sexual and reproductive health and rights

Ethical considerations and frameworks for traditional (for the lack of a better term) have had decades of debates, discussions, and revisions to have Boards of Review with similar ethics regulations (although they are still being critiqued).

हमारा मानसिक स्वास्थ्य सिर्फ़ हमारी इकलौती ज़िम्मेदारी नहीं है बल्कि उन संस्थाओं और व्यवस्थाओं की भी ज़िम्मेदारी है जिनका हम हिस्सा हैं। इसलिए हमारी सेहत और ख़ुशहाली बनाए रखने के लिए इनका योगदान ज़रूरी है।

What does it mean to hold space and extend compassion to ourselves and our communities? Rachel Cargle reminds us to ask ourselves: who would we be if we weren’t trying to survive? Similarly, what would care and vulnerability look like if we weren’t trying to survive? The anarchy of queerness constantly and necessarily resists the capitalist engineering of the Survival Myth: one that wants us to endure an isolated life instead of embracing it with the radically transformative joy of togetherness. Caring for yourself precedes, succeeds, and exists alongside caring for the collective.

… technology, when designed with love and local wisdom, can transform both climate adaptation and sexual health outcomes.

The scope for unsafe sex, as discussed earlier, extends to STIs and STDs and therefore, the feeling of ‘un-safety’ during sexual intercourse must expand itself to actively include infections as an equally important factor for using contraceptives, as are unwanted pregnancies.

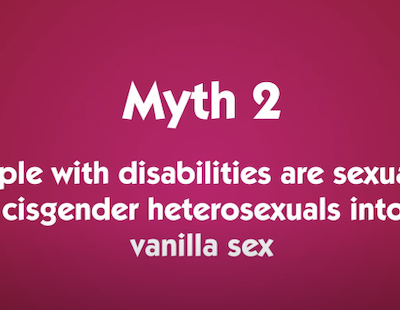

What vindicates the argument that women with disabilities (WWDs) should be deprived of sexual and reproductive healthcare and rights is scary. Harmful stereotypes of WWDs include the belief that they are hypersexual, incapable, irrational and lacking control. These narratives are then often used to build other perceptions such as that WWDs are inherently vulnerable and should be ‘protected from sexual attack’.

Japleen Pasricha, founder of Feminism in India, lays bare the violence women, LGBTQIA+ folks, and historically marginalised communities face in online spaces, ranging from identity theft, bullying, trolling, to having our private photographs and details disseminated without our consent and being blackmailed.

Dr. Lindsey Doe debunks myths around disability and sexuality, at once carving out space for affirming and inclusive discussions and challenging negative and harmful stereotypes. Emphasising the sexuality of people with disabilities as rich and diverse, Lindsey wonders what inclusive sexual and reproductive health and rights really mean.

If you live in an urban metropolitan city, you must have seen women dressed up in company uniform, carrying a heavy bag on their shoulders, their attire shouting a brand name with logos all over her. Their bodies become an advertising ground for a company’s marketing. Sometimes, the bag is a portable salon that they carry to their client’s (home), who book the beauty service using a mobile application. These ‘workers’ enroll themselves on the platform company that operates as an intermediary, to get bookings on-demand.

In a time when reason is more valued than emotion, unravelling and understanding the politics of self-care becomes all the more fundamental for us, and the movements we seek to develop and build. When our bodies, our emotions and our needs become weapons to be used against us, acts of defiance become rooted in thinking about your self and how we practice it. I find I am faced with more questions than answers, but I also know that asking the questions is the first step to finding the answers

I know that the lives of many human rights defenders are under continuous threat, that sometimes it is impossible to sleep or to enjoy a moment of peace because of the harassment coming from the outside. What I address in this text is our internal disposition as activists, and the ideas that stop us from taking care of and holding ourselves together.

Around the world, LGBTQ+ activists, queer ‘sex-positive’ feminists, sex-workers, artists and educators are leading the charge against the increasingly complex webs of regulation and censorship of sexuality online, where corporate policies intersect with restrictive state law.

Ageing vaginas in ageing female bodies are joked about. But a vagina shouldn’t have the task of pleasing anybody but itself first. To begin with, we’ll have to love and respect our vaginas in order to pleasure them. Love them just as they are. If they feel a little dry, don’t despair. Use a lubricant or a little coconut oil. If my labia are unshapely, they’re still my labia and respond very nicely to gentleness and tenderness. If I don’t love and respect my ageing body, in need of gentle, loving, patient care, then who will, for God’s sake?

To be a support system is to be a safe space for them where they can reflect upon, experiment with and understand themselves. A space where people not only come to terms with their individual selves, sexual or otherwise, but also where they become increasingly aware of their own rights.

Apart from systematic exclusions faced by individuals, evidently the mandatory use of a biometric-based digital ID has also reshaped the understanding of an individual’s agency and right to bodily autonomy. Gender and sexuality seem to no longer be matters of an individual’s right to privacy. With digitisation, disclosure of one’s gender and sexuality has become a hindrance to accessing one’s rights.