Details of a narrative are coloured in, all around us, through attitudes, conversations, news, social media, emotional, intellectual and psychological engagements, barriers to the unknown, invisible and unheard that enable a deepening of mainstream narratives.

The lesbian with short hair is the man.

The wife wears the pants.

Nobody will marry a Down’s Syndrome.

These criminal tribes make the area unsafe!

Children must learn to respect their elders.

This will happen to every Nazi prostitute.

Fragments come together and make up multiple narratives.

- A number of stories, myths, truths, beliefs and value systems – circulating over time, generations and story tellers, within families, circles of friends, communities, countries, and political, social and cultural groups – will make up a narrative.

- The stories may be different, but a narrative becomes one large story full of words, images, ideas, advocacy and propaganda, driven by those who buy into it, feed off it and add to it.

- Or seek to question and challenge it.

Before we continue:

Short hair on a woman is attached to many kinds of narratives – remember Mahsa Amini.

The statement about the Nazi prostitute does not go back to 8 decades ago, it emerges from accounts last year, of conflict related sexual violence (CRSV) by Russian soldiers during the Ukraine conflict.

There are different narratives around these words and attitudes where lie hidden worlds of codified feelings, justifications, a reason to buy or not buy into injustice, or othering. This is true of many key words and phrases across languages, as well as images, tropes and approaches surrounding us, building narratives, all the time, everywhere.

There are so many issues with the statements with which this article begins, the identified fragments of the narratives that shape many of our direct, indirect, primary and vicarious experiences, it’s hard to know where to start.

So it’s okay to begin anywhere in the layered, interconnected circles of stories. Let’s check out a story that should be simpler.

Cow katha

There are those of us, including the writer of this article, who like cows very much, being appreciative of their peace, calm, gentleness and beauty. Their right to exist, chewing the cud, a simple life.

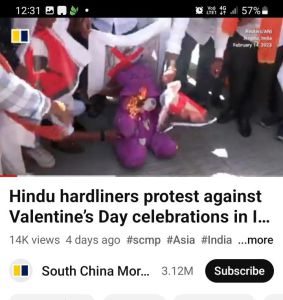

Our country and its cows have recently been in the news, over an attempted rebranding of Valentine’s Day.

The plan did not go through.

Instead, a purple bear was burnt by Hindu hardliners in Nagpur, India, this year.

The purple bear was a stuffed toy, thank you.

The image of a stuffed soft toy bear is part of other narratives, some of which may be found in windows of shops with sparkling hearts for sale at ridiculous prices.

Hug real cow or burn soft toy bear – humans and their narratives create of this world what they will, to extract what they will, whether from cows in February, on the 14th, or cows any time of the year that may be cuddled by families for 500 bucks, presented as cow cuddling services. Cow therapy.

Of course the legitimacy of cow cuddling is researched, rooted in easily Google-researched concepts, and narratives, around Animal Assisted Activity and Animal Assisted Therapy.

What part of the story is sourced from which layer of enmeshed narratives

- that connect with mental health, love, therapy, human-animal interactions?

- serving what purpose?

These are questions that no longer allow a cow to simply chew cud.

- This makes things particularly volatile when the subject is sex and sexuality.

Sex, sexuality and stories

Ah. Looking for porn?

Got you.

Got what?

Looking for porn.

So?

There again. Narratives. In just these sentences a range of feelings are evoked that could include anything from guilt to humour, fear, embarrassment, anger, confusion, rebellion and moralistic reactions. All of this is part of a narrative around sex and sexuality that most often leads straight to an uncomfortable zone. Delete your Google search history, even if you’re doing ‘legitimate’ research on reproductive health and rights.

What are the narratives around sex and sexuality? Pornography? Erotic art and writing? What makes one more acceptable than the other?

What is the significance of words like art, industry, commerce, exploitation, rescue, consent, livelihood, morality, family values, trafficking, violence, spirituality, sex and pleasure?

What about the images often attached to these, in media? And in mind?

More importantly, what is the power that these words and images hold, that make them such powerful tools for any agenda?

Words and images are amongst the basic building blocks of narratives. The language and culture in which these exist codifies our feelings and philosophies – and like instant noodles, we get a shot of sugar when we encounter them. And then there’s a high, a zone that amps up whatever is desired to be amped up. A call for peace or a call to attack.

Experiencing the narrative

Beyond words and images that evoke thoughts and feelings, there is action, engagement and dynamics. There is personal experience, political and social drivers, and economic imperatives. The narrative is born of these and other elements.

Sexuality is amongst the central strands of identity, influencing every aspect of our lives. And we live in a world of narratives. It is wise to pause sometimes and consider who we are, what we are buying into – and why.

The binary narrative is the first, most commonly experienced example of an exclusionary and traumatizing space. While it operates across everything, a look at the universal theme of health and wellbeing reveals barriers to wellbeing. As just one example, this binary approach in hospitals and health care facilities is responsible for the systemic exclusion of persons who don’t fall in the binary, right from the stage of filling forms. Medical staff are confused and disrespectful with no awareness of or sensitivity towards possibilities such as a pregnant person who identifies as male.

Or consider a few aspects of the marriage narrative.

The cis-het romance – out-of-marriage, or with VAW or inter-faith elements attached to it. There is a world of debate around live-in partners, domestic violence and why some people put up with it, why others perpetrate it, and recently, there has been set up a committee in Maharashtra to investigate inter-faith marriages.

The divorce – of those who fought for the right to marry. When this has involved queer folk, in countries where the right to marry was hard-won, news of divorce amongst a queer couple becomes bigger than news of divorce between a cis-het couple.

When a woman with disabilities chooses to have children. This has everyone expressing an opinion, and historically the most opinions have probably been expressed by those without lived experience of disability. They have shaped the narrative.

