I grew up with a book cupboard where Paul Gallico’s Love of Seven Dolls rubbed shoulders with Germain Greer’s The Female Eunuch. Paul Gallico was my grandmother’s favourite author. But she also read James Hadley Chase and Wilbur Smith with great joy. I read all the racy bits during long afternoons when she slept with a cloth tied around her eyes to keep out the light. I read like a mouse, quiet, feeling feelings that were unshareable. I never then wondered what on earth she was doing with these racy writers in the cupboard. She and her sisters taught themselves to read and write, and learnt English, standing hidden behind a curtain while a tutor came home to teach their brothers all the things boys learnt when receiving a formal education. She wanted me to grow up to be independent and earn a living in a world she saw was changing, where women could do and be things that she’d have liked to do and be.

One of her desires was to be a Hollywood actress opposite Yul Brynner. She thought he was hot, but she didn’t use the word. She called him handsome.

—

There was the old, old lady I met as she lay in dismal poverty with a life that experienced acting in cinema in Assam at a time when it was out of bounds to women. She was Assam’s first woman actor, her name was Aideo Handique. She acted in Assam’s first film, Joymoti. In the film, the actress called her co-actor ‘bongohordeo’, ‘dear husband’. She was ostracized. Never acted again. Remained unmarried. I met her in October 2002, just before she died. She looked like anybody’s grandmother and she was nobody’s grandmother.

—

For years, men played the role of women, onstage and onscreen. Some of those men were as hot as women. A thing society didn’t want women to be. Hot. Or perhaps society did. Because society has always loved scandal, gossip and hot things. It is families that don’t want their women to provide that hot stuff. Their women, please note. And by families I don’t mean the ones that swim upstream with unmarried, divorced, many times married, single parent, gender bending and child adopting persons. By families I mean father-mother-husband-wife-son-daughter-siblings-and-in-laws, representing the foundations of ‘respectable’ society.

My grandmother also told me that after I had become independent, I should marry a lumberjack. Independence for her was a big thing, denied, to women she knew and to the woman she was, because of their being born female. Independence meant earning. Marrying a lumberjack represented the power to choose your life, another kind of independence, denied. Being born female meant not earning, not choosing your life, and power and independence denied. This has been the life experience of generations of women going back thousands of years before her, in different parts of the world, across cultures. This is still the life experience of many today, but not as many as in times past. The feminist has something to do with this change. The feminist made the connection between rights and sexuality and made this connection visible.

3,500-odd years ago, Queen Hatshepsut ruled in Egypt for twenty years dressed as a man. She wore a beard too. This was the garb of male authority and she had to assume it to assume power.

1,500 years ago, Greek historian Herodotus noted the difference in status between Egyptian and Greek women; the great majority of the latter conducted their lives within the narrow confines of domestic responsibility, a role determined by the norms and rules of an ancient and patriarchal view of sexuality. Egyptian women led their lives with greater freedom across domestic as well as economic and business spheres. There was pay parity between the genders. This is more than you can say for great parts of the world today.

A hundred odd years ago, somewhere in the early decades of the previous century, African feminists led by Funmilayo Anikulapo-Kuti sang a song of protest against the injustices of their ruler. They sang, “Alake, for a long time you have used your penis as a mark of authority that you are our husband. Today we shall reverse the order and use our vagina to play the role of husband.”

Alake means ‘king’. I think this ruler was forced, finally, to step down.

What is feminism? Shanzeh Khurram says, “Feminists can be sex positive or anti-pornography. Feminists can be straight, bisexual, pansexual, asexual or gay. Feminists can also be men, since any person – male or female – who wants equal opportunities for both sexes is a feminist.” In her easy-to-read, clear and well-written piece, she goes on to say, “And while some radical feminists are transphobic, feminism in its true sense is pro-trans. Transfeminism is a prominent branch of third wave feminism which views gender as fluid and not being determined solely by biology.”

What is sexuality? Sexuality is many things to do with life and living, the way we see ourselves and the way we see and treat people around us. It is about sex, yes; and about sexual activities, biological sex, gender, gender roles, and socio-cultural perceptions of all of this. We don’t quite know everything that sexuality is, but we know that it plays a key part in just about everything.

