“I talk to the goddess”, said the jogappa[1], in response to my question “Whom do you talk to when you feel sad?”

It’s a question I have been asking people I met wherever I travelled in the last year. Most of the people I spoke to, however, had a simpler response: “No one”.

Some even showed confusion on their faces. “I don’t understand. Who is there to talk to? Why would I talk to someone else about my problems?” I was told.

Initially, this was but a brief glance at the complex problem of how queer communities handle a specific mental health crisis. But over the year, speaking to hundreds of community members has convinced me that the situation is serious.

I have journeyed across southern India for over a year, interviewing gay men, lesbian women, bisexual women and men, transgender women and men, intersex individuals, hijras, jogappas and many others in a quest to understand overall healthcare experience in queer communities. In particular, I’m hoping to recognise how ‘discrimination’ is experienced in healthcare settings. I’m also hoping, as a peer counsellor for the community in Bangalore, to learn how important mental health support is for the community at large, how they cope with stress, and also whom they talk to when they need help.

Mental health as priority

A cursory glance at the stories I’ve collected seems to indicate that when it comes to accessing general health services, a few people with a strong sense of identity and self-awareness are willing to challenge negative experiences occurring in medical institutions, but the majority fear marginalisation and prefer to maintain the status quo. But more significantly, the narratives indicate that accessing mental health support services (or even creating and maintaining a personal support system) is not a priority for queer people.

The latter finding is nothing new; public health studies over many decades have indicated that while seeking healthcare is not a high priority for most middle and especially lower socio-economic classes in India, seeking mental health support rates even further down the scale. Mental health services are considered important only for those with serious problems: schizophrenia, accident-related trauma, congenital neurological disturbances or other such conditions. We still live in a social context where, on the one hand, government leaders acknowledge the mental health crises in India, and on the other, individuals who are recommended counselling or therapy say, “Why should I get counselling, I’m not mad!”

The low prioritisation and limited access to mental health services affects queer communities in more marginalising ways. We already know that regardless of class, caste, religion or other social identities, queer individuals experience harassment both directly and indirectly because of their gender or sexuality identity. Beginning with the family, schools or colleges, workplaces or neighbourhoods, cinema or popular literature, and even daily interactions, all are sources of stress. It’s almost impossible not to be mentally affected by this. But if access to mental health support is not promoted as a priority, or the members of queer communities experience additional harassment in healthcare settings owing to their identities, then there is a vicious cycle created between needing mental health support and not willing or not being able to access it.

Stress and distraction

The question of how queer communities deal with stress is a more complicated one. Firstly, many of the coping mechanisms that queer people who spoke to me adopted during times of stress are usually distractions. Television, cinema, literature, music, alcohol, cigarettes, drug use, sex, dance, parties and so on, can each provide temporary relief to our stressed selves. But if one repeatedly seeks these practices of distraction they become a mechanism to avoid stressful situations rather than helping to resolve them. Moreover, if the distraction is an addictive substance it can become an additional stressor. And in more serious situations, even self-harm becomes a distraction practice that can cause physical and psychological trauma and needs immediate medical attention.

Secondly, the lack of a fundamental understanding of life-skills renders even the simplest stress factor into an insurmountable obstacle. Many of the people I spoke to, including past and current clients in my peer counselling practice, seem to struggle with problem-solving, communication, coping with loss or rejection, self-awareness etc. all of which are very basic, but very essential skills to have as an adult. The way families in India control their children’s gender and sexuality journeys while ignoring ways to help prepare them for other social stressors makes the problem that much more acute for queer communities.

Talking with someone

It was, however, the community’s consistent refrain of having “no one” to talk to, that made the problem of mental health crises stand out during my conversations. Yes, many of them had friends and other community members to spend time with and have fun with. But when they had to cry or when they felt really sad, they did not ask for help from either friends or community. And they placed little value in talking about their stressful situation with a mental health professional, a peer counsellor or even a friend from the community. The belief was that talking would solve nothing because the situation would not get any better. Stressful situations were considered to be beyond intervention, even by their friends. And they didn’t think that spending time with friends who couldn’t help was beneficial. The underlying implication was: Why ask for help, when everyone is helpless? Distractions, therefore, just made more sense.

