynching of sound, speech, and body that she performs so beautifully. Abida Parveen does not perform within these dictates of these biologics, instead, she sits (both literally and metaphorically) like a qawwal and a qawwal sits in submission to their beloved.

Parveen’s music and performance takes place at a time when Sufi Islam is being made legible through the neoliberal logics of peace and security both by global philanthropy and international development projects and other Pakistani state and cultural projects. Because Qawwalis are a form of traditional music, whose lineage traces back several centuries, they are being revived precisely to show how peaceful, lyrical, open and musical Islam can be, was, and has the possibility to become. But I am not interested in excavating Qawwali as an essentialised frame of resistance or peace. Rather, I am interested in the potential range, texture, and substance of existence that Parveen’s aesthetics and voice specifically enable: in this Islam which is a way of life, love is non-hierarchical, multiple and queer, where your love for the divine is on the same plane of feeling and existence as your love for your lovers, and other ways of loving. Abida Parveen’s voice expands my frames of love through a spirituality that is not based in a fear of God the Father but that figures forth the divine as a force of friendship, struggle and sustenance.

Falguni Pathak’s music and music videos were also a part of my teenage years. She began her career as a playback singer for Bollywood films: Koyla (Charcoal or Charred) (1997) and Pyar Koi Khel Nahin (Love is not a game) (1999). Her first album, Mainay Paayal Hain Chankaye (My Anklets Dance With Me) was released in 1999 and made her a household name in pop music. Pathak is currently most well-known for providing the soundtracks to Navratri celebrations. Pathak has always worn masculine-coded bright coloured kurta pajamas and short hair (which she stated that she refuses to gel because it restricts the movement of her hair while she dances) yet her voice can be coded as hyper-feminine. The songs she has sung are made legible through visuals in music videos of heterosexual and heteronormative love. What I love about Pathak in the music videos for Mainay Paayal Hain Chankaaye (1999) and Meri Chunnar Udd Udd Jaaye (My scarf flies away) (2000) is that there is a triangular performance: she is a central figure in her music videos without being the central character, and the central characters are always feminine bodies. Her masculinity is not opposed to these femininities but is in fact co-created through them and their desires. The man who is the object of the protagonist’s affection and desire is only one part of the story: both music videos begin with the intimate friendship between Pathak and the protagonist who is always a woman who presents as feminine. It is Pathak’s feminine-coded voice that articulates a desire. The desire being articulated is read (read: heard as) as the protagonist’s desire. I argue that Pathak’s voice entangles the subjects of desire and desiring subjects. She disrupts how we understand, read, and hear the erotic. While Pathak’s voice provides me with a sense of queer relationality, I want to be attentive that this relationality is, indeed, also recognisable through hegemonic frames. Pathak is beloved in India, and in many versatile diaspora contexts, such as in languages like Gujarati, Bombay Hindi, in urban, upper- and middle-class communities, as well as pop, sacred and devotional soundtracks. I am pointing out that it also produces, sonically, a way to listen otherwise.

Devotional practices of sound such as qawwali, dandiya, and garba are central to mobile sonic cartographies. The frames of spirituality, sound, and sexuality are not often located next to one another, let alone analysed together. How do Parveen and Pathak rupture our reading of sexuality and desire in and from the global south and South Asia? How do their sonic improvisations disrupt, resistance, re-inscribe what Maria Lugones calls the “coloniality of gender”? What frames of world-making are made possible when we start with their sounds? By centering the work of black queer feminists scholars, Jacqui Alexander, Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley and Nadia Ellis, I ask why studying the spiritual as manifest through sound might be central to understand sexuality. This music compels close attention to queernesses and spiritualities as co-creative and how queerness is framed through Islam and Hinduism not as orthodoxy of institution and scripture, but as a way of life, a way of being in relation, a way of becoming.

Parveen and Pathak function in South Asian transnational registers of resistance and religious grammar entangled with class, caste, ethnic, gender, racial, land, diaspora, and linguistic hierarchies. These messy particularities inform feminist and queer formations and are not devoid of nation-building practices, transnational racial capital and labour, caste and class politics, and identity formation in South Asia and its diasporas. Indeed, it is within these densely populated itineraries of divinities and feminine deities that I can hear and sonically experience erotic desire. Parveen and Pathak allowed me as young Gujarati-speaking Ismaili Muslim girl living in Sindh, Pakistan to play with sound. Despite my physical location and various diasporic statuses and destinations these two artists remained central to my aesthetics and practices of femininity and queerness.

Sounds of Abida Parveen and Falguni Pathak’s force move me to other frames, that foreground unforgiven settlements. They provide me with what Jacqui Alexander has so beautifully called “pedagogies of the sacred.” Alexander’s work shows me that transnational and transgenerational memory, spiritual work, and our different claims to home are crucial to how we imagine wholeness and fleshy embodiment of the spiritual, the sexual, and the erotic. To begin this work on histories of South Asian sexualities, I centre the feminine divine and I go back. This back contains multiple temporalities, located in the kal which is an Urdu word that means yesterday and tomorrow at the same time. The sonic improvisations of Parveen and Pathak create a samaa. Samaa means listening in the Sufi tradition. As a devotional relational practice of listening, in which yesterday and tomorrow are both present are equally important, these sacred sonic constellations are central to how I listen for love and listen with love.

Cover image: Falguni Pathak, Wikimedia