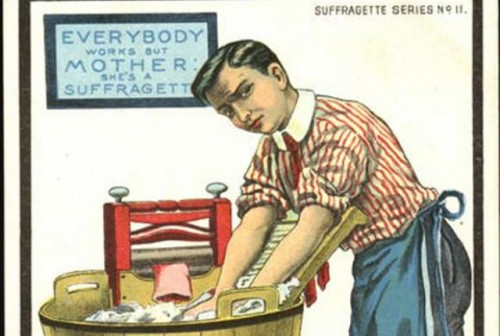

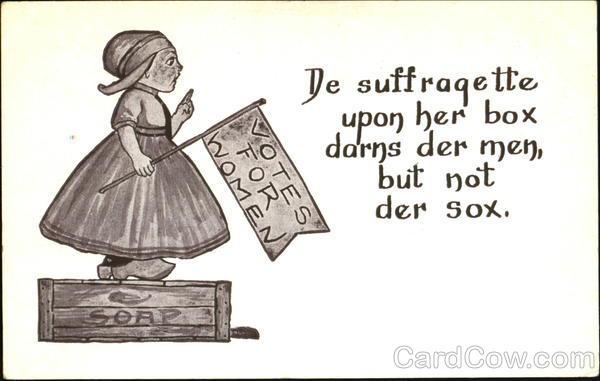

Take the right to vote, for instance. Why shouldn’t women have it? 19th century British novelist Mary Augusta Ward in An Appeal Against Female Suffrage said that “the necessary and normal experience of women does not and can never provide them with such materials for sound judgement as are open to men”. Anti-suffragette cartoons of the time explain things quite clearly: putting the good woman in her place, and the suffragette on a soapbox or the witch’s dunking chair.

This business of women and socks, it has travelled through the centuries. In my article of last month, I referred to a pet peeve of mine, a Kellogg’s ad where a woman who doesn’t get enough fibre in her diet is unable to be good-humoured when helping her husband find his socks. Post-Kellogg’s, she smiles and plays ball with those washed socks; the perfect wife.

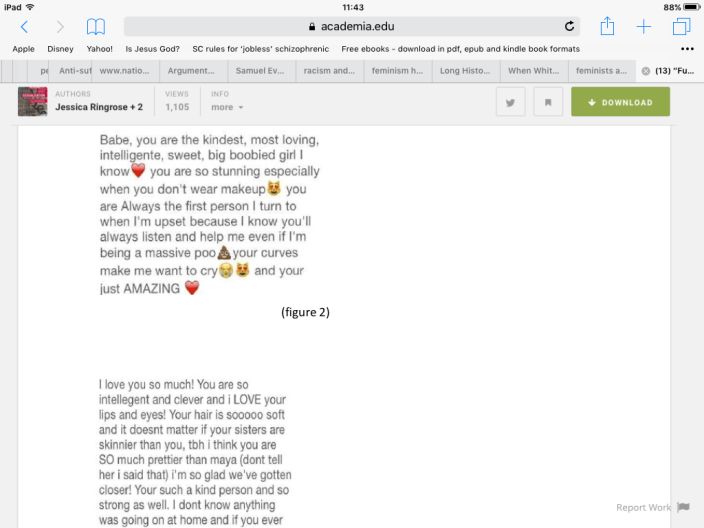

Lacey, Katie, Catrin, Tori and Ruby are youngsters who were part of a research and study of post-feminism, and fourth wave social media feminism, that involved their participation as teen girls in a theatre school. Somewhere during the course of their participation, they decided of their own volition to send each other personal messages using social media platforms, messages that acknowledged each other as friends, as a peer support system, and as young girls ready to trash what may be referred to as the marketisation of their lives to achieve the goal of desirability to men. I love what they wrote to each other, these girls so very much younger than I am. So I took a screenshot of the paper I was reading (three cheers for digital technology!) and am sharing it here.

You can read the paper by Jessica Ringrose and her co-authors at “Fuck Your Body Image”: Teen Girls, Twitter and Instagram Feminism In and Around School.

On July 6, 2014, The Anonymous Writer posted a long piece on Facebook titled Feminism Redefined which she ended with, “My name is Pramitha & I am not a feminist.” Clearly, she is not. There is a lot I find frightening at multiple levels about the thoughts shared in this piece. Fourth wave social media feminism must be encouraged. The job isn’t done if someone believes, “We need to understand the psychology of rapists in order to understand why it takes place. Men don’t turn into misogynists by themselves. It takes a woman to turn a man into a misogynist. Women should be extremely careful while dealing with men, especially if they’re in love with you. Insulting them & making them feel unworthy of your love might turn their love into hatred; & then there is no telling what he might do.” I do not particularly wish to ask whether she has an explanation for physical and sexual violence perpetrated upon men. The world’s first centre for male victims of rape and sexual violence has been opened in Sweden. I look for a link to feminism because in my gut I know there is one. Perhaps it is that sexuality is closely linked to concepts of power, entitlement and vulnerability. Conventional and stereotypical views of vulnerability tend to see men as a sort of entitled masculine invulnerable. To see male vulnerability in the context of sexuality, men excluded from the club of the masculine invulnerable, is turning things around, borrowing a lens from the feminist’s toolkit.

There is one thing that is clear to me. Wherever feminism has focused a lens upon attitudes, behaviours, events and systems, it has revealed that the underlying issues causing discrimination and violating human rights are deeply entwined with issues of sexuality. Every aspect of life and human rights that any feminist of any label has advocated or fought for is intricately linked to sexuality.

Cover image courtesy: Card Cow Vintage Postcards