Sex has always been at the core of HIV and AIDS since the virus was first identified almost 30 years ago in India. The Indian government’s initial response to HIV and AIDS was dismissiveness/denial because Indians apparently don’t have sex unless it is of the married and monogamous kind! This was followed by the alarming propaganda that “AIDS kills” that led to stigma and prevention programmes associated only with certain groups, as if it’s a cardinal sin to be infected.

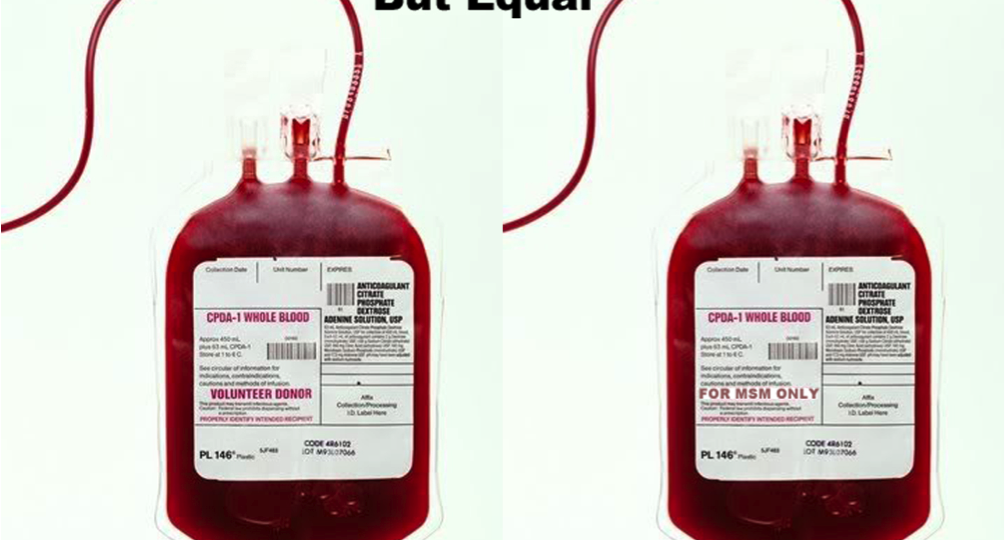

How can these prevention programmes work if they are targeted at people involved in practices that are seen as illegal, and have to be ‘chased down’? Three extremely stigmatised and invisible (due to criminalisation) core populations, intravenous drug users (IDUs), male and female sex workers (SWs) and men having sex with men (MSMs), were targeted by the government under the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP).[1]

In India, there is a general perception amongst MSM that unprotected anal sex, still termed as ‘masti’ (recreational activity or fun) as opposed to ‘real sex’, is not a high-risk behaviour, even though 55% of MSM in India have frequent anal sex and only 5-20% of them use condoms for anal sex, and very few seek medical help or check ups for Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Among MSMs, there are self-identified gay men, kothis ( men or boys taking on a ‘feminine role’ and are receptive partners), panthis (insertive male partners in anal or oral sex), and ‘double-checkers’ (men who can be both insertive and receptive partners). MSM is considered more of a behaviour than a sexual identity because among these individuals same-sex behaviour may be situational and does not exclude sex with women or traditional marriage. It is highly incautious of the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) to be obsessed with kothis or effeminate men when the bridge population of bisexual men (MSM) is not only engaging in high-risk unprotected sex, it is also mobile, diverse, and reaches across every social status and age group. Such complexity is lost in a ‘one-size-fits-all’ system which favours organisations/programmes with no understanding and experience in work with MSM.[2]

Although findings from the Independent Impact Assessment Study – 2 shows that NACP is steadily halting an HIV epidemic in India over the period 2007-2012 through its prevention programmes (that are actually single-dimension modalities[3]), on the contrary, globally, India still ranks third in the number of HIV infected people in the year 2010. To make things even worse, in 2010, NACO showed a decline in trends in prevalence rates among MSM (4.43%), Transgenders (TGs) (8.82%) and IDUs (7.14%).[4] There has been no prevalence data on MSM post 2010-11, which prompts us to assume that by showing a decline in trends, NACO is trying to wash its hands off MSM. The prevalence data seems all over the place, and random numbers that are flung around further stress on very few and spurious quantitative studies that have been misleading the government to plan its public health budgets and prevention strategies.