Couples who choose not to have children. Should we pity them? Take either or both to a reproductive health clinic? Counselling? Are the animals they live with, their dogs and cats, really just a ‘substitute’ for the human babies they ‘sadly cannot have’?

Marriage narratives can fill volumes – if the narratives are allowed to exist.

Narratives exist through an experience of them.

Not all experiences are permitted space, expression and open discussion.

Then what happens when there is no narrative?

Does the experienced experience not exist?

There’s another thread to pull, from tribal and indigenous weaves. Couples who stay coupled for as short a time frame as a few days, and choose multiple sexual partners, such as in the Ghotul system of the Gond and other Adivasi tribes, where young people spend time together in a form of dormitory arrangement. While some may consider this unusual or uncommon, it would be good to remember it is neither unusual nor uncommon for the communities where it is common practice. Delving deeper means we find lessons we were not taught, such as about affection, cooperation, responsibility, a sense of community and respect. The narratives we know teach different things and some of those things are worth a re-think, consider for example, honour killings, stalking, possessive and homicidal jealousy.

Of rights and rebels

In this article recently published online, Alice Barwa writes: “While reviewing my niece’s class seven English state book of Chhattisgarh, I came across a chapter titled “Dear Diary…”, which narrates from a child’s perspective their visit to Bastar, where the writer has reduced the people of Adivasi communities of Bastar to props on the roadside as they write, “…the Bastar tribes in their traditional costumes add to the natural beauty of the region.” The text provides no social or cultural context to the readers and reduces Adivasis to something exotic, which was one of the ways Adivasis were viewed by anthropologists during the colonial era. This act of “othering” often results in young Adivasis disassociating from their social identity.”

Alice’s article appears in the 2022 edition of the journal, ReFrame, that challenges the existing narratives around mental health and enables space for unheard, untold and unknown narratives. While her observation of the reduction of Adivasi communities to props and exotica is in the context of mental health and climate justice, this reductionist approach explains the invisibility of the narratives we don’t know exist.

The reductionist approach towards a person with disability for example, is one we are familiar with now, to some degree. This familiarity is because those with lived experience of disability, rights advocates and disability rights activists, have for decades, in different ways, given shape to a narrative that reflects the diverse life experiences of people with disabilities.

In this article, Nu, the founder of Revival Disability India, explains one of their experiences with narrative: “I had had the opportunity to write about my experiences of disability and chronic illness before. But I always felt people wanted it written in a very specific way — a way that would inspire the able-bodied. I draw power from my experiences and I wanted to write about what it is like navigating life as a disabled, queer, non-binary person,”

Blogger Bohemian Bibliophile points out, “One does not often understand the enormity of a situation until it is experienced in close quarters” and goes on to recount a specific incident about “being talked down to in a rather condescending tone on why I was expecting an elevator in a two-storeyed courthouse building. When informed that my mother used a wheelchair, I was matter of factly told that I could easily find someone to carry her to the first floor. After all, it was just a flight of stairs.”

An expanding universe

The universe of narratives expands at many different points in different ways, and it is either powerfully inclusive, or it is unjust and incomplete. Narratives can cause deep and persistent harm, for they are born of the environment, contribute to the environment and are the environment.

Harsh Mahaseth looks at Indian cinema using the lens of disability and gives ready examples of both harm and inclusion. Commenting on a 2016 film called Housefull 3, Harsh says : “In this movie there are three nondisabled men who pretend to be blind, deaf, and a wheelchair-user, all just to marry three rich girls, whose father stipulated the condition to marry them off only to disabled men. This movie is full of insensitive dialogues such as: “Sab kuchh chal raha hai sirf main hi nahi chal raha hun” (Everything is moving except me). When asked about the criticism faced by the movie, the directors unashamedly said: “If the janta (public) is happy, then that is the ultimate high.”

Abha Khetarpal in her article So How Has Indian Cinema Portrayed Women With Disabilities? has remarked on how “Movies have women characters with disabilities with different motives. One of such objectives is to highlight the dauntlessness of the male character”. She mentions the “recurrent theme that marriage of women with disabilities is a burden of marriage for the males around her’, and, as she points out, “Women with disabilities are also shown as at risk of sexual exploitation. Unless there is the presence of a strong male, she is not sufficiently protected.”

Expanding the narrative universe in another direction while foregrounding themes that include disability as well as sexuality, this article tells the story of a gay man who says, and this is very significant, “If I met my younger self today, I would tell him ‘just try and survive school. It will get better. Just stay strong.’”

So one can shift this narrative to ask why the focus on surviving school, when schools should be nurturing, safe and inclusive? Or are we saying schools should only be nurturing, safe and inclusive of some children, but not all? And is this the reason that the many political and social attitudes to comprehensive sexuality education, CSE, have created a narrative where children and young people are seen as incapable of engaging with sexuality?

So. Narratives and sexuality.

Approach sexuality in any person’s life and there’s an accepted narrative plus the other, or others. These exist, but are dismissed, rejected, unknown, the legitimacy of those experiences subsumed in the large, powerful wash of the allowed narrative. It may not be possible for many of us to take a stand in our personal lives – but it is possible to know that some people are taking a stand. The silent shift in support of this, the one that happens within, is as powerful as the one that waves a flag at a parade.

We have choices, the narratives are slowly revealing themselves around us, within us, in our families, our relationships, on social media, in the acts and omissions of legal and political agendas. We have choices. And while it may not be possible for many of us to exercise those choices, it is always possible to be open to understanding the unknown narratives.

There is no single narrative. It is possible to know, embrace, and respect that.

Cover Image: Photo by Daniel Olah on Unsplash