“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”

Leo Tolstoy

The year 2014 as the 20th anniversary of the year of the Family [1] resulted in many discussions around families, their role and their importance in every single person’s life at different fora, including the International Policy Spaces like the United Nations Human Rights Council and others. At the Human Rights Council, the resolution on “protection of the family” tried to narrow the definition of families to that of traditional families, and simultaneously treated this family unit as the rights holder jeopardizing the rights of individuals within the family. The family as an institution is always taken for granted and unpacking the concept of ‘family’ is a territory very few people will tread upon. At the centre, the family is an informal agreement of regulation/control of sexuality, especially women’s sexuality.

Sexuality and the family share a very dysfunctional relationship. ‘The family’ and ‘sexuality’ are extremely complex in the way they play out in each individual’s life. Both of them constitute myriad emotional conundrums and let’s face it, much heartbreak. It then is not surprising that the one word that commonly haunts people with respect to both is ‘acceptance’ – acceptance of sexuality by the family, acceptance of ideologies and politics of family members when they are different from one’s own, acceptance of one’s own sexuality in the context of the traditional family set up, and so on and so forth. Feminists however have contested this idea of acceptance in the context of sexuality and desire and have rightly tried to shift the debate away from acceptance (which presupposes someone who is better/normal to accept someone who is a problem) to freedoms. And this links the other element common to both the family and sexuality, which is also cause for disagreement – ‘choice’. Do we have the choice to decide who we are and whom we desire? How we conduct our sexual lives? And do we have the choice about who is in our family? More importantly would it matter if we did have that choice? Would our families and the way they function change?

In this myriad complex of emotions, one can say the influence of the family over our sexuality is confusing and contradictory to say the least. On the one hand, marriages especially arranged marriages are fixed by families, particularly parents, which effectively mean that families decide who an individual must have sex with. Similarly when a girl reaches puberty, the rituals and customs while objectifying her are also an open declaration of the fact that “she has become a sexual being and that she can reproduce.” They do not necessarily take into account her own experience of sexuality, which could be different from this normalised timeline. Reading this in a broad, optimistic manner, it is a celebration of a woman’s sexuality albeit linked to reproduction in a hetero-patriarchal manner. But this comes with a caveat – the family gets to decide the way this girl experiences her sexuality more specifically through marriage. But when this sexual experience is outside the ‘normative marriage framework’ (same-sex, inter-caste, inter-religion), the consequences are often dire. Additionally, sexual violence within families, including child sexual abuse or sexual abuse of adults by family members, is hushed up. In the latter, the violation and the silence surrounding it often leads to very traumatic consequences. One would then conclude that the only conversation on sexuality within a family would be in the context of marriage. Marriage is also the foundation of the traditionally accepted family in the sense that marriage creates family. Marriage then ‘legitimises’ one’s sexuality in the same way a marriage is the beginning of a ‘new family’. Consequently, an effort to discuss sexuality outside marriage is not only seen as a ‘perverse’ act but also as a threat to the very foundation of our society, marriage through which families are born and created sometimes artificially and forcefully.

The recent controversy in India on the Women’s Empowerment video by Vogue – “My Choice” opened a can of worms with respect to issues of representation, empowerment, neo-liberalism and women’s rights. While this article does not intend to look at these issues, one specific sentence in the video and the reactions to it is very relevant for us namely, “sex outside of marriage – my choice”. This particular sentence evoked critiques from everywhere and a common point of reference was that the video promoted “adultery”. While there was no consensus on the interpretation of the term “sex outside of marriage” the outrage around this particular sentence describes the relationship between traditional family and sexuality very aptly. In the more recent case of the AIIMS doctor who committed suicide citing her husband’s homosexual orientation and dowry harassment as the reason, “marriage” took centre stage. Discussions and articles by many activists questioning the idea of marriage has become a part of popular media as well. While everything related to marriage is all said and done in the feminist circles and feminist critique, there is a need to look at “marriage vis a vis family” linked to sexuality. Families are traditionally built around controlling women’s sexuality, which is linked to reproduction and further to the way property is inherited and the devolution of this inheritance.

