Shikha Aleya

Aspects of sexuality such as aesthetic taste, body image, sexual orientation, desires and aspirations, self-esteem, gender expression, reproductive choices, and more, are all interdependent with the impact of money in our lives and that of those around us. Indeed, our systemic relationship with money has a direct influence on how we ‘value’ ourselves.

As soon as you add sexuality to a piece about money, the first instinct generally is to reduce it all to sex, leaving the “-uality” like a little invisible tail feather that flutters away into the unknown.

Traditionally, marriage and sexuality have been bagged together and tinted with a bed-of-roses romance that has, over the last century or so, been unpacked and critiqued for propagating oppressive societal structures of gender, class, caste, and sexuality. Indeed, marriage isn’t just about two wedded souls matched in heaven, but about earthly ties that reach far beyond the couple it binds together. What happens when the roses are let out of the bag? This month’s issues of In Plainspeak on Marriage and Sexuality invite us to lean in and take a whiff.

Tolerance and space for another who is not like oneself is important. Without such tolerance and space we risk becoming perpetrators of injustice, forcing everybody into a mold that is not their shape.

What is the self, and what does it mean to give care? Philosophers, activists, artists, scientists, people of all inclinations and positions have pondered on, played with, and struggled to come to meaningful definitions about the issues these questions address. Without care, can there be a self at all?

Not everybody, everywhere, learns self-care, though most people learn how to wash their faces, brush their teeth, wear clean underwear, and lock the door to keep themselves safe.

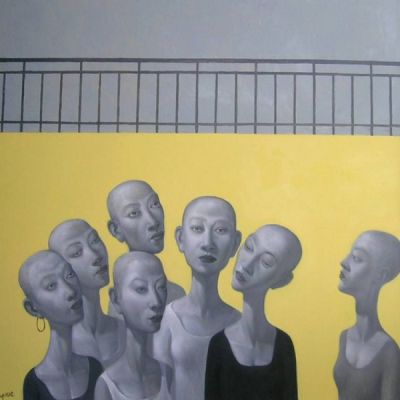

The arts hold great sway on how sexuality is viewed, represented, and understood. Does art imitate life, or life, art? Or can it be tossed away as an inscrutable mix of the two influencing each other?

There are a number of different ways to approach this theme, Films and Sexuality. One way is through the eyes of the popcorn-eating, samosa-chomping, money-paying audience member who chooses to see or not see a film, who likes or dislikes it, who makes the film a box-office hit, or pans it.

For as long as we can conceive of the existence of human civilisation, we can expect there to have been people’s movements. The term ‘people’s movements’ itself refers to the inexorable nature of the human being: things always change; they fall apart and come together in dynamic fluidity, and this uncontainable, organic spirit of constant flux is some of the joy of living.

People’s movements and sexuality. There is dissonance in this. Hugging trees, protesting dams, Swadeshi and boycott, anti-apartheid, anti-psychiatry, anti-war, child rights, flags, banners and marches. What does hugging a tree have to do with sexuality? Women’s rights, gay pride, these movements are people’s movements quite regularly seen in the frame and context of sexuality. But the others?

Fantasy is make-believe. We make something up and then we believe it in order to make it exist. However, in some contexts, the make-believe is relegated to the realm of mere ‘play’ (as opposed to the ‘real’), but there’s no denying that make-believing is a crux of human civilisation – children naturally play make-believe games that steer them in their growth, adults use the hypothetical in their thought to make everyday decisions, and both children and adults rely on fantastical stories and myths to construct a common meaning that contributes to creating the world as we know it.

The general attitude towards sexual fantasy, and the reflection of such fantasies in popular imagery, erotica and erotic porn is constructed on assumptions of ableism. There are other fantasies though, that reflect or are born of the sexuality of their creators and consumers, persons who do not fit into the accepted age, body or sexual identity.

How much do our parents teach us about ourselves? If science and psychology have proved that sexuality and sexual development grow and bloom in the course of our lives along with our other faculties, what role do our parents have in what we learn about sexuality? And, as parents, surely there’s so much we learn about sexuality, ourselves, and everything else from essaying the role? To parent is to learn how to teach what we already know, and to be able to receive more than a few surprise lessons ourselves.

As a society, in our platforms of exchange of goods, products and services, how are we approaching parenting, children or sexuality? Stores are clearly catering to the constructed parent and child. There’s lots of toys, clothes, diapers, bedsheets and cute dangling, fluffy things to cluck at in stores catering to parent and child as a combination thali (platter). The day I see personal and sexual hygiene products in a store catering to mom and a teenaged me, I will kick up my heels and bray.

Talking about migration would be talking about what happens with the crossing of boundaries. Boundaries of culture and climate, and boundaries of visibility, where a change in semantics can come to render what was invisible visible (an accent, perhaps a way of dressing, one’s values and ideas, the experience of being surveilled as an alien), while also allowing the migrant certain new freedoms to be invisible (anonymity where ‘nobody knows your name’, and certain kinds of agency one may not have enjoyed back home).