The famous Pakistani poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, in his poem, Don’t Ask Me for That Love Again (1996, 395), powerfully articulates the dilemma between love and justice. Faiz begins by describing his beloved in the sublime language of love poetry:

“A glimpse of your face was evidence of springtime.

The sky, whenever I looked, was nothing but your eyes.

If you’d fall into my arms fate would be helpless.”

This creation of a private utopia composed of the beloved and him is, however, insistently challenged by the world outside. As the poet put it:

“As I went into alleys and in open markets

Saw bodies plastered with ash, bathed in blood.

I saw them sold and bought, again and again.

This too deserves attention.”

On an almost wistful painful note he concludes:

“There are other sorrows in this world,

Comforts other than love.

Don’t ask me, my love, for that love again.”

Faiz is a great lyric poet who sings of the love of the beloved which is nothing less than an exuberant celebration of all that makes life worth living in its plenitude. Yet the love of the beloved always has to struggle with another love.

Though lovers often live in their version of paradise cut off from the wider world, as far as Faiz is concerned, the world of suffering humanity intrudes. This world will intrude because at the end of the day romantic love is only one of the bonds which makes us human. Eros has to also compete with the human desire for politics or the desire to achieve the human good. What also makes us human is our empathy and concern for those outside the charmed circle of lovers.

Faiz articulates the notion of a love which transcends the love of a single person. Faiz is clear that the beauty of the beloved is undimmed, but is equally clear that in his heart there is another passion which he must follow.

How does this play out in queer lives? This tension between an intense and deeply personal love and a love which is wider in its embrace? If we go back to the queer archive, there is one remarkable figure who is able to take forward a notion of love which is both deeply personal and has a larger political dimension, and resolves the contradiction which Faiz poses. The love of the beloved coexists and feeds the love of justice. The figure who embodies this form of a personal love combined with a larger empathy is Edward Carpenter.

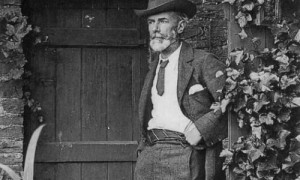

Edward Carpenter (1844-1929) was a fascinating figure from the history of English radicalism who embodied multiple forms of activism in the course of his life. He began as a socialist and worked closely with the trade union movement on improving the appalling conditions of the working class. He is today credited with being one of the inspirations for the founding of the British Labour party. He, however, did not restrict himself to socialism and went on to embrace a range of causes such as women’s suffrage, prisoners’ rights and animal rights.

Added to this really concrete engagement with bread-and-butter issues was a mystical side to Carpenter’s personality wherein he took to farming and leading a life close to nature. In his later life he moved into a farm which he called Millthorpe, and wrote on the connections between human beings and nature.

Carpenter was also an early internationalist who took a pacifist position against the First World War and was an early supporter of the anti-colonial struggle against imperialism. In his critique of modern civilisation he prefigured Gandhi by authoring Civilization – Its Cause and Cure which Gandhi in fact cites in Hind Swaraj.

Apart from this range of concerns, Carpenter was also an early advocate for homosexual rights. The era post the conviction of Irish queer writer Oscar Wilde was not a propitious one for the discussion of homosexual rights. But Carpenter wrote extensively on homosexuality and also lived an open life as a homosexual. On his farm, Millthorpe, he lived with George Merrill, a working class man, in a relationship which cut across class.

Carpenter’s life in Millthorpe proved to be a lodestar of what was possible even in the repressive England of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As Sheila Rowbothom put it, “To a new generation, the two men’s life at Millthorpe assumed mystical qualities of cross-class comradeship, ascetic self-sufficiency and utopian communal life … Carpenter and Merrill (were made) into cultural heroes, the exemplars of a free union which transcended the grim externals of everyday codes and laws.”[1]

Carpenter’s sexuality connected with his work in a seamless whole. Leela Gandhi, in her fascinating text, Affective Communities, draws a linkage between those who were seen as cranks or outcastes in the heart of empire, and the very beginnings of the anti-colonial movement. In particular, she draws our attention to the fin-de-siècle utopian socialism practised by figures such as Edward Carpenter, and their embodiment of “homosexuality as a capacity for radical kinship.”

What is remarkable about the unique kind of politics practised by Carpenter is that it was “marked by an apparent disregard for what we now know as ‘identity’ or ‘single issue politics’,” thus enabling the “easily transferable sympathies and promiscuous alliances that we have witnessed among unlikely ideological bedfellows.”[2]

What accounted for the remarkable range of Carpenter’s affinities? In Leela Gandhi’s opinion, Carpenter “stubbornly extols the experience and condition of homosexuality as the cornucopian source of his ethical and political capacity as the privileged rehearsal ground for his strange affinities with foreigners, outcastes, outsiders.”[3] Carpenter played a part in “expanding, however briefly, the ideological scope of modern homosexuality”.[4]

Carpenter’s life and politics is a remarkable pointer towards a form of queer politics wherein one moves beyond focussing on a single issue. While LGBT politics today is focused more narrowly than Carpenter’s expansive vision, the time for that form of identity politics may well have run out.

What outlines the urgent need to re-think our political vision is the triumph, in the U.S. presidential elections, of Donald Trump who will now preside over a world order of authoritarian leaders in countries as diverse as Russia, Syria, China, India, Philippines, Egypt and Turkey. In this more authoritarian world where all rights are under threat, the call for a larger political vision is compelling.

As Benjamin Franklin put it pithily, “If we do not hang together, we shall surely hang separately.”

Contemporary queer politics has something to learn from the remarkable life of Edward Carpenter. The only way to respond to the advent of a singularly more authoritarian era is to build an intersectional political vision which is broader and wider than LGBT politics. If one is committed to safeguarding rights in the new authoritarian era, one will have to tackle head-on the issue of socio-economic inequality, marginalisation on grounds of caste, and the numerous environmental struggles, all of which are asserting the norm that another world is possible.

[1] Sheila Rowbotham, Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love. London: Verso, 2008. p. 261.

[2] Leela Gandhi, Affective Communities. Delhi: Permanent Black, 2006. p. 177.

[3] Ibid. p. 35.

[4] Ibid. p. 35.

Cover image by Valentina Quiñonez, and courtesy of Margins Magazine.