In both the cases mentioned above the ‘sanctity of marriage’ clearly came into question and in the latter with rather terrible consequences. The first instance – Vogue’s video – created a furore. People on social media and elsewhere were quick to come to the conclusion that the statement on sex outside of marriage was condoning adultery. Even if one were to assume that they were speaking about adultery (which is a hypothetical situation), adultery is neither new nor were people hearing it for the first time. Yet the idea that a woman can choose to have sex outside marriage seemed more problematic than say ‘a drunken mistake’! Moral judgement around sex outside marriage including adultery is so steeped in our society that even the State deems it necessary to regulate it, be it through criminal provision in the Indian Penal Code [2], denial of maintenance [3] and provision of divorce (where adultery is seen as fault)[4]. In cases where maintenance is denied, the routine allegation by the husband was that “she was adulterous”. Experts believe that sexual purity became the norm for the sake of keeping the bloodline safe and properties intact.

Sexuality then in the context of marriage within the confines of ‘respectability’ or of starting a family appears to be less threatening. The movements in some countries for gay marriages are a testament to this fact. This could be perhaps the reason for some queer movements, pushing for an agenda that is geared towards talking about respectability and families rather than the right of sexuality. Perhaps this is also the reason for the increased momentum in pushing for ‘same-sex love’ read as long-term, marriage-like relationship, and not desire and/or sex which might not necessarily lead to marriage or couple-dom. It is also perhaps the reason for the simultaneous higher vilification of sex work which is sex that is transactional and does not necessarily lead to a “family” or “respectability”.

Not all marriages feel contrived, but is it still important to question the hegemonic discourses and systemic structures that all of us have built and continue to perpetuate; that any sexuality outside of marriage and consequently outside the traditional family is seen as an aberration or as ‘the other’. The stigma and the loneliness around non-normative sexualities would perhaps reduce not by normalising the queer but by queering the normal. And this requires not only delinking marriage from sexuality, but also delinking marriage from the family. By this I mean exercising choice, in not only who we desire and have sex with but also who we share our lives with – not necessarily within the framework of a marriage or marriage-like relationship. This choice in many cases might mean – we choose the same people we already share a familial bond with but without the element of coercion of any sort, be it emotional, financial or physical. Consequently we need to ask ourselves: What are we afraid of?

Acknowledgements from the author: A big thank you to Meenu for reading this and providing inputs.

Footnotes:

1.The International Year of the Family, 1994, was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly, in its resolution 44/82 of 9 December 1989.

2.Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860

3.Section 125 Criminal Procedure Code, 1973

4. Section 13 (1)(i), Indian Divorce Act, 1896, Section 13 (1) (i), Hindu Marriage Act 1955, Section 32 of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, The uncodified Islamic law also provides divorce on the ground of adultery

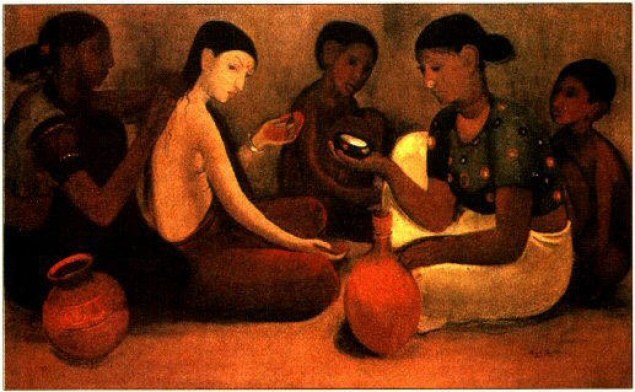

Pic: Painting by Amrita Sher-Gill (Public Domain in India)

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें