accessibility

‘How can she claim to be deaf if she doesn’t use sign language?’ ‘I’m glad this film has articulated the…

विकलांगता के साथ जी रहीं महिलाओं (Women with Disabilities/WWD) को यौन और प्रजनन संबंधी स्वास्थ्य देखभाल और अधिकारों पर ज़रूरी बाचीत

अलग-अलग शौचालय बनाने के अपने लाभ हैं, विशेषकर जब कि एक जेंडर को दूसरे जेंडर से खतरा महसूस होता हो। लेकिन इस पूरे कृत्य को सामान्य बना देने और इसे जेंडर भेद से दूर करने से संभव है कि महिलाओं को, जहाँ कहीं भी वे हों, प्रयोग के लिए आसानी से शौचालय उपलब्ध हो सकें।

प्रत्येक फैंटसी या कल्पना एक बेहद ही निजी अनुभव होती है, भले ही यह मन में ही रखी जाए या दूसरों को बतायी…

केवल एक तरह से जीवन जीने, या अपनी यौनिकता को अनुभव करने से अधिक और भी बहुत कुछ होता है। इसके लिए ज़रूरी है कि पहले तो हम अपने मन में इसे स्वीकार करें और इसके लिए तैयार हों।

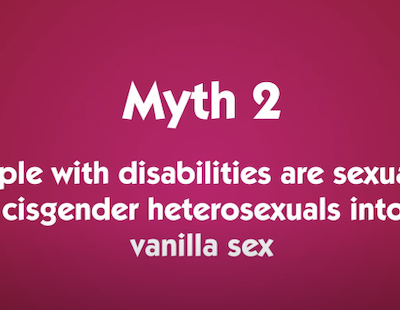

What vindicates the argument that women with disabilities (WWDs) should be deprived of sexual and reproductive healthcare and rights is scary. Harmful stereotypes of WWDs include the belief that they are hypersexual, incapable, irrational and lacking control. These narratives are then often used to build other perceptions such as that WWDs are inherently vulnerable and should be ‘protected from sexual attack’.

If the workplace looked anything like our world, it would have 50% men and 50% women, 7% would have a college degree, 55% would have access to the internet, and only 70% would have access to a smartphone.

Dr. Lindsey Doe debunks myths around disability and sexuality, at once carving out space for affirming and inclusive discussions and challenging negative and harmful stereotypes. Emphasising the sexuality of people with disabilities as rich and diverse, Lindsey wonders what inclusive sexual and reproductive health and rights really mean.

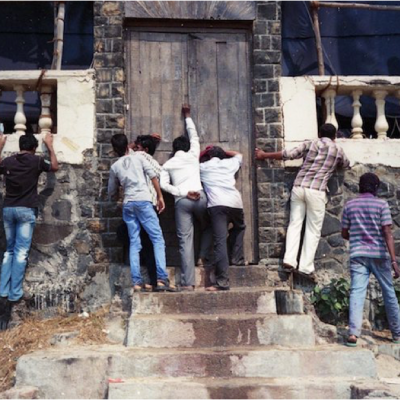

Shilpa Phadke reminds us that we have the right to choose to take risks and the responsibility to respect difference so that we can re-imagine public spaces, feel a sense of belongingness in them, and have them belong to everyone.

The First International Film Festival for Persons with Disabilities was recently organised by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment…

I said “excuse me”, walked past them and then never looked back to see the look on their faces. And then without a thought, I reached the destination and said loud and clear, “Woman’s seat”, which was a gesture to say “give me the seat, because it is a woman’s seat and you are a man sitting on it.”

I gave myself the freedom to choose. And I chose to re-examine my assumptions. Maybe it was possible to ask strange men for directions without being afraid of seeming vulnerable. Maybe I could plan my outfit without bothering about the fact that I would be travelling on public transport.

I gave myself the freedom to choose. And I chose to re-examine my assumptions. Maybe it was possible to ask strange men for directions without being afraid of seeming vulnerable. Maybe I could plan my outfit without bothering about the fact that I would be travelling on public transport.

The boundaries are the most interesting bits. No definitions can be identified without them, and yet they themselves remain in a state of flux – neither here nor there, neither this nor that, but both, all, nothing, and so much more. None can stake their claim on the borderland; it is unseizable, enigmatic, most ungraspable. In its ambiguity it has the power to comfort the outlier at its best, and at its worst, leave bereft those who seek refuge in the absolute.

We can speak of many situations in terms of access or its lack for all kinds of people, and it will always give us insight into the society we live in in two interdependent ways: one, it reveals a polarity between who is given and who is denied access, and two, it determines the big-picture human value given to the commodity that the access is contested for.