class

At present Neel[1] and I live-together, part-time. I write part-time because I stay alternately with him and with my sister…

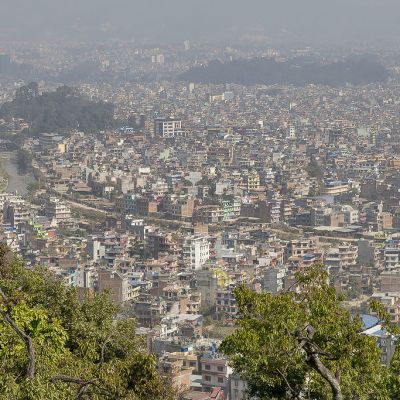

In our mid-month issue, Amit Timilsina writes about the role class plays in the decisions that young people make, and what he himself, as a young person and a youth leader, had to do to gain access to resources and to professional acceptance.

हमें इस तरह से ढाला गया है कि तथाकथित ‘विकल्प’ जो हमारे संबंधों को परिभाषित करते हैं, वे भी हमारे लिए हुए विकल्प नहीं बल्कि समाज द्वारा सृजित हैं। हालाँकि, जैसा कि हमने देखा है, इन सभी चुनौतियों के बावजूद, महिलाएँ, जब वे खुद को व्यक्तियों के रूप में महत्वपूर्ण मानने लगती हैं, तो वे अपने परिवेश और परिवार के सदस्यों के साथ बातचीत करने की रणनीति तैयार करती हैं।

Class is a very important factor if you want to associate with “smart” company. Your looks, your fashion sense, your taste in music, your knowledge about international issues and celebrity gossip become very important to belong to “that” bunch of people.

He sighs and says – aapko apni dil ki baat bataane ka mann kar raha hai (I want to tell you a secret, a matter of my heart). I nod and encourage him to do so. Aap bura toh nahi maanengi? (You won’t feel offended, will you?) Confused and immensely curious, I assure him that I will not take offense. Asal mein, mera mechanic ka kaam tha aur who theek hi tha lekin mere dost ne auto drivering karke ye seekha ki auto drivering karne se sex karna bahut easy ho jaata hai (In reality, I was working as a mechanic and everything was going fine but one of my friends who became an auto driver soon learned that it was very easy to have sex this way).

But TikTok is giving young people – particularly women – in South Asia a new avenue to showcase their talents. While for the majority of women using the app their fame is exclusive to TikTok, an increasing number are able to use it to get paid work. And for many, the platform represents a scarce opportunity for bodily autonomy, and a chance to carve out space as a performer in the face of film and fashion industries that shut them out.

अधिकांश पूर्णकालिक (और यहाँ तक कि अंशकालिक लोगों के मामले में भी) घरेलू काम के लिए रखी महिलाएँ जो पैसे कमाती हैं वह उनके काम की तुलना में न के बराबर है, और जो फायदे उन्हें दिए जाते हैं (छुट्टियाँ, स्वास्थ्य देखभाल, पेंशन) वो काम पर रखने वाले की उदारता और अधिकतर उनकी मर्ज़ी पर निर्भर है।

Fouzia Azeem, more popularly known as Qandeel Baloch,was called Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian. Madiha Tahir, a journalist and filmmaker who is interviewed in the documentary,questions this comparison. To quote her: “She (Qandeel) is not Kim Kardashian at all. She is not famous for being rich. An upper-class woman would have her class protection and it’s unlikely that an upper-class woman would be supporting her family from these social media videos.”

This stigma of caste, class and sexuality is a pervasive amalgamation of socio-cultural mindsets that take root and function in myriad complex ways, and paint working women in broad, sweeping, agency-less brush strokes.

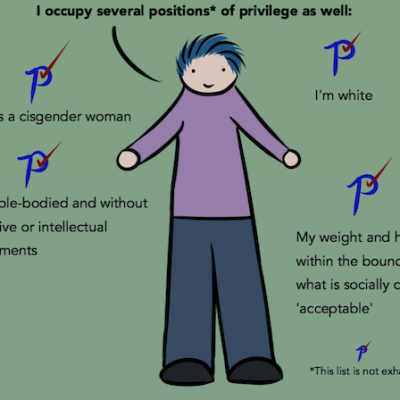

Often, we take certain things for granted, forgetting that there are certain privileges and power dynamics which we benefit from even if we don’t realise it. Though, sometimes, there are other benefits that aren’t available to us, social or cultural factors that do hinder us in some ways, we may still have areas in which we’re more advantaged than others

What follows, in the short film Chutney, is a conversation – full of eerie, evocative storytelling – which not just sheds light on the class hierarchies in the middle to upper-middle class Indian household, but also the anxieties surrounding sexuality and sexual repression within it.

Honestly, there weren’t any specific rules for the game,

Consent basics, a little humour, but no stigma, no shame.

After the underwear slips off, does the underwear brand really matter? The underwear may mean different things for different people. It may evoke desire or may hinder access.

In the course of this interview with Shikha Aleya, Chayanika Shah points out, “While decisions around gender and sexuality are very private and apparently made by each person for themselves, the material connections of community and family make this choice very contextual, and contingent on the whole social structure.”

In unpacking class as a social category through the lens of young people accessing SRHR content via an infoline it is possible to conclude that broader reach of sexuality content does enable those who are otherwise limited by material and structural constraints to develop a more expansive and informed worldview about sexuality