I felt very uncomfortable the first time I saw the Dove ‘beauty sketches’ campaign ad or the ‘most watched ad ever’, last year. My discomfort became more apparent again this year when a stimulating discussion with a friend on a weekend trip turned sour when I was confounded by my inadequate explaining of how regressive and counter-productive the campaign actually was. The random musings in this piece emerged out of that inability to voice my displeasure.

Even though I pride myself on being a cautious and suspicious recipient of corporate sponsored media images that perpetuate certain ‘desirable’ ideas of female physicality, my instant reaction, too, of course, was buying into the feel-good sappiness the ad promoted that we are more beautiful than we usually give ourselves credit for, asking us to be ‘grateful’ for all the nice people out there who tend to look beyond one’s supposed physical flaws. The message, no doubt, was uplifting. After seeing innumerable friends share the video on social networking sites, I watched it a second time, and this time I was supremely unimpressed and a little annoyed and then angry.

The ad, again, plays on the same set of rigidly defined notions of female beauty. The participating women in the ad described themselves with ‘negative’ markers like being ‘fat’ or ‘round’ and started to tear up when the other participants used ‘positive’ markers to describe the same women, like ‘pretty blue eyes’, ‘thin face’ and ‘cute nose’. Wow. As a woman who is none of those things, I am conveniently excluded from Dove’s campaign and led to believe that I possess no ‘real beauty’ or in any case the ‘beauty’ that Dove seems to promote as the ‘real’ one. But then again, I was expecting much sensitivity and sanity from the same parent company that thrives on misogynistic campaigns for Axe deodorants and Fair and Lovely creams.

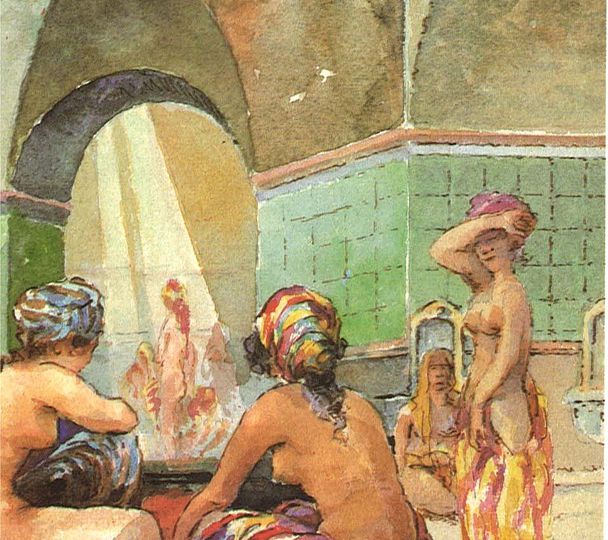

This brings me to the awesomely exhilarating and empowering experience I had at a Turkish hamam in Istanbul, Turkey. A ‘hamam’ is a traditional Turkish public bath that dates back to the 10th century and continues to exist as a modern variant in many countries from Turkey and Egypt to Hungary and Cyprus. With different spaces for men and women, a hamam was also used as a space for entertainment and celebration, where women sang and danced before weddings, births and other festive occasions.

My best friend and I had many discussions about visiting a hamam. With the socio-cultural baggage around female body issues and nudity overriding our desire to celebrate liberated femininity, we had just about given up on getting naked in Istanbul when we were literally dragged to one, unconsciously, by our tired feet, aching backs and stiff necks. Wrapped in a pestemal, a towel-like cotton covering to wrap our bare bodies, we took deep breaths and entered the unknown. ‘It should be okay if we just have the towels wrapped around us, they won’t yank them away from us, right?’ Turns out, they do. Though, before ‘they’ could, the realization of being weird, ‘covered’ anomalies in a space that was occupied by naked women of all ages and shapes and sizes made us uncover with a flourish and soak in the sauna heat, bonding with other women over, at first, timid glances, and later, bold laughter. Nakedness is always used by the corporate media, the violent state and patriarchal society as rendering an extreme degree of vulnerability on the ‘naked’ body, be it the act of stripping of prisoners or the stripping and parading of a naked Dalit woman through her village. While I would in no way compare the experiences between my privilege and the subordination of those oppressed by the State and its institutions, I could not help but wonder, that in a steamy room in an Istanbul by-lane, nakedness was an expression of feeling empowered, of a shared sense of community and an aesthetic appreciation for the female body, with its enormous love handles, and soft protruding tummies and flapping breasts, which was as beautiful and ‘real’ as the world outside said it was not.

While Dove emphasised the need to be ‘beautiful’ and the social acceptance it offers one, my experience in Istanbul was a much-needed reminder that not only was I much more than just an adjective, but also that the simpler joys of female companionship and uninhibited laughter should always take precedence over any materialistic, socially dictated, corporate driven propaganda.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।