The government HIV and AIDS prevention programme needs to form allies with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and community-based organisations (CBOs) for their active co-operation and for their programmes to move forward, as NGOs and CBOs are the frontline in HIV and AIDS prevention that deliver services through targeted interventions. What is further upsetting is the fact that MSM outreach workers themselves have fallen prey to abuses and threats, let alone the MSM community. In Nepal, there have been cases where police have beaten peer outreach workers for attempting to distribute condoms. In the Indian situation as well, police have used the fact that same-sex behaviour is illegal to harass outreach workers and interrupt prevention activities.

It is important to underscore that these organisations need the co-operation of police and other local government institutions to ensure the safety of outreach workers and MSM, the latter of who are more likely to avoid participation in these programmes due to harassment and stigma. Government-based health facilities need to be sensitised and trained, as clinics for STIs (sexually transmitted infection) transmitted through oral and anal sex do not exist, and STI doctors are not culturally sensitised to MSM issues. There is also an urgent need for a national policy and action plan to address barriers to Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) access at individual level among MSM. MSM experience barriers to ART at family/social, healthcare systems and individual levels such as lack of family support due to estrangement, discrimination, and lack of support within aravani (transgender women) and kothi communities fearing loss of emotional and psychosocial support from their own community if their HIV-positive status is revealed, negative experiences with health care workers at government ART centres, and inadequate counselling services and lack of confidentiality at the ART centres.

Following the dramatic announcement of antiretroviral roll-out in India[5], the priority to provide first-line drugs was for HIV-positive people referred from targeted interventions, seropositive[6] women, particularly those who have participated in the PPTCT (Prevention of Parent-to-Child Transmission) programme, infected children, and those below the poverty line. Access for vulnerable populations such as SWs, MSMs, and transgender people as well as those living in rural areas has been extremely limited. Not to forget—by limiting ART to those with a CD4 count[7] of 200 or less, the government is effectively making people wait until they are ill enough to qualify for treatment. (ART should instead be recommended for all HIV-infected patients regardless of their viral load[8] or CD4 count. Viral load should be made the main indicator of initial and sustained response to ART and should be measured in all HIV-infected patients at entry into care, at initiation of therapy, and on a regular basis thereafter.)

The prime need of the hour is deleting or reading down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code on sodomy, de-criminalising sex work, and altering narcotics control by cracking down on trafficking instead of punishing end-users to whom treatment should be provided for substance abuse. That way, stigmatised behaviours like anal sex, intravenous drug use and sex work can be open table talk and can lead to actual communication between those working with HIV and AIDS, and those who view HIV and AIDS as a problem to be tackled within the health system.

[1] Refer to page 10 of To Halt and Reverse the HIV Epidemic in India.

[2] Refer to pages 12, 13 and 14 of To Halt and Reverse the HIV Epidemic in India.

[3] Single-dimension modalities include condom distribution, HIV education, voluntary HIV counselling and testing, and the treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). There is a lack of multi-layered approach to address the unique needs of MSM such as socio-cultural issues, co-occurring mental health issues and stigma among health workers, policy-makers and the public.

[4] Refer to fig. 2.3 of page 8 of NACO’s 2012-13 Annual Report.

[5] Refer to page 114 of NACO’s Strategy and Implementation Plan (2006-2011).

[6] Giving a positive result in a test of blood serum, such as for the presence of a virus.

[7] A CD4 count is a lab test that measures the number of CD4 T lymphocytes (CD4 cells) in a sample of your blood. In people with HIV, it is the most important laboratory indicator of how well your immune system is working and the strongest predictor of HIV progression to AIDS.

[8] A viral load test is a lab test that measures the number of HIV virus particles in a millilitre of your blood. These particles are called ‘copies’. A viral load test helps provide information on your health status and how well antiretroviral therapy is controlling the virus.