While many distraction practices may certainly help in building resilience, they do little to help confront or resolve stressful situations. Speaking out about the stress helps in reducing its impact on mental health. Sharing one’s story with a group of friends or peers who have undergone similar experiences can be incredibly empowering for members of queer communities. Some studies show that social support and community connectedness can actually help lower depression or anxiety[2] and others have shown that even people with serious mental illness can benefit from interacting with peers and sharing personal stories and strategies for coping[3].

My own experience with support groups like Good As You in Bangalore, and with several clients whom I referred on, was that talking with people who are like oneself, or going through similar experiences was greatly beneficial for one’s mental health. Studies have shown that better mental health is linked directly to improved physical health and increased resilience and better access to social or psychological resources[4]. That means, the more relief one feels from sharing their story, the greater is the benefit for overall health, and the more the likelihood of dealing with newer stressful situations in better ways.

But in my case, and the case of several of my clients, it was also the repetition of the sharing process that seemed to help. Seeking help from professionals, sharing our story with friends, and relating our experiences to other queer individuals made the journey easier. There was value in learning from others’ experiences with the same stressful situation. One study reviewing peer support literature found that peer support groups or networks helped promote hope and belief in recovery, increased self-esteem and self-management of difficult situations, and thereby also increased social networking[5]. So there is great personal benefit in reaching out to peer groups. There is also value in seeking medical intervention from sensitive healthcare professionals where available, and peer networks can help in linking with such professionals.

So the simplest way to handle a stressful situation and learn ways to cope is to talk. Talk to someone: a friend, a peer counsellor, a telephone helpline, a counsellor on Skype or on chat, or a personal visit to a psychologist or therapist, whichever is affordable. Or find a group of friends to spend time with and talk to at any time. Or visit a support group, however basic the group might be. Just being part of a group of people with whom one has something in common can help reduce stress levels. Do any or all of this, and remember that it’s not really about things getting better, it’s about you getting better at coping with things.

_____________________________________________________________________

This article is partly based on a research study examining healthcare discrimination among non-normative genders and sexualities, for TISS, Mumbai. Many thanks to Anurag P Nair, Research Assistant, TISS Mumbai, for reviewing this article.

***

[1] Jogappas are a sub group of transgender women from northern Karnataka and parts of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra who are dedicated to the Goddess Yellamma, similar to devadasi women in the same region. Jogappas are male-born, but take on women’s identities and attire and spend their lives singing and seeking alms .

[2] Pflum, S. R., Testa, R. J., Balsam, K. F., Goldblum, P. B., & Bongar, B. (2015) Social Support, Trans Community Connectedness, and Mental Health Symptoms Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults, in Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity Vol. 2, No. 3, 281–286.

[3] Naslund J.A., Aschbrenner K.A., Marsch L.A., & Bartels S.J. (2016) The Future Of Mental Health Care: Peer-To-Peer Support And Social Media, in Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences (2016), 25, 113–122.

[4] Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H.-J., Bryan, A. E. B., Shiu, C., & Emlet, C. A. (2017). The Cascading Effects of Marginalization and Pathways of Resilience in Attaining Good Health Among LGBT Older Adults. The Gerontologist, 57(Suppl 1), S72–S83.

[5] Repper J., & Carter, T. (2011) A Review of the Literature on Peer Support in Mental Health Services, in Journal of Mental Health, August; 20(4): 392-411

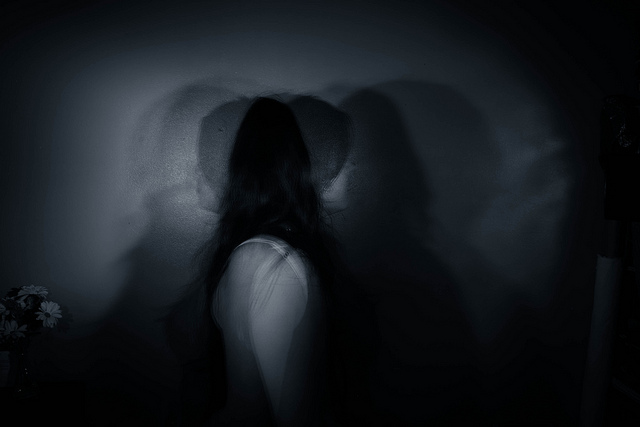

Cover Image: (CC BY 2.0)/Flickr