sexism

You don’t even realise what you’ve said until someone in the group, quick as lightning, hits you with the rejoinder, “That’s what she said!” As you’re trying to make sense of what just happened, the group dissolves into giggles.

As a generation X-er I grew up in a world that was challenging sexuality but only encountered the instability of gender as an adult in radical new academic texts which were not then yet part of our everyday narratives. My daughter born between Gen Z and Gen Alpha is growing up in a world of gender fluidity and multiple pronouns.

In the uncertainty and volatility of the pandemic, Pramada Menon examines what has changed for herself, for the world, and for the various attributes of the workplace – mentorship, conversations, power, and purpose, among others.

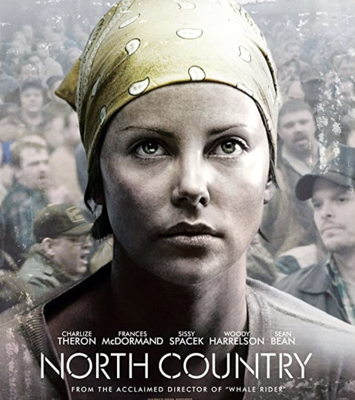

I recently watched North Country on Netflix, a movie based on a true story of a woman’s fight for equality at the workplace. It is based on the case, Jenson vs Eveleth Mines, in the United States in which Lois Jenson, fought for the right to work as a miner, and the right to work free of sexual harassment. She won the landmark 1984 lawsuit, which was the first class-action lawsuit on sexual harassment at the workplace in the United States and resulted in companies/organisations having to introduce sexual harassment policies at the workplace.

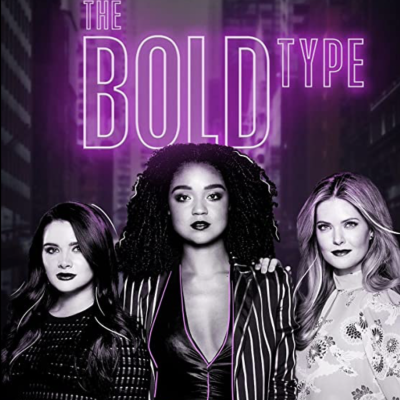

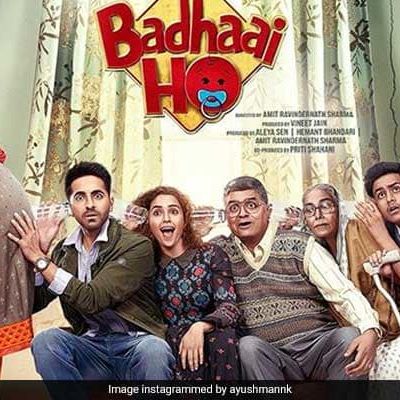

None of these characters is perfect but in their imperfections we can learn more about body positivity, gender sensitivity, privilege, consent, unconscious and implicit bias, sexuality, masculinity, their intersections with class, religion, race, age, and more.

I am not like other girls”, “I don’t like hanging out with girls that much”, “She is being very irrational today, I think it’s that time of the month”, are some common statements that you may have heard or even made yourself.

While pop culture will continue to exist in the mainstream, it also provides us the scope to create alternative narratives and/ or counter-narratives that question, challenge and unpack the existing stereotypes and norms.

It is the winter of 2013, and my father and I are sitting at an awkward distance from each other on the living room couch, our eyes trained on the television set as a popular prime time news debate discusses a subject we have never before talked to each other about – homosexuality. It is only a few days since Section 377 has been reinstated by the Supreme Court, and the television and print media bombards us with discussion after discussion on ‘alternate’ sexualities and LGBTQ rights.

While there have been many music videos objectifying women where they are shown to be given favours by men, it is amazing to note that even in a song where a woman is being refused the ‘gifts’ she seeks, the objectification of women persists.

A year ago, just ten minutes after I had landed in the Punjab and Haryana High Court. I was introduced to this young lawyer – not the least bit enthusiastic, a big critic of the law, of lawyers, of the High Court, and most importantly, of women. “Let me tell you a secret: law is not a profession for girls,” said he.

If a woman’s clothing is tight or revealing (in other words, sexy), it sends a message — an intended one of wanting to be attractive, but also a possibly unintended one of availability. If her clothes are not sexy, that too sends a message, lent meaning by the knowledge that they could have been. There are thousands of cosmetic products from which women can choose and myriad ways of applying them. Yet no makeup at all is anything but unmarked. Some men see it as a hostile refusal to please them.

In March 2015, a popular Indian comic, Abish Mathew, performed at a college festival at the National Law University (NLU)…

The Dirty Picture, directed by Milan Luthria (2011) has ushered in various debates around sexuality through its representation of sexuality…

When I first read the title of the September issue – Sports and Sexuality – I was a little taken…