When the opportunity to work on a documentary film shoot about mapping Ramleela (a dramatic folk re-enactment of the life of Ram(a), an avatar of Hindu god Vishnu, and his wife Sita, an avatar of goddess Lakshmi) performance traditions across the state of Orissa presented itself, I had three thoughts in my head. One: I will get to visit places that will never be on any tourist’s itinerary. Two: I will get a chance to expand my perception of Orissa beyond Kandhamal (riots) & POSCO (people’s resistance). Three: I will finally learn the story of the Ramayana.

After a few hours of reading Wikipedia’s page on the Ramayana, watching different film versions of the story, and watching a film about the different versions of the story, I felt prepared enough to jump in. Who was I kidding?

My limited language skills (English and Hindi only) were going to be an obvious obstacle. Being the spoilt city girl that I am, I also wondered if I would have access to Western toilets, phone network, television, and air conditioning, in this exact order of priority. Irrespective, I had already signed up. The delicious idea of new experiences waiting to enrich my life, and the general excitement of the unknown, had blurred my vision to any rational apprehensions.

The moment when I am about to step into an airplane and fly across hundreds of miles within minutes – this moment excites me no end. Standing on a railway platform gives me a thrill like no other. The movement across space and time zones feels like I am defying nature, fighting it, and winning every time I arrive safely.

And there I was in no time, hanging out at a café in Bhubaneshwar, waiting to meet the team. From that day, for the next twenty, with my crew of six men, living out of a suitcase, shooting all night every night, watching the story of Ram and Sita unfold in an unfamiliar language, sleeping for barely three hours at a stretch during the days between long car rides on highways that cut across the most magnificent landscapes I had ever seen in India, Orissa was breathtaking. It truly was. The tribal settlements and villages, thick forest covers, the hillocks, and the wide-open skies made me want to pitch a tent and stay.

It dawned on me early on how seriously the Oriya people take their Ramleela traditions. On our first evening in a town called Boudh in central Orissa, we saw oil lamps lit outside every house to welcome the birth of Ram, which was to be the first episodic performance that night. This sort of involvement of the audience in the performance was one of the most fascinating aspects of my trip.

The best example would be of the time we were documenting the episode of Ram and Sita’s wedding in a quaint little village called Debgarh, about a 30-minute drive from Boudh. Once the wedding took place, all the other characters on stage walked over to Ram and Sita for their blessings. Just then, some of the audience members began climbing on to the stage, followed by many more. It took me a moment to realise what was happening. The villagers also wanted to make offerings and receive blessings, since they believed that the two male actors on stage playing the characters of Ram and Sita were truly their Lord Ram and Sita Maa (Mother). Call it blind faith or a complete suspension of disbelief, the residents of village Debgarh in Orissa had become, for that one night and many more nights to come, subjects of the kingdom of Ayodhya.

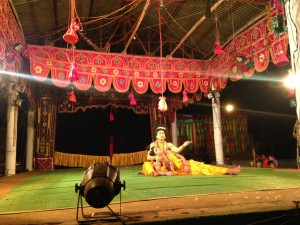

To be able to create such a spectacle with this level of believability year after year with an all-male cast, the actors themselves have to go through a transformation process. They are chosen primarily on the basis of their ability to memorise dialogues. Men with ‘feminine’ facial features are preferred for female roles. Once selected, they are expected to move in to the temple compound a month before the performances begin, adopt Brahmacharya-hood (a traditional way of living for students learning from a guru), which essentially means a celibate life, one (vegetarian) meal a day, and spending evenings rehearsing for the performance. The music, songs and various kinds of handmade firecrackers bring drama to the story, while the ‘face painting’ (make-up) and costumes add the final touches to the spectacle.

My first night in the green room was absolutely surreal. I saw men busy stuffing their brassieres, putting on long wigs, and wearing saris. Paint bottles and paintbrushes covered a table where an older man was busy painting a young man’s face with immense concentration. I had been told to be very careful about not touching any of the actors, since that would break their vow of celibacy.

So there I stood amongst the chaos of men rushing to get ready for the performance under a small tent behind the stage, trying hard not to move, but completely absorbed by the novelty of what I was witnessing. As my all-male crew moved around easily and excitedly to catch all the action, I found myself dodging the crowd like I was in a Mission Impossible sequence avoiding high-security laser beams. Even a slight brush against an actor’s costume might have triggered an alarm. As the nights went by, it seemed that the actors were not as concerned about my presence as I had been made to believe. Or maybe I was just excused since I was clearly an outsider.

Despite my alien appearance and behaviour, I was expected to uphold certain religious beliefs. One night, I was told very seriously by the Ramleela coordinator to make sure I tie my hair the next night. The episode was going to involve goddess Durga, and they believed that women with untied hair on that night could be possessed by evil. Even though I wasn’t thrilled about being told how to wear my hair, and that too for a reason that made no sense to me, I agreed to do it because I didn’t want to offend him. Faith is faith after all, something that you cannot argue or even reason with, and Orissa, I realised, was at a whole different level of faith.

The novelty of these beliefs, festivals and ways of life had now started wearing off for me. I felt quite claustrophobic. It wasn’t helping that I was constantly connected to the world through my phone, browsing through photographs from a friend who had just moved to Canada, and from friends in Delhi, reminding me about what I had left behind. I felt like I was in some time warp, and I was desperately fighting to get out and return to the world I knew. Orissa had tested my limits of ‘tolerance’. I was completely outside my comfort zone. But isn’t that the purpose of travel?

I believe that travel is meant to make you seek the new, and meet the ‘Other’. In times such as ours, it is important that we put ourselves through such experiences and learn to respect those who are different from us. The magic happens when, even in the differences, we find common ground.

I will never forget how in Debgarh village, where most of the audience were tribal people and would walk many kilometres to attend the performance each night, three women offered me a spot on their straw mat. They must have noticed me squatting near the camera. It was only once I sat down with them that I saw their faces clearly. I had never seen more beautiful women in my life! We exchanged smiles, and they talked amongst themselves for a while looking at me. Our glaring differences made me assume there was nothing I could talk to them about; and even if I did, what language would I use? Finally, one of the women asked me with a mix of hand gestures and words – “Roti (bread) or rice?” I almost jumped with excitement at having understood the question! With a big smile and the same hand gestures I told them, “I eat both.”

It took me some time to realise what this almost insignificant piece of conversation had really meant. Those women had successfully managed to communicate with me, and identify something that we could each relate to. That little interaction had made me feel more connected to the people of Orissa than anything else. That, and the many sunrises I witnessed at the end of every night’s shoot. That is where the magic of travel truly lies.