“For every incarnation of Rama, there is a Ramayana”, says AK Ramanujam in his essay ‘Three Hundred Ramayanas’. So, too, there should be three hundred Ramayanas for every incarnation of Sita, the latest being in the form of a curvy, coquettish, jazz-singing Betty Boop.

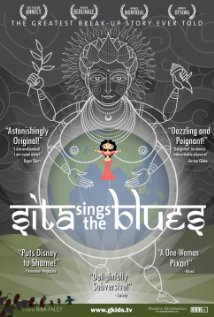

Nina Paley‘s 2012 film Sita Sings the Blues (available for free) is a wonderful, whimsical take on the Ramayana. It is now famous for its copyright struggles and slightly less famous for ticking off the self-appointed guardians of Hinduism. Told via traditional animation and Rajasthani artwork, the film portrays Paley coming to terms with the end of her marriage and how Sita’s travails mirrored her own. Apart from being, what I presume, a very cathartic experience for her, this film is also an important work as it makes the epic less of a good triumphs over evil story and more about how hard marriage really is. Even without Demon kings carrying you off to their island kingdoms.

A really great

That’s exactly where this film triumphs. Rama and Sita are no longer placeholders for chastity and virtue, but are human and they make excessive demands on each other, they are callous and take each other for granted all the time. Sita also oozes sexuality with her swaying hips and half-lidded eyes and sings those delicious Annette Hanshaw songs. I’d have never thought of putting the two together, but Hanshaw’s music couldn’t be more perfect to tell Sita’s story. Her coy, light-hearted songs (that end with a trademark “That’s all!”) are a foil to the ‘normal’ Sita we know from popular retellings of the Ramayana: Sita the Obedient, Sita the Chaste, Sita the Pious. This Betty Boop version of Sita lets herself be sad and angry towards Rama and rightly so. She’s just spent ages as a hostage in a foreign country and now she has to prove that she didn’t cheat? Oh, come on! Moral stories often conclude with the virtues of not letting anger consume oneself, but when your husband leaves you without any rhyme or reason, a good spell of anger can be very cleansing for modern women and mythical goddesses who are reborn as woman alike. Paley masterfully conveys this with a powerful Agnipariksha sequence, where the flames consume Sita, and Sita becomes the fire.

As much as it is important to make Sita relatable, it was also just as important to humanise Rama. Rama is traditionally thought of as the ‘perfect’ man, who had a great sense of duty, among many other things. But what does ‘duty’ really mean for Sita? Paley’s Rama gets no songs at all, he just blithely trips along, unable to see Sita’s distress and – literally-stomps all over her. There’s a fantastic scene in the movie where Luv and Kush are taught songs praising Rama (imagine being Sita and having to hear how wonderful and amazing your absentee husband is!). True to form, Paley’s Luv and Kush sing a tongue-in-cheek song praising Rama’s sense of justice and how he set his wife ablaze. One particular verse goes:

“Rama’s wise, Rama’s just,

Rama does what Rama must

Duty first, Sita last,

Rama’s reign is unsurpassed!”

That really does make you think. How come a wife and kids aren’t the duty of a ‘perfect’ man? Where’s the justice in an innocent Sita being exiled to a forest? At this point, we, like our imperfect narrators, come close to the trap of reading far too much of the current mores into mythology. But it is a good reminder that mythical heroes are all very well on paper to revere, to sing about, to worship and even perhaps, to gently poke fun at, as long as we don’t prop them up as yardsticks to measure ourselves.

Featured Image Credit: Blog, NinaPaley.com