SISA spaces

My friend’s son, too, likes wearing tutus and frilly skirts. Every time they go shopping for clothes, he heads to the girl’s section and picks out the frilliest outfit. At check out, invariably the cashier asks if the pretty outfit is for his sister and he confidently says it is for him. Often he wears these outfits to school. His confidence comes from his mother’s acceptance of him and her understanding of his gender expansiveness. It helps that she is a sociologist, but there is a constant pushback from society including from his peers at school who bully the little boy. But it is the constant support from his mother and family that allows him to remain confident and thrive whilst being different.

No two human bodies are alike, and our different bodies arouse curiosity. But our fascination for the aesthetics of the perfect human body has historically created a space within art, science and religion for the examination of the ‘abnormal’ and the ‘imperfect’. As a result, some bodies are normalised while others become oddities. Freak Shows, and to a large extent, circuses and even exhibits in medical or anthropological museums particularly stand out for dehumanising and objectifying these different anatomies, and oftentimes subjecting these bodies to violence and discrimination.

I long for much more than a greater representation of brown women. I long for a complete overhaul of the racial, gendered, and economic systems that structure our suffering.

But I also long for representation of all people, including brown women, who are in love, who are loveable, and who are — in the absence of love — lonely.

Dalit women are primarily viewed as victims and survivors of various kinds of violence. Reification of the Dalit identity has led to the boxing of our existence whose dimensions are solely defined by the savarna (dominant caste) gaze. Our self-assertions of identity are commodified to create a warped limiting of our lives, creating an image that is voiceless in the minds of our potential suitors. We are not seen as being capable of desire, love or happiness; we don’t exist as individuals outside of violence.

Of course, one needs to acknowledge that this word did not magically turn up in the vocabularies of the ‘good girls from good families’ that came to a convent school to learn ‘good things’ everyday. The extensively gendered environment which promised to manufacture highly-marriageable ‘young ladies’, aided by the insistence of middle-aged spiteful teachers to absolutely destroy any kind of existence that does not constantly bow it’s pretty, two-plaited head to the heteronormative male gaze, created a suffocatingly toxic atmosphere.

While we are struggling with the vicissitudes brought on by the pandemic we are also forced to spend more time online, to look for resources in terms of health care or caregivers, to reach out to people and build a communities of care, to take a break, or to try and hook-up online for a while.

Apart from systematic exclusions faced by individuals, evidently the mandatory use of a biometric-based digital ID has also reshaped the understanding of an individual’s agency and right to bodily autonomy. Gender and sexuality seem to no longer be matters of an individual’s right to privacy. With digitisation, disclosure of one’s gender and sexuality has become a hindrance to accessing one’s rights.

We are plugged in to all kinds of data from a variety of sources, through technology, and even a window view of this space is like stepping into a global COVID control data centre. We are standing up to be counted, to be seen, to do, to contribute, to advocate, to remind, to rectify and restore, to strengthen a growing network of support and response to crisis on a scale we have neither been able to process or measure.

You see, numbers are tricky, data is tricky. More importantly, data is dehumanising. Add sexuality and intimacy to this and the waters get even murkier. Maybe it’s good to leave a few things unaffected by too much data. Maybe we do not want to talk about data and sexuality. Maybe we instead want to talk about why data around gender and sexuality must not be recorded, and instead, maybe focus on why we should honour every kind of sexual preference which is within the purview of the safe and consensual.

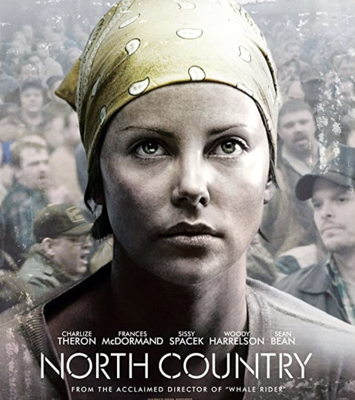

I recently watched North Country on Netflix, a movie based on a true story of a woman’s fight for equality at the workplace. It is based on the case, Jenson vs Eveleth Mines, in the United States in which Lois Jenson, fought for the right to work as a miner, and the right to work free of sexual harassment. She won the landmark 1984 lawsuit, which was the first class-action lawsuit on sexual harassment at the workplace in the United States and resulted in companies/organisations having to introduce sexual harassment policies at the workplace.

Online dating can be great fun but it comes with some risks. This quirky and in-depth Digital Security Guide by Access Now on How to Date Online Safely tells us how we can engage with fellow dating-app users while making sure we are safe from harm.

Japleen Pasricha, founder of Feminism in India, lays bare the violence women, LGBTQIA+ folks, and historically marginalised communities face in online spaces, ranging from identity theft, bullying, trolling, to having our private photographs and details disseminated without our consent and being blackmailed.

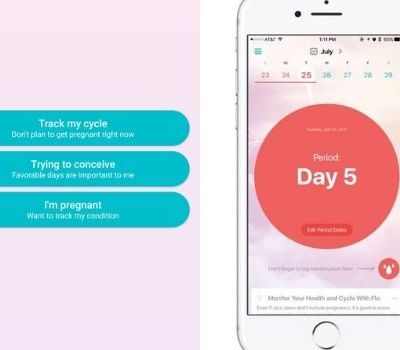

Period tracking applications can also inform you about your general reproductive health and also caution you in case of an anomaly with respect to it. As menstruators in our undergraduate years, the primary reason I saw my friends using period trackers were to keep a track of when to carry menstrual products to college or avoid the risks of pregnancy.

Vulnerability – is it a condition we find ourselves in? A state of being we choose? Let’s keep it very simple: it depends on the approach we take to defining it. In the former approach, we are ‘done to’, while in the latter we are consciously ‘doing’.

To chase down our own vulnerabilities around sexuality is a short run around the corner, five minutes ago, last night sleeping alone, with a lover, a partner who lost interest, the Insta post that leaves you feeling you’re not good enough for the hug, the kiss, the cuddle and are you perhaps the A of LGBTQIA+?