In 2013, I enrolled for a Master’s degree to formally pursue my interest in English literature and cultural studies in a quaint little research space called the Central Institute for English and Foreign Languages in Hyderabad. Having only studied Mass Media thus far, I intended on auditing courses from other humanities departments, both to satiate my curiosity and meet due credit requirements in the two years of my programme. Among a range of exciting courses and foreign languages on offer, Professor Hoshang Merchant’s class on Gay Indian Literature not only stood out for the host of interesting prose and poetry advertised but it also happened to meet both of my criteria.

As a young woman interested mostly in modernist fiction and postmodern poetry thus far, I never had the inclination or awareness to explore queer fiction in the library or bookstores I frequented at the time (Crossword, Bahrisons and ancient Victorian libraries in Bombay that were unlikely to carry gay literature) and most books recommended to me would have no allusions to sex altogether, leave alone address homosexuality as more than in innuendo or insinuation. To be perfectly honest, as a straight woman, I didn’t consider queer literature as a genre to be explored beyond Anaïs Nin’s Delta of Venus which was about as far as my prudish self would set foot in any erotica. This also goes to show that in my limited understanding of gay literature, I imagined it to only concern a sexual context and hence be of no consequence to me.

Early in his teaching career, Hoshang Merchant had quite famously earned a reputation for rebuking the authorities in universities across the world which frequently led to his ‘controversial’ course being taken off the syllabus undeclared. Our small campus in the outskirts of Secunderabad was no anomaly and even before the semester began, rumours of him never making it to our campus were afloat. If such a situation were to arise, students were never offered much beyond a non-committal response from the authorities in a public issue notice passed under the guise of scheduling issues (but it was evident that it was very much the subject matter of his teachings and not a matter of his schedule that was the root cause).

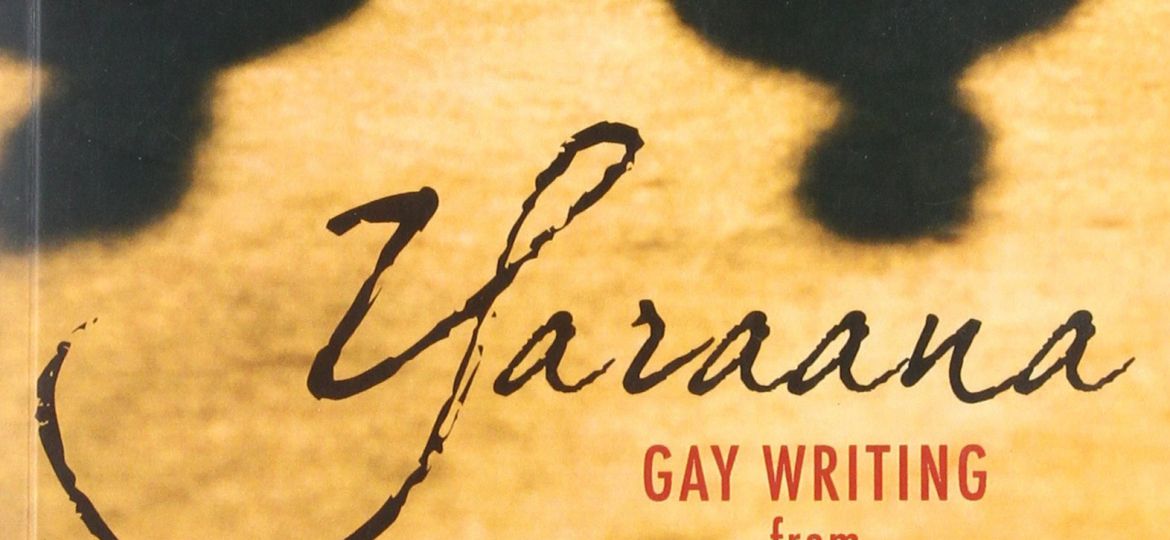

When his course was finally made available to us (after being plugged out of the literature programme in Hyderabad Central University), a bunch of curious students (mostly women) signed up for it. On the first day of class, twelve girls and two boys showed up to a rather empty classroom where a beautiful Parsi man with a long greying beard – poised like a wizard – sat delicately perched on the first bench beckoning us in. Professor Hoshang Merchant was easily one of the most qualified professors on campus – by degree, academic repertoire and teaching experience. Yet, he never took himself too seriously. By syllabus, he taught us his own book Yaarana. By anecdotes, he told us in explicit detail about his sexual adventures, also documented in some of his books. This soon led to the exit of any and all men from his classes, which had him equal parts sad and amused. As Hoshang (which he insisted we call him if we weren’t up to ‘Parsi fairy’) began to almost provoke us to think about literary classics from a homosexual perspective, he also began to tell us about his time in Purdue, Jerusalem, and Iran, and the different shades of the queer experience coloured by politics, war and religion in the 1970s across the world. For the uninitiated, the experience was often overwhelming. His poetry was as personal as his classes were. He told us about a complicated relationship with his sister, estranged lovers, the closeted gay men of Bollywood (which were the classes we looked forward to most) and the almost endemic homophobia and discrimination he had to navigate growing up in the iconic Parsi Colony in Bombay.

His personal narratives merged seamlessly with the texts written or taught by him. His poetic voice was so uncomfortably personal that it was hard for straight men to sit through class without showing their visible discomfort; the rest of us however valued the forced shift in perspective, one that an individual reading of most such texts would have never brought about without an external intervention.

From Ismat Chugtai’s Urdu short story Lihaaf to Vijay Tendulkar’s Marathi play Mitrachi Goshta on same-sex attraction, we studied a number of short works of fiction that were considered to be pathbreaking for their time but also threw their authors’ writing career into turmoil leading to legal persecution, obscenity trials and in some cases also an imminent threat to their lives.

In not just studying texts that are now widely accepted as mainstream ‘gay’ literature so to speak, but also deconstructing ancient Indian texts through a queer lens, there was always palpable tension in the classroom on being asked to examine and re-examine the Ramayana and the Mahabharata for elements of same-sex desire, which was almost always accompanied with shame for feeling so threatened by the notion of homosexuality in books of mythology that have historically been deemed to be holy and untouchable.

Through our discomfort, shame, and often stubborn refusal to rise above heteronormativity, we unpacked a lot of these negative emotions by critically analysing texts that were neither the Kamasutra nor discourses such as Foucault’s on sexuality. We learned to normalise a non-binary narrative in life through our old professor’s very young and vividly remembered adventures of self-discovery and academic trajectory.

As our we evolved to find physical and inter-personal comfort in our collective learning, we grew to accept the literary lives of those that were othered even in literature and grew in kinship with our professor who taught us acceptance of more than just gay poetry and prose.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।

Cover Photo: Amazon