This post is part of TARSHI’s #TalkSexuality campaign on Comprehensive Sexuality Education in collaboration with Youth Ki Awaaz. The author chose to remain anonymous.

Last year in August, my paternal grandfather (dada) passed away. I was shocked at the pure occurrence of this eventuality translating into a reality; an end, that all members of my family had been waiting for. In November 2013, I finally mustered the courage to pick up the phone and call the Delhi police to file an FIR against my dada; only to realise two things – first, how easy it actually was to make that call and second, how incapable and powerless the masculine Delhi police cops were that day. After narrating elaborate details of the years of sexual abuse and domestic violence, for close to two hours, all that the two policemen said was, “This is a case of domestic violence. We can see your grandfather is an arrogant stubborn man. But since this house belongs to him we cannot arrest him. You can lock him in his room and beat him up if you wish to.” On their way out, they looked dada in the eye, warned him to behave himself, and left. I was sure I wasn’t going to waste another ounce of my energy in finding ‘justice’. I called my friends to come pick me up, and I left.

I was in class seven when I saw my dada masturbating right next to the window in his room that faced our backyard, where my older cousin sister and I had gone to keep our plates after dinner; a practice all the girls of the thirteen member patriarchal joint family were socialised to do; a routine my dada had mandated in his quest for ‘perfect discipline’, and was hence accustomed to the routine of this routine. My sister, as if familiar to this sight, without even a slight sign of bewilderment, grabbed my hand and rushed me to our room. Later that night she told me that was called masturbating. I clearly remember not sharing this with my mother. But I can’t recollect why. I know I wasn’t scared of not being trusted, but I still hesitated.

The last time I saw my dada’s penis was when I was in eleventh grade. I was talking to a dear friend on the phone and Dada asked me to keep the phone down. When I refused to, he unzipped and charged towards me. Sitting on the couch, my face was at the level of his penis. Nobody ever talks about these grey areas of your life, there is no text while schooling that equips you with these life skills. The fear I felt in my entire body that day was the only telling moment of knowing that what was happening was wrong, and that I needed to do something, anything, to keep myself safe. Petrified, I narrated what was happening to my friend, and she asked me to go to my room and lock myself up. Wiping my tears and controlling my fears, I pushed him, screaming “aapko toh yahi karna aata hai” (you only know how to do this), and ran to my room. My dadi (paternal grandmother) instead of stopping her husband was stopping me from ‘reacting’. I remember sharing this incident with my mother when she got back from work, sitting on our traditional Gujarati jhoola (swing), outside in our garden. She believed me, but also didn’t want to believe me. I was getting angrier by the second at her absence of reaction, my expectation of at least being hugged. Later that day, the anger stemming from the morning of helplessness solidified into the deepest hidden truth of our family.

In our common kitchen, along with my mother, cousin sister and younger cousin brother, and their mother, I sat and heard the stories of how they have all been sexually abused by the head of the family – our dada. Domestic violence was a common event in our house. People screaming, shouting, abusing; mothers running with their children inside their rooms, my father protecting my mother and me from dada; all of these had made me, and I still am, hypersensitive to loud noise. It’s like the fear grips me all over again.

But sexual abuse that continued for 17 years, to eight members of a 13 member over-valued joint family, where none of the male members knew about it, was turning into the biggest question that shrouded my adolescent years. How is this possible? Why did we let it on? Why didn’t we say “No, enough is enough!”?

We often laughed about it collectively in the same kitchen, or while watching a movie – humour became a tool for us to live through this reality of our collective lives. We felt helpless and consequently, vehemently angry. The control he had on all of us – what we wear, what we eat, what we watch on TV. The fear that his authoritarian voice and piercingly ruthless eyes filled with sadistic pleasure cast on us, was neatly etched in our inner worlds. Crying together and comforting each other; knowing that this is what binds us together in spite of our irreparable differences, was the only way we coped and defended ourselves.

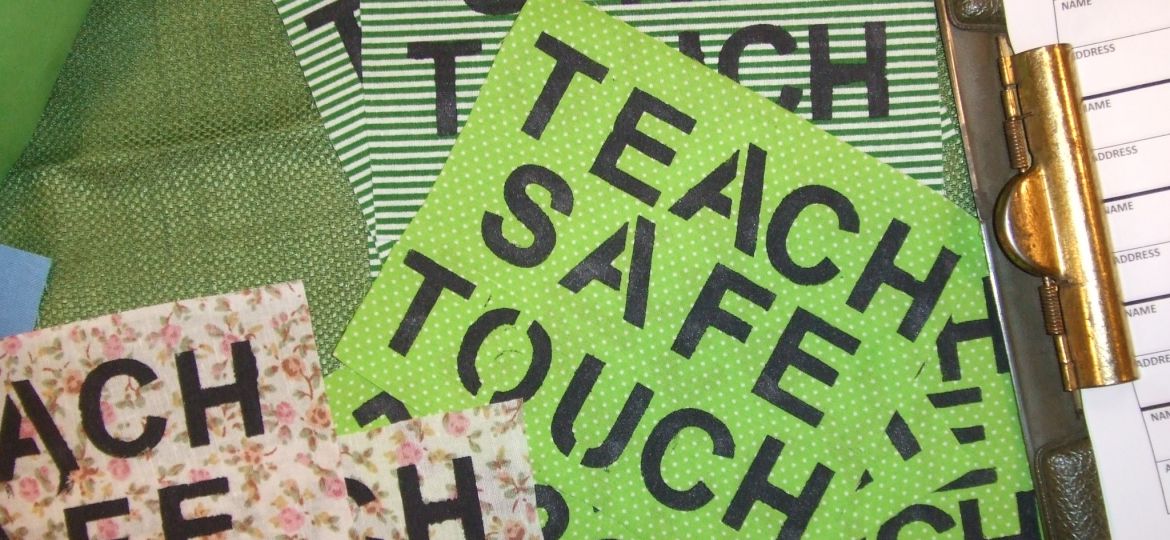

All my friends knew about the reality of my ‘family’. As my therapist once observed, “it’s like you are making an army of people who will support you…” And how they have supported me! We were all the same age; talking and sharing was the only way that I could find some healing. But how I wish I had someone, a Counsellor in school, or even a teacher to share this with, to help me, tell me the Do’s and Don’ts, talk about ‘Comfortable Feeling and Uncomfortable Feeling’, or say that I have a right to say no because it is my body!

I wrote my Masters dissertation on understanding my dada and why none of us neither confronted him nor made the unspoken truth known. With the help of my listening, supportive and critically analytical guides, I began to start unravelling and disentangling the threads that had tied me thus far. I gifted my dada a copy of it on his birthday. I made my father read it as well. It was because of the process behind writing my dissertation that I was able to confront him and call the cops, finally finding a closure to that chapter of my life; something I wish I had done eight years back, when my mother was still alive.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें