In the first week of July, I travelled together with my partner (commonly known as ‘the DisObedient PA (DOPA)’ amongst family and friends) to Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi to meet up with a group of fellow sexuality, gender and disability rights activists. As a group, we had been discussing online for 2 years what might be achieved by establishing an African Coalition on Disability, Gender, Sexuality and Rights. So it was a very excited collection of people that gathered together for a three-day meeting to work out where we were going to next and who might join us on the journey.

Welcome

Stella Nkhonya, who is Director of Malawi Human Rights for Women and Girls with Disabilities in Lilongwe, together with Fatima Kalima a close friend from Blantyre who also runs Forum for the development of youth with disability had undertaken all the hard work of bringing of us together. Stella met me and the DOPA at the airport, together with her partner Steve, and piled us, our cases, my wheelchair, her crutches and all into her small adapted car and delivered us to the hotel to sleep off the journey.

Gathering for the start of our meeting the following morning, we were welcomed by a wonderful group of women from Malawi, including members and co-workers from Stella’s organisation, local gender and disability activists, our facilitator Lucresia Kuchande, a member of the National AIDS Commission of Malawi and Rachel Kachaje, Malawian ex-Government Minister of Disability and both a Deputy Chair of Disabled People International (DPI) and the 1st woman elected Chair of Southern African Federation of the Disabled Persons (SAFOD). From her perspective as ex-Minister, Rachel had seen few disabled women involved in politics and she argued that the Coalition needs to build its numbers, especially of women members and thus its power, to ensure that the voices of DW are strengthened and made audible. Some years back, she created Disabled Women in Africa (DIWA) for this very reason, providing a base from which to run training programmes that address disability and gender concerns.

Clearly focused on outcomes, Rachel advocated that for future Coalition action, her other priorities would lie in: undertaking a Needs Assessment amongst disabled people in South and East Africa; capacity building amongst disabled women and girls to improve their lobbying and advocacy skills; to strengthen Coalition links and advocacy to the UN Convention on Rights for Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and through these routes, to build a network of strong Disabled Women Human Rights Defenders and thus of disabled people’s organisations (DPOs).

Introducing ourselves

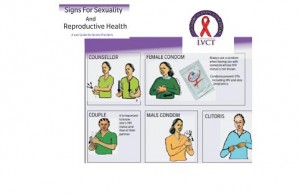

Although most of us had been chatting online for some time, we provided more detailed introductions including the relevance of our own work to sexuality gender and disability, which revealed some novel ideas. Washington Opiyo who had previously worked at LVCT Health in Kenya had at his fingertips, literally, an extensive and graphic collection of sexual Signs, many newly developed by the service that enabled workers to discuss and counsel deaf clients about HIV and AIDS, sexual health and relationships. This is crucial work as research has shown that in many countries deaf people (alongside other groups of disabled people) have higher rates of HIV infection. And deaf people in particular are a group who miss out on standard sexual health education, not only failing to hear the messages but being ignored by educators who regard deaf people as low or no risk.

by Opiyo, Washington, delivered at CREA- run Disability Sexuality & Rights Online Institute (DSROI), 2011 & 2013

I was really happy to meet Fatima at long last, as she and I had worked together on an online course on DSROI in 2013, run by CREA. Her introduction to her work provided us all with a stark depiction of the hard reality of disabled girls’ experiences whilst growing up locally. She spoke of the poverty that most face, of neglect in the home and unequal distribution of food and clothes, of the lack of marriage opportunities and, frequently, the loss of custody of any children they may bear. A pervasive factor throughout all of this is disabled girls’ vulnerability to violence, not only physical violence but also emotional, economic and sexual.

Non-disabled women face violence, but Fatima identified the different ways in which violence affects disabled women who may face frequent abuse from strangers, neighbors and even family members. Caregivers may refuse to give drugs and even support to use the toilet. Along with stigma and prejudice, WWDs face physical and sexual violence and rape, broadly thought to be at a higher rate than amongst non-disabled women. For example, in Zimbabwe, ‘a study in 2004 showed that 87.4 percent of girls with disabilities had been sexually abused; among them, 52.4 percent tested HIV positive’[1], whilst in Uganda, one-third of WWD told Human Rights Watch of sexual/physical violence with figures suggesting that the proportion might be as high as 7 in10.[2] The numbers may be higher yet when contexts such as the DRC and other war torn areas are considered.

The rationale for the higher levels of sexual violence directed at disabled women bears comparison with that faced by lesbians in somewhere like South Africa. We talked of how these different groups are deemed to have never experienced what it is to be a true woman, …to have had sex with a ‘real man’. And so they must be shown – by force if necessary – through what is known as ‘corrective’ rape. The attacks are based on these women’s deviations from heteronormative notions of how women should be.

The use of force and failure to advocate for civil and sexual rights has formed a constant undercurrent to Sian Maseko’s work as a sexual rights advocate and human rights defender in Zimbabwe. She too addressed how the struggle for sexual and disability rights merge together to form a common feminist thread when she shared stories of her work in a psychiatric hospital. Women here, diagnosed with schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, post partum depression were particularly vulnerable as, once given a psychiatric label, they found all societal and civil rights were denied them. They face violence and rape, are given long term contraception, are sterilised. One part of the challenge is that women who are hospitalised in the psychiatric hospital are thought to lack the capacity for consent to treatment or the ability to give consensual agreement to sex. And the multiple myths around sexuality held by hospital staff and even by the women themselves ease the path to sexual abuse and the perpetuation of the high levels of vulnerability of experienced by women with psychosocial (mental health) disabilities.

Yet women such a Stella and Ruth Acheinegeh, both disabled by polio when young, give the lie to the belief that there are no alternatives for disabled women in Africa. Stella was supported through school by her father, a teacher who believed that education was her route to a life beyond discrimination and stereotyping, although she did marry after college. Ruth had to fight different battles, with little support for education from her family and little encouragement for a marriage. Now, she runs a stall in the local market to maintain herself and other family members. The income of a disabled woman, if ‘unencumbered’ by a family, is viewed as joint familial wealth to be shared by all, unlike the money earned by brothers, for example, who have full personal control over any money they bring in. In addition, Ruth is part of North West Association of Youth with Disabilities and is involved in raising awareness, and challenging stigma within the community, supporting disabled young people to stay on at school and to build skills.

Stella spoke of other familial challenges to marriage locally, the interference of female relatives who, rather than being supportive, work in opposition to disabled young women’s wedding. Many believe the myths about the danger presented by a disabled girl to her matrilineal family if she marries, and to challenge this can split families. There are also prejudices about the danger posed by a DW’s children against the family, a myth propagated by some of the many churches. In light of the discouragement of marriage for young DW, Ruth, Stella and Fatima all know of the importance of income generation to encourage not only financial independence but also to create literacy and encourage sexual health education for disabled women, disabled girls and their parents. They have, between them, run a pig-rearing project, dress making/embroidery and savings schemes. Ruth was also key to the conduct of research into the ‘Reproductive health experiences among women with physical disabilities in the Northwest Region of Cameroon’. Along with visiting Canadian academics, Lynn Cockburn and Kimberly Bremer, she helped collect and analyse data and write up the results into a published paper[3].

Sharing our stories served an important role in helping us get to know each other better. And then Rachel, a woman with a steely focus and determination – she once struggled across a flooded river on an unstable tree trunk to reach school when a disabled girl, realising that education was her only route to a future – reminded us of the need to focus on practical outcomes from the meeting.

The personal stories also served to provide us with a way of mapping the skills and knowledge we brought to the coalition. Lucresia facilitated our pinpointing key themes in our current work and the collaborations we are involved in. This helped us identify our wide ranging connections: from links with a varied set of UN agencies, through government initiatives and large-scale charitable ventures to localised and individual projects aimed at, for example, sexuality and sexual health (SH) training with LGBT disabled people, anti-violence work with disabled girls and women, and provision of HIV, AIDS and SRH services for disabled and non-disabled people alike.

[1] Kamga, Serges Alain Djoyou (Feb 2011) ‘The Rights of Women With Disabilities in Africa: Does the Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa Offer Any Hope?’ Centre for Women Policy Studies, p4

[2] Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘“As if We Weren’t Human” Discrimination and Violence against Women with Disabilities in Northern Uganda’, p12.

[3] Kimberly Bremer, Lynn Cockburn and Ruth Acheinegeh (2010) ‘Reproductive health experiences among women with physical disabilities in the Northwest Region of Cameroon’ International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 108 (2010) 211–213