I am a non-binary person assigned female at birth, currently living in Bombay. I dress in a manner which is seen as stereotypically male, in shirts, t-shirts, pants and shorts with “men’s” footwear. My hair is short, I’m dark-skinned, and my breasts are, more often than not, not perceivable, which is how I prefer it. I think I appear androgynous but apparently am perceived to be a man by most people. You will understand why I’m giving this description here up front as you read on.

Before we talk about public spaces and sexuality, I would like to take a step back and speak about public spaces and gender. We all know the position of women in a public space, the kind of issues and harassment faced by women on the streets, in public transport, in taxis and autos, malls and shops, restaurants etc. We also know about spaces which for the most part are seen as safe spaces for women: the women’s compartment in the metro and trains, women’s bathrooms, women’s waiting rooms, feminist conferences and gatherings, and even the streets during the day time. These spaces may not be safe all the time, but the general perception is that these are safer than many others, especially before sunset. But the solution to making a space safe for women seems to be to have spaces with “Women Only” plastered in pink, like in metro stations. Or the familiar image of a fair-skinned woman with her saree palloo draped chastely around her head on women compartments in Bombay’s local trains.

Bombay local: Icon outside women’s compartments on Mumbai suburban trains.

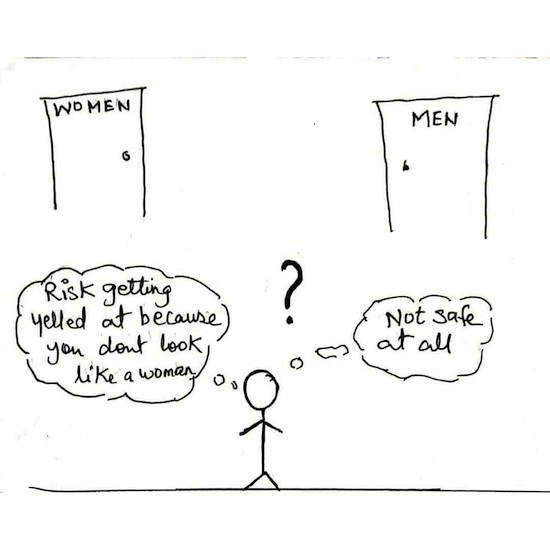

Creating safe spaces by gendering them will work only for those who fall within the binary of woman or man. So what happens to all those who are in between and beyond the binary in the public space?

Up until two years ago, I had long hair. Apparently, that was sufficient for me to qualify as a woman. Since I have started to actively identify as non-binary and appear non-binary, my relationship with public spaces has changed drastically, even, and sometimes especially, in the spaces which are deemed safe for women. In the past two years, I have been told to go to the men’s bathroom, the men’s security check lines at airports, malls, and theatres, and to the men’s changing room, numerous times. I usually ignore the instructions or correct them if needed and head to the women’s lines (because where else will I go?). Last year, at the Delhi domestic airport, I stood in the women’s security check line. The female security guard said that it’s the women’s line. I replied that I know and that I’m a woman, and walked into that little cabin where they do the checking. She then asked, “Kya aap pakka aurat ho?” (Are you sure you’re a woman?) as if my answer would change, and then proceeded to run the metal detector particularly hard against my breasts. I was shocked and then angry. I asked for the superior officer and proceeded to file a complaint against her for harassment. If a male security office cannot do that to me, why should it be okay for a female security officer to do so? As expected, the complaint didn’t go anywhere.

Public bathrooms have become a source of great anxiety for me, especially when there are bathroom attendants. In the past two and a half months, I have been physically assaulted seven times in women’s bathrooms with women putting their hands on my chest and attempting to push me out. This was done both by the bathroom attendants as well as by the others who were using the bathroom. Two weeks ago, at a bank, a woman grabbed me by my arm, dragged me out of the bathroom, and demanded to see my ID card. She was just another customer at the bank. It’s come to a point where I don’t drink water when I’m outside simply so that I can avoid using the bathroom.

Art by Mx. Dan Rebello

I’m lucky to be working with a feminist non-profit which is very queer friendly, and with colleagues who support me. But not all the places that I go to in the line of work are necessarily safe for me. Misgendering at feminist conferences by women and sometimes other queer and trans persons is a common occurrence that actually personally does not bother me because I don’t care particularly about how others perceive me and it doesn’t trigger me. (This is not universal by any measure. Different queer and trans persons may use and want others to use pronouns which they identify with.) But there are also a lot of said and unsaid demands on me to tell people which pronoun I go by so that others can be politically correct. There’s been heckling at a few workshops where I was facilitating, and a LOT of people staring at my chest just to figure out which box I should be put in. What do I do when spaces that are supposed to be safe for women and queer persons become unsafe? I understand that many a time, women and girls who ask me whether I’m a man or woman are asking this from a place of curiosity and because they may not have met someone who looks like me. This is fine, and I’m okay with answering these questions. But where I should draw the line is something that I’m continuously asking myself.

Last year in July, I faced assault when taking an auto back at night in Bombay. I filed a complaint against the driver as I had booked the auto through an app. When the company investigated the allegation, one of the questions which they internally discussed was also if they were sure that I’m a woman after seeing some photos of me online. As if it is okay for a man to be assaulted. As if gender had any role at all to play here.

We have gendered public spaces so much in the name of safety that it’s become unsafe for a whole group of people, and these are the people who do not ‘pass’ as male or female, who are seen as ‘oddities’ in society.

Women only: “Women only” signage at Delhi metro stations

I am also very aware of a certain level of privilege that I hold as someone living in a metro city and as someone who speaks English, but the truth is that this privilege goes out of the window when someone threatens to or actually hurts me physically, simply because I wanted to pee.

And it only gets more complicated when you bring in sexuality. This one time, I was traveling in Rajasthan with a friend who I was then seeing, both of us “incorrectly female” in full glory. When we were walking around someplace, they said to me, “I thought people stared at me. But I realise now just how many more looks we are getting when we are both walking together.” And these stares were unfortunately the norm when we were out in public together, in Bombay, in Delhi, in malls, at the grocery store, at airports, in autos, the metro, local cinemas, or just the public bathroom. It’s easier when we are together or with friends and other queer persons, but it’s not easy.

As renowned queer scholar Judith Butler said, “For those who are still looking to become possible, possibility is a necessity.” This is essential but also easier said than done. When someone simply wants to live their life but is forced to confront what is already a difficult truth, day after day everywhere, one realises the necessity of being different and of living at a variance from established societal norms, not just for oneself but also for others who may also want to live similarly. This passes on courage and energy, silently yet out loud, at the same time. As the friend mentioned above said, after a Delhi metro security officer asked us to go to the men’s line: Hum jaise bahut milne waale hai. Seekh lo. You will be seeing many more like us. Get used to it.